In contemporary religious discourse, ambiguity is often treated as a virtue. Spirituality is described in gradients, journeys, and evolving identities. Commitment is framed as fluid. Yet when one turns to the writings of the Apostle Paul, the tone shifts markedly. His letters, composed in the first century to emerging Christian assemblies, present humanity in sharply defined categories. According to his doctrine, a person stands in one of two spiritual conditions. The dividing line is not moral refinement, church affiliation, or ritual participation, but faith in the person and work of Christ.

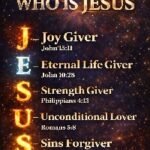

The statement frequently cited to summarize this divide appears in the Gospel of John: “He that believeth on the Son hath everlasting life.” Although the Fourth Gospel predates Paul’s epistles, the apostle’s letters articulate the theological implications of that claim with sustained precision. In Paul’s framework, belief establishes a definitive change in status. One is either united with Christ or remains outside that union. There is no intermediate state described in his doctrinal explanations.

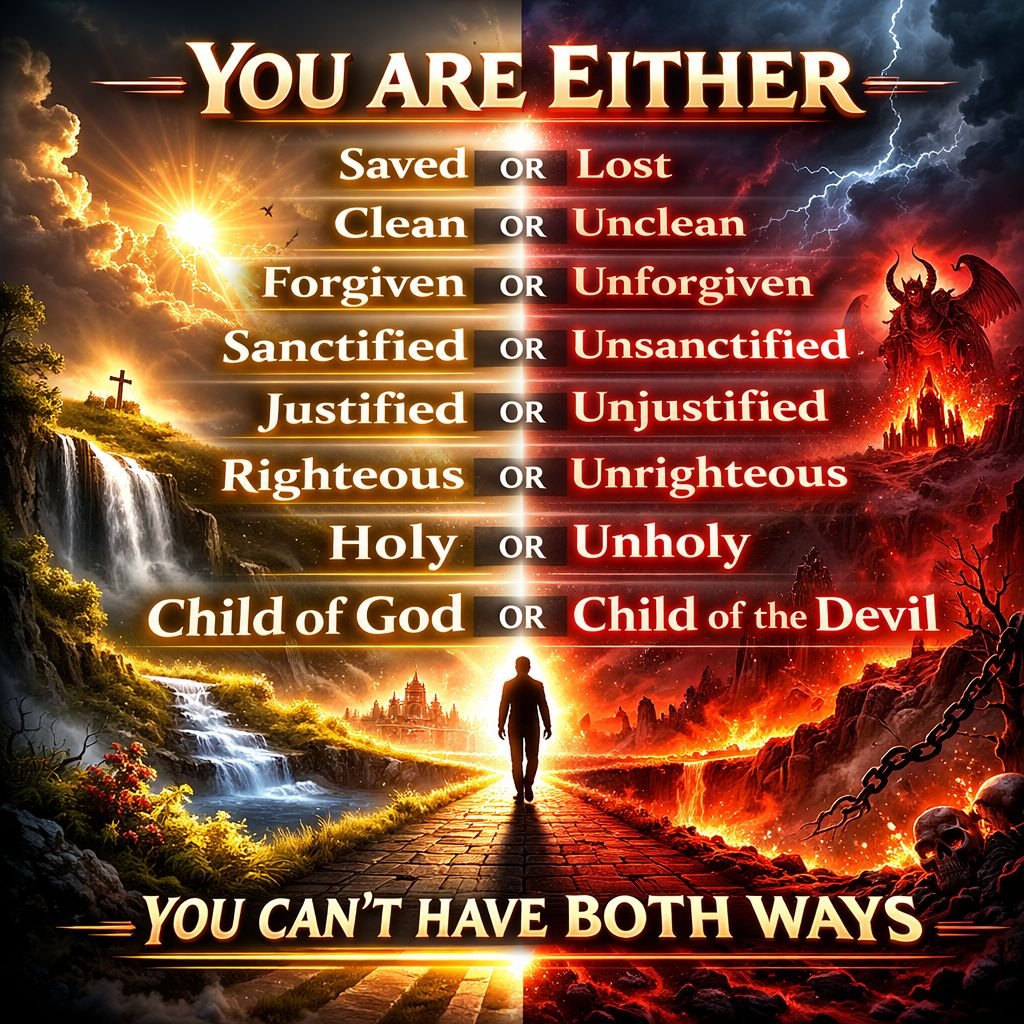

The clarity of this distinction can be traced through several of his central themes: justification, reconciliation, forgiveness, sanctification, and adoption. Each is presented as a completed act applied to the believer at the moment of faith. Conversely, those who do not believe are depicted as remaining under condemnation. The binary structure may appear stark to modern sensibilities, yet it is consistent across the Pauline corpus.

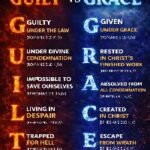

In the Epistle to the Ephesians 2:8–9, salvation is described as a gift received by grace through faith, explicitly “not of works.” The language is categorical. If salvation is by grace, it cannot simultaneously be by merit. The exclusion of works is not partial but absolute. Paul reinforces the point in the Epistle to the Romans 11:6, arguing that grace and works operate on mutually exclusive principles. If works contribute, grace ceases to be grace.

This theological framework leaves little room for hybrid models in which human performance supplements divine action. In Romans 3:24, believers are said to be “justified freely by his grace.” The term justified is judicial. It indicates a declaration rendered in a legal context. The verdict is not progressive but decisive. A person is either declared righteous or remains guilty.

Romans 8:1 extends the implication: “There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus.” The absence of condemnation is present tense and comprehensive. Paul does not describe degrees of condemnation for believers, nor does he portray justification as provisional. The believer’s status is settled because it rests on Christ’s completed work.

The contrast between those “in Christ” and those “in Adam” further sharpens the distinction. In Romans 5, Paul traces humanity’s predicament to Adam’s disobedience, through which sin and death entered the world. He then juxtaposes Adam with Christ, whose obedience brings justification and life. The structure is representational. Every person belongs to one of these two spheres. Transfer from one to the other occurs through faith in Christ.

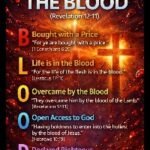

The judicial nature of salvation also appears in Paul’s treatment of forgiveness. In the Epistle to the Colossians 2:13, he writes that God has forgiven believers “all trespasses.” The scope is comprehensive. Forgiveness is not depicted as incremental or conditional upon future penance. Instead, it is grounded in the cancellation of a debt, accomplished through the cross.

Similarly, in the Epistle to the Ephesians 1:7, redemption and forgiveness are said to exist “through his blood.” The emphasis rests on Christ’s sacrificial death rather than on human effort. Paul’s consistent argument is that the believer’s standing depends entirely on that event. The result is either full pardon or continued liability. No third category appears.

The concept of reconciliation reinforces the same polarity. In Romans 5:10, those who believe are described as reconciled to God through the death of His Son. Prior to reconciliation, humanity is characterized as alienated and even hostile. The shift is relational but rooted in legal satisfaction. Peace with God is not an aspiration but a reality for the justified. Conversely, absence of reconciliation implies continued enmity.

Paul’s language about cleansing also operates in definitive terms. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 6:11, addressing believers with troubled pasts, he writes, “such were some of you: but ye are washed, but ye are sanctified, but ye are justified.” The verbs indicate completed actions. Their prior identity no longer defines their current status. The change is not partial reform but a transformation of position.

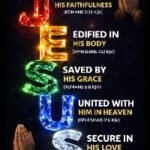

Sanctification in Pauline theology often refers not to gradual moral improvement but to being set apart in Christ. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 1:30, Christ is said to be made unto believers wisdom, righteousness, sanctification, and redemption. The believer’s holiness derives from union with Christ rather than from personal attainment. Thus the line between saved and unsaved is drawn not by comparative morality but by participation in Christ’s holiness.

The legal dimension resurfaces in Romans 3:28, where Paul concludes that a person is justified by faith apart from the deeds of the law. The court metaphor dominates his argument. Charges are either upheld or dismissed. When he asks in Romans 8:33–34, “Who shall lay any thing to the charge of God’s elect?” the implied answer is none. Christ’s atoning work forecloses further prosecution.

Opponents of such categorical language sometimes argue that moral ambiguity persists even among believers. Paul does not deny ongoing struggle with sin. However, he distinguishes between condition and position. The believer’s experience may fluctuate, but his standing before God does not. The certainty arises from Christ’s sufficiency rather than human consistency.

This distinction becomes especially evident in Paul’s discussion of righteousness. In Second Epistle to the Corinthians 5:21, he states that God made Christ to be sin for us, that we might be made the righteousness of God in Him. The exchange is comprehensive. Righteousness is imputed, credited to the believer’s account. Self-generated righteousness, by contrast, is dismissed. In Epistle to the Philippians 3:9, Paul rejects a righteousness of his own derived from the law in favor of that which comes through faith in Christ.

The implication is unavoidable: acceptance with God depends on the righteousness of Christ received by faith. Without that imputed righteousness, a person remains exposed to judgment. Religion may attempt to bridge the gap through rituals or ethical codes, but Paul’s argument is that such efforts cannot satisfy divine justice.

Holiness, too, is treated as positional. In Epistle to the Ephesians 1:4, believers are described as chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world, that they should be holy and without blame before Him. The holiness flows from being in Christ. In Ephesians 2:6, they are said to be seated together in heavenly places in Him. The language suggests a new identity anchored in Christ’s exaltation.

Before that transformation, however, Paul describes humanity in sobering terms. In Romans 5:10 he refers to believers’ former state as enemies. The contrast between hostility and reconciliation underscores the absence of neutrality. A person is either reconciled or remains estranged. The middle ground is not acknowledged.

The theme of adoption adds another dimension to the binary structure. In Epistle to the Galatians 4:4–7, Paul explains that those who receive Christ are adopted as sons and receive the Spirit of adoption. The familial imagery conveys intimacy and belonging. Those outside this relationship are not described as partial members but as strangers to the covenant of promise.

Identity, in Pauline theology, is thus decisively altered at conversion. In Second Epistle to the Corinthians 5:17, he writes that if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creature; old things are passed away, and all things are become new. The language indicates a break rather than a blend. The believer does not straddle two spiritual realities. He transitions from one to another.

This clarity extends to eschatological considerations. In Romans 8:30, those whom God justified are also glorified, presented in a sequence that underscores certainty. The trajectory from justification to glorification is treated as assured. For those outside Christ, however, Paul warns of future judgment. The outcome depends on relationship to Christ in the present.

Critics sometimes contend that such exclusivity fosters division. Paul’s letters, however, locate the division not in human preference but in response to the gospel. The message he summarizes in First Epistle to the Corinthians 15:1–4 — Christ’s death for sins, burial, and resurrection — functions as the decisive announcement. Acceptance or rejection of that proclamation determines spiritual standing.

The urgency of decision appears in Second Epistle to the Corinthians 6:2, where Paul declares, “now is the accepted time; behold, now is the day of salvation.” The present tense suggests immediacy. Delay does not create a neutral category; it perpetuates existing separation.

The apostle’s insistence on grace alone also explains his rejection of works as co-contributors to salvation. When religious observance is introduced as a necessary supplement, the clarity of the divide is obscured. In Galatians, he warns that adding law to grace undermines the gospel itself. For Paul, the integrity of salvation depends on its exclusive grounding in Christ.

This framework carries pastoral implications. Assurance becomes possible because salvation does not rest on fluctuating performance. If justification is a completed legal declaration, then the believer’s security is anchored in Christ’s finished work. Conversely, complacency is challenged by the recognition that without faith in Christ, a person remains under condemnation.

Modern sensibilities often resist binary categories, preferring inclusive language that minimizes separation. Yet the Pauline corpus consistently presents two outcomes. In Adam, condemnation and death. In Christ, justification and life. The starkness is theological rather than rhetorical.

For Paul, the dividing line is not ethnicity, social status, or moral history. It is faith. In Romans 10:9–10, he states that confession of Jesus as Lord and belief in His resurrection result in salvation. The simplicity of the condition intensifies the clarity of the outcome.

The implications extend beyond individual spirituality to communal identity. The church, in Paul’s letters, consists of those who share this faith. Membership is not conferred by heritage or ritual alone. It arises from union with Christ. Thus the community itself reflects the binary nature of salvation: those inside are defined by grace; those outside remain in need of it.

Paul’s theology does not deny complexity in human experience. He acknowledges struggle, doubt, and growth. Yet beneath those variables lies a settled verdict. Either the believer stands justified in Christ, or the unbeliever remains accountable for sin. The gospel does not describe a continuum of partial acceptance.

The clarity may appear severe, but within Paul’s framework it is also liberating. If salvation depended on gradual attainment, certainty would be elusive. By presenting justification as decisive and complete, he offers assurance to those who believe. The same clarity, however, compels urgency toward those who do not.

In examining Paul’s letters as historical documents, one finds consistent use of legal and relational language to describe salvation. Courts render verdicts. Families adopt children. Enemies are reconciled. Debts are canceled. Each image reinforces a definitive change of status. None suggest partial transition.

The modern debate over inclusivity and pluralism often intersects with these themes. Pauline doctrine does not accommodate the notion that sincerity alone suffices. Faith in Christ’s redemptive work remains central. The dividing line is theological rather than sociological.

In summary, the Pauline witness presents humanity in two spiritual conditions. Salvation is portrayed as a decisive act of divine grace received by faith, resulting in justification, reconciliation, and adoption. Those outside that faith remain under condemnation. The categories are not gradational but absolute. Within this doctrinal framework, one is either saved or lost, united with Christ or separated from Him. The clarity may challenge contemporary preferences for ambiguity, yet it remains a defining feature of the apostle’s message.