Unearthing the Scriptures: Biblical Artifacts in the Bible Confirmed by Archaeology

Unearthing the Scriptures: Biblical Artifacts in the Bible Confirmed by Archaeology

MYSTERIES & ARCHAEOLOGYGOSPEL AND SPIRITUALITY

MrTruth.Tv

9/18/202512 min read

For centuries the Bible has been read as scripture, law, history and poetry. For many readers, a separate question has also loomed: how much of the story described between its covers can be tested against the material record—inscriptions, pottery, city ruins and scrolls unearthed by archaeologists? Over the last 150 years, excavations across the Levant have produced a remarkable catalogue of artifacts that illuminate, corroborate, complicate and sometimes challenge the narratives preserved in biblical texts. Some finds are decisive: a carved stone that names a Roman prefect mentioned in the Gospels; an iron-age inscription that appears to refer to the “House of David.” Others are complex or disputed—objects that sparked headlines and courtroom drama before scholars settled into cautious, evidence-driven arguments.

This long-form report surveys the major archaeological discoveries most directly related to persons, places and events in the Bible, explains what they do and do not prove, and places them in the context of modern historical method. It draws on primary excavation reports and reporting from leading institutions: the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Israel Museum, peer-reviewed journals and established archaeology outlets. Where claims have been contested, the article explains the controversy and the current scholarly consensus. imj.org.il+2Biblical Archaeology Society+2

Why material evidence matters — and what it can’t do

Archaeology is not a tool for “proving” theological claims. Instead, it provides an independent record of the past: built environments, inscriptions, everyday objects and texts that can be dated, contextualized and compared with ancient literary sources. A seal impression or an inscribed stone can confirm the existence of a person or polity, or show that a biblical episode fits the social and administrative realities of its time. Conversely, the absence of evidence does not mean absence in reality—archaeology is always partial.

Two common traps are worth avoiding. First: conflating textual confirmation with theological validation. An inscription naming “Pontius Pilate,” for instance, confirms the historical existence of the Roman prefect described in the Gospels; it does not prove or disprove questions of faith. Second: overreaching from a single artifact to broad narratives. Most archaeological finds inform specific details—chronology, names, administrative structures—not the whole sweep of a literary tradition.

Below we trace several of the clearest, most discussed cases where archaeology and the Bible intersect.

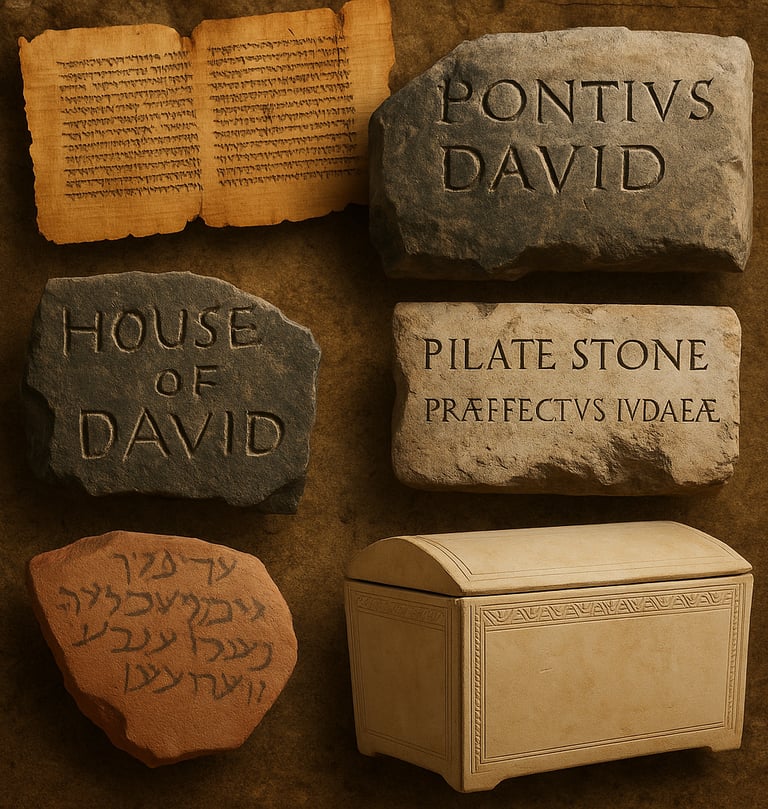

1) The Dead Sea Scrolls — manuscripts that changed the calendar of biblical studies

What was found: Between 1947 and 1956 shepherds and archaeologists discovered fragments and whole scrolls in caves near Qumran on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea. The corpus—now known collectively as the Dead Sea Scrolls—includes biblical manuscripts, sectarian compositions, hymns and legal documents dating roughly from the third century BCE to the first century CE. Some scrolls are near-complete books of the Hebrew Bible; others are fragmentary.

Why it matters: Before the scrolls, the oldest nearly complete Hebrew Bible manuscripts dated to the medieval period (for example, the Leningrad Codex, 10th–11th century CE). The Dead Sea Scrolls pushed the textual witness backward by a millennium and provided direct evidence for the state of biblical texts in the Second Temple period. That allowed textual critics to see which readings were stable, where variations existed, and how the Hebrew Bible reached its later standardized forms. In particular, the scrolls show that multiple textual traditions circulated side-by-side in the ancient world—clear proof that the biblical text was not a single immutable document from antiquity but the product of centuries of editing and transmission. imj.org.il

Key confirmation and limits: The Dead Sea Scrolls confirm that many of the books of the Hebrew Bible were already in circulation by the late Second Temple era and that the scriptural tradition was plural and fluid—an essential datum for both historians and theologians. They do not, however, settle theological questions such as the divine inspiration claimed by religious communities; rather, they provide a secure, datable textual baseline against which later medieval and modern versions are compared.

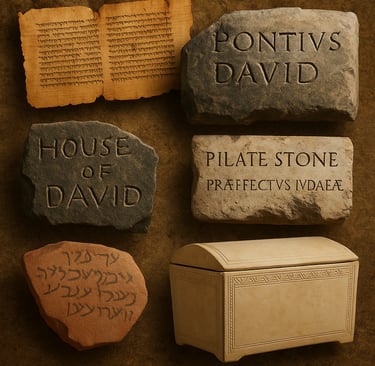

2) The Tel Dan Stele — an inscription that mentions the “House of David”

What was found: In 1993 excavation at Tel Dan in northern Israel uncovered fragments of a basalt victory stele erected by an Aramean king (often identified as Hazael or his successors). The inscription—written in Aramaic and dated to the 9th century BCE—contains a line that has been read as referencing the “House of David” (Hebrew: Beit David). That reading, first publicized in the 1990s, generated immediate scholarly excitement because it provided what many scholars called the first extrabiblical reference to David as a historical figure or to his dynasty. Biblical Archaeology Society

Why it matters: For the long-running debate known as the “biblical minimalists vs. maximalists” dispute, the Tel Dan fragment was a turning point. Minimalists argued that large parts of the biblical narrative—especially the united monarchy of David and Solomon—were literary creations developed much later. The Tel Dan inscription demonstrates that by the 9th century BCE, neighboring polities were aware of a ruling dynasty in Judah identified as the “House of David.” It therefore provides independent, contemporaneous evidence that a dynastic founder named David was remembered in regional political memory. Biblical Archaeology Society

Caveats: The inscription is fragmentary; individual letters and words are debated. But most epigraphers agree that it contains a phrase that can reasonably be read as byt dwd, “House of David.” That makes Tel Dan a keystone in the argument for a historically rooted Davidic dynasty—if not a complete portrait of the united monarchy described in the Bible. Biblical Archaeology Society

3) The Pilate stone — a Roman inscription that names Pontius Pilate

What was found: In 1961 an inscribed limestone block was discovered at Caesarea Maritima during excavations of Herodian-era public buildings. The damaged Latin text contained, in the most widely accepted reconstruction, the name “Pontius Pilate” and the title “prefect of Judea.” The block is often called the Pilate Stone and is now in the Israel Museum. Wikipedia+1

Why it matters: Pontius Pilate is a central figure in the New Testament narrative of Jesus’ trial and execution. Until the discovery of this stone, the only attestations of Pilate came from literary sources—Roman writings and the Christian Gospels. The Pilate Stone provides the first archaeological (hard, physical) confirmation that a Roman official of that name and title administered Judea in the early first century CE—an independent check on New Testament historiography and a vivid example of how epigraphy and archaeology intersect with scripture. Wikipedia

Notes on interpretation: The inscription is not a biblical “proof” of gospel accounts; rather it confirms the historical plausibility of at least one named Roman governor present in the region at the approximate time described by the Gospels. The Pilate Stone is a classic example of archaeology corroborating specific administrative details found in ancient literature. Wikipedia

4) Hezekiah’s Tunnel and the Siloam Inscription — engineering recorded in stone

What was found: Beneath the City of David (the oldest core of Jerusalem) runs an 8th-century BCE tunnel that channels water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam. In 1880 laborers discovered a Paleo-Hebrew inscription carved into the tunnel wall—the Siloam Inscription—describing how two teams of diggers began at opposite ends and met in the middle. The tunnel and inscription are traditionally associated with King Hezekiah’s preparations for an impending Assyrian siege, an episode narrated in 2 Kings 20 and 2 Chronicles 32. Wikipedia+1

Why it matters: The Siloam Inscription is a contemporaneous engineering account that precisely matches the technical feat described in biblical narrative: a defensive water diversion and the excavation of a tunnel under a city to secure water during siege. Such inscriptions are rare in the archaeology of ancient Israel; the Siloam text is often cited as a concrete instance where a biblical description and a physical artifact converge. Wikipedia+1

Recent related finds: Excavations around the Pool of Siloam and related installations have continued to refine our understanding of Second Temple and earlier installations; major work in the 2000s recovered the remains of a stepped pool in situ, linked to the Gospel narrative of Jesus healing the blind man at the pool but also to older urban phases. These discoveries illustrate how urban infrastructure—waterworks in particular—serves as a bridge between text and terrain. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

5) The Merneptah Stele — the earliest extra-biblical mention of Israel

What was found: In 1896 the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie recovered a victory stele (today in Cairo) erected by Pharaoh Merneptah (ca. 1213–1203 BCE). One line in the inscription boasts of victories in Canaan and contains—most notably—the phrase “Israel” as a people or polity in Canaan, making it, for many scholars, the earliest known extrabiblical reference to Israel. Wikipedia

Why it matters: The Merneptah Stele establishes that a social-political entity called “Israel” was known in the highland Canaanite landscape by the late 13th century BCE. It does not confirm the biblical narratives of conquest under Joshua, but it does anchor the name and existence of an Israelite people in the late Bronze–early Iron Age, providing a fixed point for historians reconstructing the deep origins of ancient Israel. Wikipedia

6) The Mesha (Moabite) Stele — a Moabite voice that echoes 2 Kings

What was found: Discovered in the late nineteenth century at Dibon (modern Dhiban, Jordan), the Mesha Stele is a basalt monument erected by King Mesha of Moab (ninth century BCE) commemorating victories over Israel and building works. The inscription contains a reference to the “House of Omri” and recounts events that have clear parallels with the biblical account in 2 Kings 3. Wikipedia+1

Why it matters: The Mesha Stele is a rare non-Israelite inscription that recounts events also narrated in the Hebrew Bible but from the perspective of a neighboring king. It is a vivid example of how comparative epigraphy can illuminate political relations described in biblical texts. The stele corroborates certain geographic and political claims of the biblical narrative, while also reminding readers that ancient histories are contested and propagandistic. Wikipedia+1

7) The Lachish Letters — ostraca that map a kingdom under siege

What was found: In the 1930s excavations at Lachish (Tell ed-Duweir) recovered a group of inscribed pottery sherds—letters—written in late biblical Hebrew and dated to the final years before the Babylonian destruction of Judah (late 7th/early 6th century BCE). The contents are practical and military—warnings, troop movements and pleas—evoking a kingdom on the brink. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

Why it matters: The Lachish ostraca are among the most revealing artifacts for the internal life of Judah during its crisis years. They corroborate the biblical portrayal of the late Judahite monarchy under siege, provide names and offices consistent with biblical lists, and show literacy and administrative communication at the local level. For historians of the prophetic age—Jeremiah, for example—the letters provide contemporaneous context to the narratives of collapse recounted in the Bible. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

8) Ossuaries, names and controversies: Caiaphas, “James,” and the limits of epigraphy

What was found: Archaeological recovery of burial boxes (ossuaries) and inscribed bone-chambers in and around Jerusalem has produced artifacts bearing names of figures that appear in New Testament and extra-biblical sources: one ossuary inscribed “Caiaphas” was linked to the high priest named in the Gospels; another, the so-called “James Ossuary” once generated headlines for an inscription reading “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” Wikipedia+1

Why it matters—and why caution is necessary: Names like “Caiaphas” and “James” were not unique in antiquity; onomastic frequency matters. The Caiaphas ossuary discovered in a burial cave in 1990 is widely accepted as belonging to the high priest Caiaphas, and it remains an important archaeological anchor connecting New Testament nomenclature to a physical context. The James Ossuary, by contrast, became the subject of forgery allegations and a high-profile trial; the legal acquittal of a collector did not fully resolve scholarly doubts about the inscription’s antiquity and authenticity. That episode underscores a crucial reality: the provenance of artifacts, the integrity of the archaeological context, and the possibility of forgeries are central to responsible interpretation. Wikipedia+1

9) What archaeology confirms—and what it complicates

Across the examples above, a pattern emerges. Archaeology repeatedly confirms certain classes of details described in biblical texts:

Names and administrative titles (Pilate Stone, inscriptions referencing Israel, the “House of David”): epigraphy often verifies that people and institutions attested in the Bible were indeed present in the region’s political vocabulary. Wikipedia+2Biblical Archaeology Society+2

Infrastructure and engineering (Hezekiah’s Tunnel, Siloam Pool): material works recorded in inscriptions or physical remains match narrative descriptions of city defenses and waterworks. Wikipedia+1

Local political interplay (Mesha Stele, Tel Dan): inscriptions from neighboring polities corroborate conflicts and alliances reflected in biblical books of Kings and Chronicles. Wikipedia+1

Textual transmission (Dead Sea Scrolls): the scrolls provide a secure textual baseline to understand how the biblical texts evolved and were copied. imj.org.il

But archaeology also complicates claims made by some modern readers who seek a one-to-one confirmation of every episode. The record is fragmentary; some events and personalities leave no direct material trace; later editing, theological shaping and legendary development mean the biblical corpus mixes history with meaning. For instance, archaeological visibility is a function of urban occupation, destruction layers, later reuse of material, and the chance survival of organic materials—conditions that do not preserve every historically real event.

10) Recent discoveries and ongoing work: the record is still growing

Biblical archaeology is not a closed book. New digs, improved dating methods (including radiocarbon calibration and paleographic analysis), and digital tools for reading inscriptions continue to refine—and sometimes revise—previous conclusions. Recent finds at Jerusalem’s City of David and continued study of the Qumran assemblage show the field is active. For example, excavations and geoarchaeological analyses around the Pool of Siloam and the Gihon Spring continue to illuminate water management systems of the First and Second Temple eras. Likewise, the use of imaging technologies and AI in scroll reconstruction has accelerated the pace at which small fragments can be matched and dated. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

Expert voices: how archaeologists read artifacts against texts

Archaeologists and epigraphers approach artifacts with methodological caution. A leading epigrapher will not accept a claim that an inscription proves a textual episode without establishing: (1) secure archaeological context for the object; (2) reliable palaeographic or scientific dating; and (3) careful linguistic analysis to ensure reading and translation are defensible. Institutions such as the Israel Antiquities Authority and museum curators routinely publish excavation reports that subject finds to peer review.

In public debates, scholars often emphasize nuance. For example, the Tel Dan inscription’s invocation of the “House of David” is thrown into public relief as a headline-grabbing confirmation of David, but specialists note the text’s fragmentary state and the need to situate it within broader regional epigraphy. Similarly, the Dead Sea Scrolls do not render later manuscript traditions meaningless; instead they demonstrate the kinds of textual variation that shaped the biblical canon over time. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

Contested artifacts and the politics of provenance

Archaeology’s power to influence public imagination makes it vulnerable—to forgeries, to political pressures over museum holdings, and to sensationalist reporting. The James Ossuary case—an artifact that initially promised direct material linkage to a New Testament family—became entangled in questions of modern inscriptions, the illicit antiquities trade, and courtroom forensics. The moral for students of biblical archaeology is clear: provenance and context matter as much as the artifact itself. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

The Mesha Stele and other artifacts also illustrate an ethical and diplomatic layer. The Mesha Stele sits in the Louvre; Jordan has periodically requested its repatriation. Such debates show that ancient artifacts remain contested political objects—not only windows into the past but symbols of modern national narratives. Wikipedia

What the average reader should take away

Archaeology confirms many specific historical details found in the Bible—names, places, administrative titles and infrastructure—without vouching for theological claims. The Pilate Stone, the Merneptah Stele, the Siloam Inscription and the Tel Dan Stele are widely cited examples where archaeology and biblical texts converge. Biblical Archaeology Society+3Wikipedia+3Wikipedia+3

The textual record is complex. The Dead Sea Scrolls show that the biblical text circulated in multiple forms before later standardization—valuable information for historians, textual critics and religious communities alike. imj.org.il

Context and provenance matter. Isolated finds without archaeological context—or objects with suspicious acquisition histories—must be treated with skepticism. The James Ossuary saga is a cautionary tale of how artifacts can be misrepresented or forged. Bible Interp+1

Archaeology is ongoing. New technologies, excavations, and peer-reviewed analysis mean our understanding continues to evolve; decisive new finds may refine current interpretations or open fresh debates. Recent fieldwork around Jerusalem and continued study of inscriptions and scroll fragments keep the discipline lively. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

Selected further reading and sources

(The list below links to respected institutions, primary excavation reports, and synthesis pieces for readers who want to dive deeper.)

On the Dead Sea Scrolls and their significance: Israel Museum (Shrine of the Book) and review articles summarizing Qumran finds and dating debates. imj.org.il+1

On the Tel Dan Stele and the “House of David” reading: coverage and scholarly discussion in Biblical Archaeology Review. Biblical Archaeology Society

On the Pilate Stone: excavation notes and museum records describing the Caesarea find and inscription. Wikipedia+1

On Hezekiah’s Tunnel and the Siloam Inscription: City of David resources and specialist epigraphic discussions. עיר דוד+1

On the Merneptah Stele (the “Israel Stele”): primary publication and museum records. Wikipedia

On the Mesha Stele (Moabite Stone): translation and commentary, including comparative readings with 2 Kings. Wikipedia+1

On the Lachish Letters: British Museum holdings and scholarly summaries of the ostraca. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

On controversies and forgeries (e.g., James Ossuary) and the legal and scientific debates surrounding authentication: long-form treatments in Biblical Archaeology Review and academic critiques. Biblical Archaeology Society+1

Conclusion: archaeology as conversation, not verdict

Archaeology does not issue verdicts of belief. It provides a material conversation partner for ancient texts: trowel marks, carved letters, fragments of leather and clay that speak across millennia. In many important cases—epigraphic references, administrative artifacts and preserved manuscripts—archaeological evidence confirms that the world described in the Bible had concrete historical contours recognizable to modern scholars. In other cases the material record complicates simple readings and forces historians to pay attention to nuance: political propaganda, textual pluralism, and the vagaries of survival.

The most robust lesson of modern biblical archaeology is humility: the past is more complex than any single book, and the intersection of text and artifact is rarely tidy. But it is also one of the most rewarding intersections in scholarship: where stones and scrolls, inscriptions and stratigraphy, together map a human past that is at once familiar and strange—one that continues to reveal itself to careful, patient, and skeptical inquiry. Wikipedia+3imj.org.il+3Biblical Archaeology Society+3

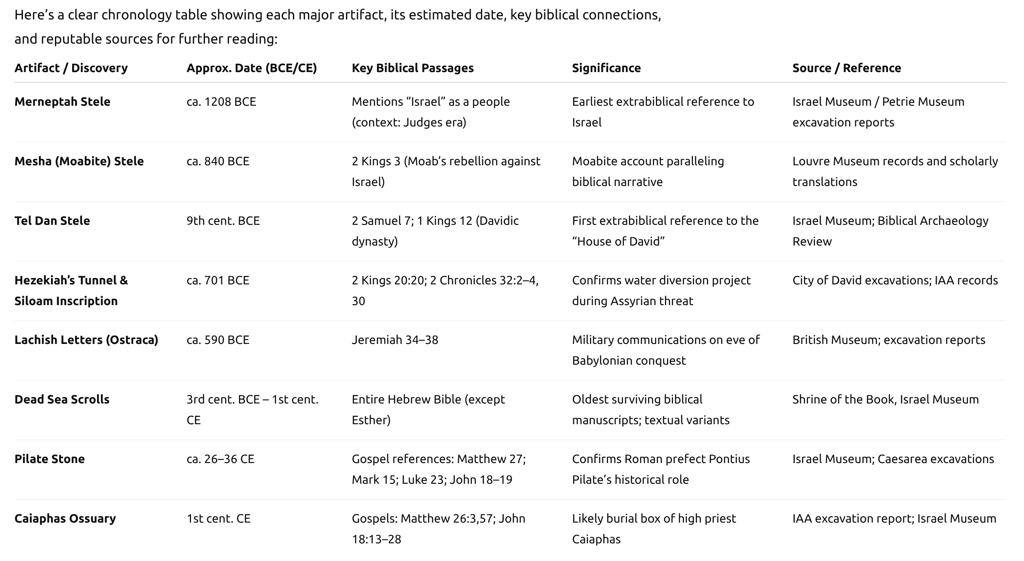

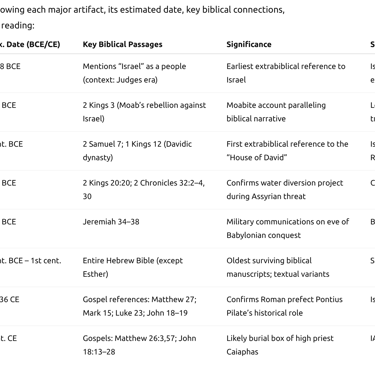

How to Use This Table

Approx. Date is based on current scholarly consensus using paleography, radiocarbon analysis, or historical context.

Key Biblical Passages show where the person, place, or event is mentioned, not necessarily claiming direct one-to-one “proof.”

Source / Reference entries link to excavation reports, peer-reviewed studies, or museum holdings so you can verify details and see high-resolution images.