“Notwithstanding in this rejoice not… but rather rejoice, because your names are written in heaven.”

— Luke 10:20 (KJV)

Across cultures and generations, success has typically been quantified by accumulation and recognition. Economic mobility, professional status, public influence, educational attainment, and relational milestones form the architecture of modern aspiration. From commencement stages to retirement banquets, achievement is charted in promotions secured, assets acquired, and reputations sustained. Even religious communities sometimes absorb these metrics, subtly equating divine favor with visible prosperity or numerical growth.

Yet within the Christian Scriptures there exists a markedly different framework—one that relocates success from the horizontal plane of social measurement to the vertical axis of divine record. In a brief but arresting statement recorded in Gospel of Luke 10:20, Jesus instructs His followers not to anchor their joy in visible demonstrations of spiritual power, but to rejoice “because your names are written in heaven.” That pronouncement shifts the ground beneath conventional ambition. It directs attention away from what can be displayed publicly and toward what is inscribed invisibly.

While that statement precedes the Apostle Paul’s ministry historically, Pauline doctrine expands and clarifies the theological infrastructure that makes such heavenly enrollment possible. In his epistles—particularly Ephesians, Romans, Colossians, and Philippians—Paul constructs a consistent argument: human standing before God is not achieved but granted; not earned by effort but conferred through grace; not maintained by performance but secured by divine action. Within that framework, the decisive marker of spiritual success is whether one belongs to Christ—whether one’s identity is established “in Him.”

The tension between cultural aspiration and biblical assurance is not new. First-century Mediterranean societies also valued honor, lineage, and public acclaim. Patronage systems reinforced hierarchies; inscriptions on civic buildings immortalized benefactors; family names carried generational significance. Into that environment Paul wrote to communities struggling to disentangle inherited assumptions about status from the radically equalizing message of the gospel.

His correspondence to Timothy includes a pointed reminder: “For we brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out” (1 Timothy 6:7). That assertion undercuts the permanence attributed to material accumulation. It does not condemn property ownership outright; rather, it relativizes it. Possession is temporary by design. The human lifecycle—birth without belongings, death without retention—exposes the provisional nature of ownership. Wealth may furnish comfort or influence, but it cannot extend beyond mortality’s boundary.

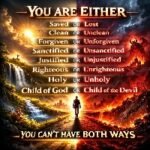

The logic unfolds further in Romans, where Paul outlines humanity’s shared predicament. “All have sinned, and come short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). In that assessment, distinctions of class, ethnicity, and accomplishment collapse. The most decorated résumé and the most obscure existence share a common deficiency before divine holiness. The apostle then introduces the corrective: believers are “justified freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Romans 3:24). Justification, in Pauline vocabulary, is a judicial declaration. It is not self-improvement but a change in legal standing. In effect, the decisive verdict has already been rendered for those who trust in Christ.

When contemporary observers evaluate success, they often rely on comparative metrics—income relative to peers, influence measured by audience size, achievements ranked by prestige. Paul’s letters resist that comparative instinct. In Philippians 3, he recounts his own credentials—heritage, education, religious zeal—and then characterizes them as loss in light of Christ. The passage does not deny the historical reality of those achievements; it reframes their value. What once served as grounds for confidence becomes secondary when measured against the righteousness that comes “through the faith of Christ.”

The idea of a heavenly registry appears again in the broader canon of Scripture, culminating in apocalyptic imagery in Revelation 20:15, where the absence of one’s name from the book of life carries grave consequence. Though Revelation’s genre differs from Paul’s didactic letters, the thematic connection is evident: divine record, not earthly acclaim, determines ultimate outcome. Paul does not dwell on apocalyptic detail, but he repeatedly underscores the permanence of the believer’s new status. In Ephesians 1:13–14, he writes of believers being “sealed with that holy Spirit of promise,” described as the earnest or guarantee of an inheritance. The language is transactional and legal, echoing ancient practices of marking ownership and ensuring fulfillment.

Such language complicates popular religious narratives that equate spiritual success with visible manifestations—numerical growth, dramatic experiences, or public influence. Paul’s measure is quieter yet more profound. It centers on reconciliation. “Being justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (Romans 5:1). Peace, in this context, is not emotional tranquility but the cessation of hostility between humanity and God. That restored relationship forms the bedrock of what could be termed true success within Pauline theology.

This perspective also reorients the meaning of career and vocation. Paul himself engaged in tentmaking, sustaining his ministry through manual labor when necessary. He neither romanticized poverty nor sanctified wealth. Instead, he treated work as a sphere of service rather than self-exaltation. To the Colossians, he wrote, “Whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men” (Colossians 3:23). That directive relocates motivation. Productivity is not primarily a vehicle for prestige but an expression of allegiance. If one’s name is secured in heaven, work becomes response rather than pursuit of validation.

In examining contemporary professional culture, parallels emerge. Corporate ladders, entrepreneurial ventures, and creative industries frequently promise fulfillment through recognition. Metrics—quarterly earnings, subscriber counts, publication citations—offer tangible feedback. Yet history is replete with examples of celebrated figures whose reputations faded within decades. Archives preserve names, but cultural memory shifts rapidly. Paul’s assertion that “the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal” (2 Corinthians 4:18) anticipates this volatility. Visibility does not equate to permanence.

Relationships, too, occupy a central place in modern conceptions of success. Marriage, parenthood, and social networks often serve as indicators of personal achievement. Pauline teaching affirms relational bonds while situating them within a larger eschatological horizon. In 1 Corinthians 7, Paul discusses marriage with pastoral realism, acknowledging its value yet reminding readers that “the fashion of this world passeth away” (1 Corinthians 7:31). His counsel does not depreciate intimacy; it contextualizes it. No human relationship can substitute for reconciliation with God.

Theologically, Paul’s argument hinges on substitutionary atonement and imputed righteousness. In 2 Corinthians 5:21, he writes, “For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him.” The exchange described is comprehensive. Christ bears sin; believers receive righteousness. The result is not partial improvement but transformed standing. From a journalistic standpoint, this claim represents one of Christianity’s most audacious assertions: that moral deficit can be addressed not through cumulative effort but through trust in a completed act.

Critics sometimes interpret such teaching as diminishing ethical responsibility. If righteousness is imputed rather than achieved, does conduct matter? Paul anticipates the objection in Romans 6:1: “Shall we continue in sin, that grace may abound? God forbid.” His response grounds ethical transformation in identity. Those united with Christ participate in His death and resurrection; therefore, they are to “walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4). The sequence is crucial. Conduct flows from position, not the reverse. Success, then, is not measured by moral self-engineering but by participation in a new reality inaugurated by grace.

This doctrinal architecture reshapes the understanding of legacy. In secular discourse, legacy often refers to impact—institutions founded, wealth transferred, movements sparked. Pauline thought redirects attention to inheritance rather than influence. Ephesians 1 speaks of believers obtaining an inheritance, not constructing one. The emphasis falls on what is received from God rather than what is left behind for others. That inheritance is described as incorruptible and secure, contrasting with estates subject to legal disputes and economic fluctuation.

The notion of heavenly citizenship further reinforces this recalibration. In Philippians 3:20, Paul writes, “For our conversation [citizenship] is in heaven.” In the Roman colony of Philippi, civic identity carried weight; citizenship conferred rights and privileges. Paul appropriates that language to describe a superior allegiance. Earthly citizenship may dictate social status, but heavenly citizenship determines eternal destiny. If one’s name is recorded above, the fluctuations of earthly standing cannot ultimately destabilize identity.

Modern sociological research consistently highlights the anxiety generated by performance-based cultures. When worth is tethered to output or approval, insecurity becomes endemic. Pauline theology proposes an alternative grounding: acceptance precedes achievement. In Romans 8:1, Paul declares, “There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus.” The phrase “no condemnation” represents a categorical verdict. It leaves no residual charge. In that light, the believer’s joy is anchored not in fluctuating evaluation but in settled judgment.

The imagery of sealing in Ephesians 1 and 4 suggests permanence. Ancient seals authenticated documents and secured containers. To be sealed by the Spirit implies ownership and protection. Paul connects this sealing to “the day of redemption,” projecting assurance into the future. If success is defined by stability of status, then the believer’s security surpasses any tenure or contract available in temporal systems.

It is important to note that Pauline teaching does not advocate withdrawal from society. On the contrary, Paul envisions believers as ambassadors (2 Corinthians 5:20), representing Christ within their communities. The ambassadorial role presupposes engagement. However, representation differs from self-promotion. The ambassador’s authority derives from the sovereign who sends him. Likewise, the Christian’s identity derives from union with Christ, not from independent accomplishment.

In assessing the claim that true success consists in having one’s name written in heaven, a journalist must grapple with evidentiary questions. The heavenly registry is not empirically verifiable in conventional terms. It rests on trust in divine revelation. Pauline letters repeatedly connect this trust to the proclamation of the gospel. In 1 Corinthians 15:1–4, Paul summarizes the core message: Christ died for sins, was buried, and rose again the third day. The historical claims—death, burial, resurrection—anchor the theological promise. Faith, in Paul’s articulation, is not abstract optimism but reliance on these proclaimed events.

The social implications of this doctrine are significant. If eternal standing is determined by grace through faith rather than by socioeconomic markers, then traditional hierarchies lose ultimate authority. In Galatians 3:28, Paul asserts that distinctions such as Jew and Greek, bond and free, male and female do not confer spiritual advantage in Christ. This leveling does not erase cultural differences but neutralizes them as determinants of salvation. Success, therefore, cannot be monopolized by any demographic group.

Critically, Paul also confronts religious self-reliance. In Romans 10:3, he speaks of those who, “being ignorant of God’s righteousness, and going about to establish their own righteousness, have not submitted themselves unto the righteousness of God.” The pursuit of self-generated righteousness parallels secular ambition in structure if not in content. Both rely on human effort as the basis of validation. Paul’s insistence that justification is “without the deeds of the law” (Romans 3:28) dismantles that framework. Submission replaces striving as the decisive act.

The language of reconciliation in 2 Corinthians 5 introduces relational depth to the discussion. Humanity is portrayed as estranged; God initiates restoration. “God was in Christ, reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing their trespasses unto them.” The non-imputation of trespasses echoes the legal imagery of justification. Where guilt would normally be credited, grace intervenes. For Paul, this reconciled status is the foundation of enduring joy.

When Jesus instructs His disciples in Luke 10:20 to rejoice over heavenly enrollment rather than over demonstrable power, He distinguishes between transient authority and enduring relationship. Pauline theology fills in the doctrinal mechanics: through Christ’s atoning work and the believer’s faith, a permanent change in status occurs. The joy recommended is not triumphalism but assurance.

From a pastoral vantage point, this assurance addresses existential insecurity. Many individuals measure their lives against shifting standards—career trajectories, relational milestones, financial benchmarks. Failure to meet expectations often breeds despair. Pauline doctrine offers a counter-narrative: ultimate worth is not contingent upon cumulative achievement but upon divine declaration. That declaration, once issued, is not subject to revision.

This does not trivialize temporal responsibilities. Paul encourages diligence, generosity, and perseverance. In 1 Corinthians 15:58, after expounding the resurrection, he exhorts believers to be “steadfast, unmoveable, always abounding in the work of the Lord,” adding that such labor “is not in vain in the Lord.” The phrase “in the Lord” is decisive. Work performed within the sphere of union with Christ participates in eternity’s durability. The motivation shifts from self-validation to gratitude.

In contemporary discourse, the phrase “living your best life” often encapsulates aspirational thinking. Pauline thought reframes that aspiration. The best life, in his view, is one reconciled to God and oriented toward eternal inheritance. Suffering, which modern success narratives seek to minimize, occupies a different place in his theology. In Romans 8:18, Paul contends that present sufferings are not worthy to be compared with future glory. The comparison again relies on eschatological perspective.

The durability of a name written in heaven stands in contrast to the fragility of reputation. Public figures frequently experience rapid reversals; accolades can yield to scandal; popularity can evaporate. Paul himself endured both admiration and opposition. Yet his confidence, expressed near the end of his life in 2 Timothy 4:8, rested not in public opinion but in a “crown of righteousness” to be awarded by the Lord. The crown imagery symbolizes recognition from a righteous judge rather than from a fickle audience.

An investigative approach must also consider alternative theological views that place heavier emphasis on perseverance or sacramental participation as determinants of final destiny. Pauline texts have been interpreted in diverse ways across Christian traditions. However, within the stream that foregrounds justification by faith alone, the assurance of heavenly enrollment is immediate upon belief. Ephesians 2:8–9 succinctly states, “For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast.” The exclusion of boasting underscores the non-meritorious character of salvation.

If boasting is excluded, then so too is competitive spirituality. The believer’s confidence rests entirely in Christ’s accomplishment. This recalibrates the emotional center of success from pride to gratitude. Gratitude acknowledges receipt; pride claims authorship. Paul consistently attributes authorship of salvation to God’s initiative.

The final implication concerns time. Earthly success is bound by chronology—career arcs, biological limits, economic cycles. Heavenly inscription, as portrayed in Scripture, transcends time’s erosion. Colossians 3:3 affirms, “For ye are dead, and your life is hid with Christ in God.” The hiddenness suggests security beyond visible fluctuation. When Christ appears, Paul writes, believers will appear with Him in glory (Colossians 3:4). The anticipated unveiling situates present identity within future manifestation.

In sum, the Pauline corpus presents a coherent alternative to prevailing definitions of success. Material abundance, professional stature, and relational fulfillment retain relative value but lose ultimate authority. The decisive criterion becomes reconciliation with God through Christ—a status secured by grace and evidenced by faith. Within that framework, to have one’s name written in heaven is not a poetic flourish but a theological shorthand for justified standing, sealed inheritance, and guaranteed participation in eternal life.

For individuals navigating cultures saturated with performance metrics, this doctrine offers both confrontation and consolation. It confronts the instinct to equate worth with achievement. It consoles by grounding worth in divine action. Whether one commands a corporation or labors in obscurity, whether one’s accomplishments are publicly celebrated or quietly unnoticed, the essential question in Pauline thought is unchanged: Are you in Christ?

If so, success has already been secured at the deepest level. If not, no accumulation can compensate for its absence. Cars deteriorate, properties transfer ownership, careers conclude, relationships shift, reputations fade. But a name recorded in heaven—according to the apostolic witness—remains. In that enduring inscription, Paul locates the believer’s joy, confidence, and hope. True success, by this measure, is not constructed over decades of striving. It is received in a moment of faith and sustained by the promise of God.