“As ye have therefore received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk ye in him.”

— Colossians 2:6 (KJV)

In contemporary discussions about Christianity, few tensions surface more frequently than the relationship between grace and responsibility. If salvation is granted freely and not earned, what obligations remain for the believer? Does the emphasis on grace diminish moral seriousness, or does it create a new framework for living? The Apostle Paul’s letters address these questions directly, presenting a vision of Christian duty that is neither legalistic nor permissive, but rooted in identity.

A concise summary of this perspective appears in Epistle to the Colossians 2:6: “As ye have therefore received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk ye in him.” The structure of the statement is instructive. Reception precedes conduct. The believer’s walk flows from having received Christ, not from striving to obtain Him. The sequence reflects a broader Pauline pattern: position first, practice second.

This ordering distinguishes Christian duty from religious obligation. In systems built upon law, behavior secures acceptance. In Paul’s theology, acceptance establishes a new pattern of behavior. The foundation is not human achievement but divine accomplishment. Duty, therefore, is not a means of earning favor; it is an expression of an already granted status.

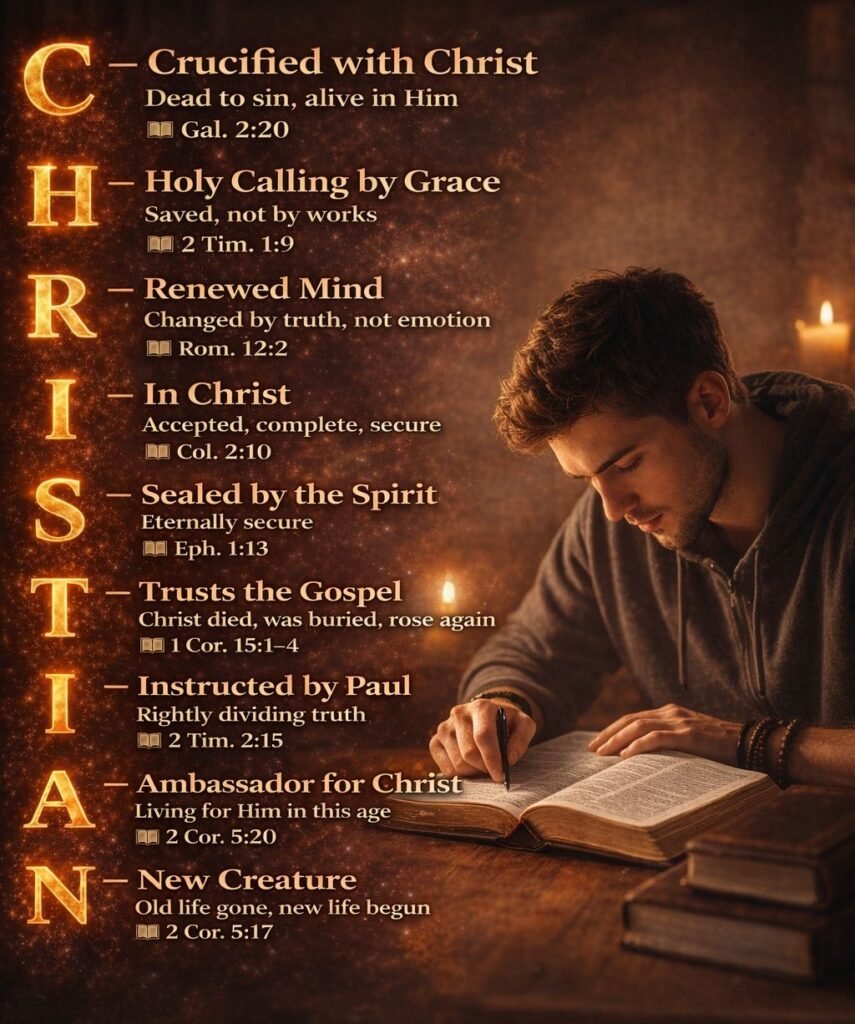

Paul’s explanation of union with Christ forms the core of this outlook. In Epistle to the Galatians 2:20, he writes, “I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me.” The statement is both personal and representative. The believer is identified with Christ’s death. This identification alters the framework of obligation. The old relationship to sin and law has been judged at the cross.

The concept is developed further in Epistle to the Romans 6:6, where Paul explains that the “old man” is crucified with Christ so that the body of sin might be rendered inoperative. Duty, then, arises from a new reality. The believer is not attempting to reform the old self but to live from a new identity established in Christ.

Romans 8:3 adds another dimension by declaring that God condemned sin in the flesh through Christ’s sacrifice. The condemnation that once rested on the sinner was borne by Christ. This transfer has ethical implications. If sin has been judged in Christ, the believer is called to reckon that truth in daily conduct. Responsibility is grounded in redemption.

The apostle’s emphasis on calling further clarifies the nature of Christian duty. In Second Epistle to Timothy 1:9, he describes believers as saved and called with a holy calling, not according to works, but according to divine purpose and grace. The calling is heavenly in orientation, as reflected in Epistle to the Philippians 3:14, where Paul speaks of pressing toward the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus.

This calling is not achieved through effort but received through grace. Nevertheless, it carries implications. Romans 12:1 urges believers to present their bodies as living sacrifices, a reasonable service in light of God’s mercies. The appeal is grounded in prior grace. The response is voluntary dedication, not coerced compliance.

Central to this transformed life is the renewal of the mind. In Epistle to the Romans 12:2, Paul instructs believers not to be conformed to this world but to be transformed by the renewing of their minds. The transformation is intellectual and moral. It involves reorienting thought patterns according to revealed truth.

This renewal stands in contrast to cultural conformity. In Epistle to the Colossians 2:8, Paul warns against being taken captive through philosophy and empty deceit rooted in human tradition. Christian duty includes discernment. The believer evaluates ideas through the lens of apostolic teaching rather than absorbing prevailing assumptions uncritically.

The renewed mind is not an abstract ideal but the basis for practical decision-making. Paul suggests that through transformation believers may prove what is good and acceptable and perfect will of God. Duty, therefore, involves thoughtful engagement with doctrine. It is not reduced to emotional fervor or external compliance.

Identity remains the controlling theme. In Colossians 2:10, believers are described as complete in Christ. This completeness removes insecurity as a motivator. The Christian does not serve to compensate for deficiency but because sufficiency has already been granted. The righteousness required for acceptance has been credited through Christ, as stated in Second Epistle to the Corinthians 5:21.

Security undergirds this identity. In Epistle to the Ephesians 1:13, Paul explains that believers are sealed with the Holy Spirit of promise after believing the gospel. The seal signifies ownership and authenticity. It is not provisional. Ephesians 4:30 indicates that this sealing endures until the day of redemption.

The indwelling Spirit is not merely a guarantee of future inheritance but an active presence shaping present conduct. Romans 8:11 states that the Spirit who raised Christ from the dead dwells in believers. The implication is dynamic: the same power that effected resurrection energizes daily life. Duty, in this light, is empowered obedience rather than self-generated effort.

Paul’s understanding of the gospel itself also informs Christian responsibility. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 15:1–4, he outlines the gospel by which believers are saved: Christ died for sins, was buried, and rose again. This message is not confined to initial conversion. He urges the Corinthians to stand in it. Ongoing stability derives from continual reliance on the gospel’s truth.

The connection between doctrine and duty appears repeatedly in Paul’s instructions to Timothy. In Second Epistle to Timothy 2:15, Timothy is exhorted to study diligently, rightly dividing the word of truth. Accurate handling of revelation shapes appropriate conduct. Misinterpretation leads to imbalance, particularly when law and grace are confused.

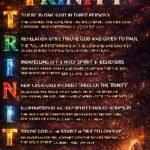

Paul refers to a “mystery” revealed to him concerning the Body of Christ, as described in Epistle to the Ephesians 3:1–5. Understanding this revelation clarifies the believer’s position and responsibilities in the present age. Duty is informed by recognizing one’s place within this redemptive framework.

Another dimension of Christian obligation emerges in Paul’s description of believers as ambassadors. In Second Epistle to the Corinthians 5:20, he writes that believers are ambassadors for Christ, imploring others to be reconciled to God. The role is representational. It carries authority derived from Christ and responsibility to communicate faithfully.

This ambassadorial function is not self-appointed. It flows from reconciliation already received. Those who have been reconciled are entrusted with the ministry of reconciliation. The message centers on grace rather than legal demand. Paul’s appeal is grounded in completed atonement, not in impending political rule or national restoration.

The ethical implications of new creation also shape daily life. In 2 Corinthians 5:17, Paul states that anyone in Christ is a new creature. The old has passed; the new has come. The assertion does not deny the persistence of temptation, but it establishes a new orientation. Conduct consistent with the old identity is incongruent with the new.

Paul’s discussion of the fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5:22–23 further clarifies the character of Christian duty. Love, joy, peace, and other virtues arise from the Spirit’s work rather than from external compulsion. The absence of law against such qualities underscores their alignment with divine intent. The believer’s responsibility includes walking in the Spirit rather than gratifying the flesh.

Freedom from condemnation, articulated in Romans 8:1, does not produce indifference but gratitude. Service motivated by gratitude differs from service driven by fear. The Christian’s obedience reflects appreciation for grace already given.

The social dimensions of Christian duty also appear in Paul’s letters. He addresses relationships between spouses, parents and children, masters and servants. These instructions are grounded in identity in Christ. Mutual submission, love, and fairness flow from shared participation in the same Lord.

Financial integrity, generosity, and contentment receive attention as well. Paul commends the Macedonian believers for giving beyond expectation, not under compulsion but willingly. Duty in material matters arises from recognition of grace rather than from imposed quotas.

Perseverance in suffering forms another aspect of responsibility. Paul frequently recounts his own hardships. Yet he frames endurance as participation in Christ’s sufferings and as testimony to the gospel’s power. The believer’s duty includes steadfastness rooted in hope.

Hope itself functions as motivation. In First Epistle to the Thessalonians 4:16–17, Paul describes the future gathering of believers to meet the Lord. This expectation encourages holy living and mutual comfort. Future assurance shapes present behavior.

The apostle’s own example provides a template. He labors, teaches, and suffers without presenting himself as indispensable. In 1 Corinthians 3, he describes himself and Apollos as servants through whom others believed. God gives the increase. This humility informs the believer’s approach to service.

Accountability remains present in Pauline thought. In Romans 14:10–12, he reminds believers that each will give account of himself to God. This evaluation concerns service and faithfulness rather than salvation. Nevertheless, it reinforces seriousness in conduct.

The cumulative portrait that emerges from Paul’s letters is cohesive. Christian duty is inseparable from Christian identity. Grace does not eliminate responsibility; it relocates it. The believer acts not to secure salvation but because salvation has been secured. The law is not the governing principle; union with Christ is.

This approach avoids two extremes. It rejects legalism, which measures spirituality by compliance with external codes. It also rejects antinomianism, which misconstrues grace as license. Instead, it situates conduct within a relational and doctrinal context.

The emphasis on studying apostolic teaching safeguards against drift. Without doctrinal grounding, enthusiasm may lack direction. With it, obedience becomes informed and purposeful. Paul’s letters consistently bind belief and behavior.

In contemporary contexts where performance metrics dominate many spheres, the Pauline framework offers a different calculus. Faithfulness, integrity, and growth in Christlikeness outweigh visibility or acclaim. The believer’s duties are spiritual realities flowing from participation in Christ’s death and resurrection.

“As ye have therefore received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk ye in him.” The sequence remains decisive. Reception precedes walking. Identity shapes conduct. Grace initiates, and gratitude responds. The spiritual duties of the Christian, as articulated by Paul, are not burdens imposed to gain favor but expressions of a life already transformed by it.