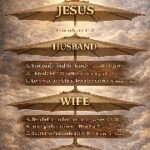

“For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church…” — Ephesians 5:23 (KJV)

Public debate about marriage has intensified in recent decades, often centering on questions of authority, equality, and identity. In many Western societies, the language of hierarchy is treated with suspicion, particularly when applied within the home. Against that backdrop stands a passage from Ephesians 5:23: “For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church.” The verse has been alternately defended as sacred order and criticized as a relic of patriarchy. Its meaning depends largely on how one defines the term “head,” and even more significantly, how one understands the comparison to Christ.

The Apostle Paul’s letters provide the primary theological framework for interpreting this language. Writing in the first century to assemblies scattered across the Roman Empire, Paul addressed communities situated within a strongly patriarchal culture. Roman law vested extensive authority in the paterfamilias, the male head of household, who wielded legal control over property and family members. Yet Paul’s treatment of marital relationships diverges sharply from the prevailing norms of his day. Rather than reinforcing unchecked male dominance, he reframes authority through the lens of Christ’s self-giving love.

To understand the claim, it is necessary to examine Paul’s broader doctrine of Christ’s headship. In Colossians 1:18, Paul writes that Christ “is the head of the body, the church.” The metaphor signals source, authority, and organic connection. Christ’s headship is not arbitrary rule but life-sustaining leadership. The church derives its direction, vitality, and unity from Him. When Paul applies similar terminology to marriage, the analogy is not incidental. The husband’s role is patterned after Christ’s relationship to His redeemed community.

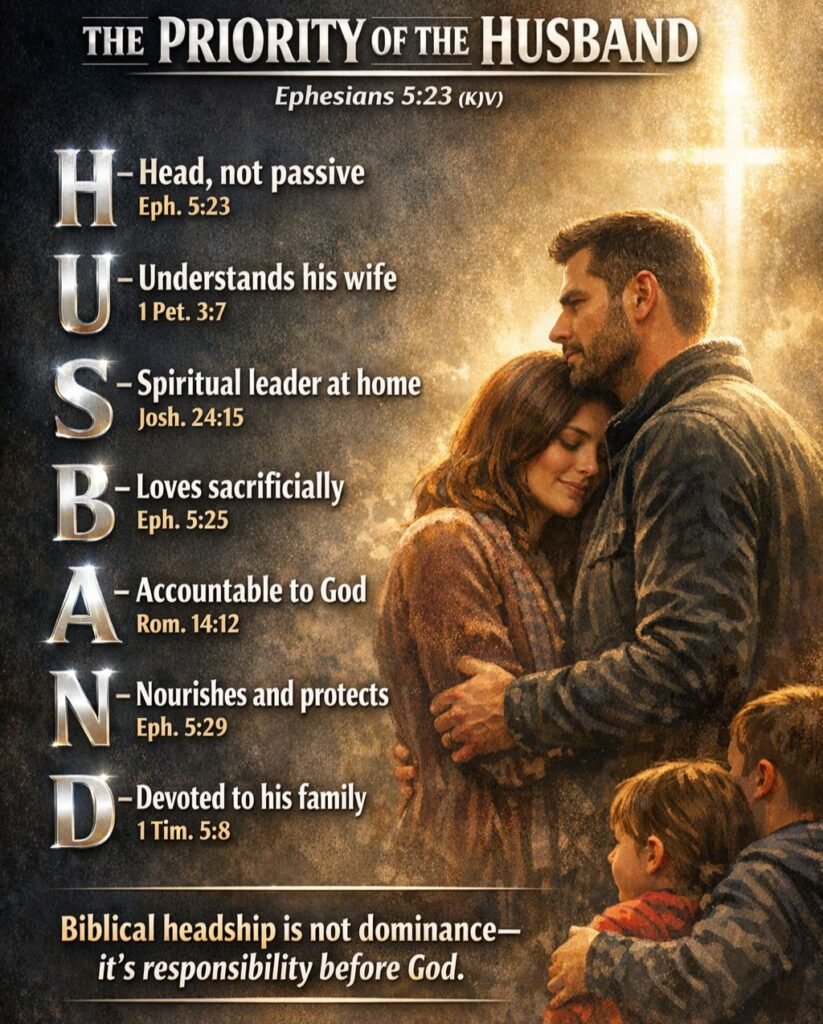

This comparison immediately narrows the scope of acceptable behavior. Christ’s authority is inseparable from sacrifice. In Ephesians 5:25, husbands are instructed to love their wives “even as Christ also loved the church, and gave himself for it.” The standard is not cultural convention but the cruciform model of the gospel. Leadership, in Pauline thought, cannot be detached from self-denial. The same letter that assigns headship to husbands also commands them to love in a manner defined by the cross.

Scholars have long noted that Paul’s instructions to husbands are more extensive than those addressed to wives in Ephesians 5. That imbalance is significant. In a culture where male prerogative was assumed, Paul concentrates his corrective energy on the one who possessed social power. He does not instruct husbands to enforce submission but to embody sacrificial devotion. The weight of responsibility falls squarely on the husband’s shoulders.

The structure of Paul’s argument in Ephesians flows from theology to practice. Earlier in the epistle, he expounds on salvation by grace, the believer’s union with Christ, and the sealing of the Holy Spirit. Marriage instructions appear only after these doctrinal foundations are established. This sequence suggests that marital conduct is an outworking of spiritual identity. Authority in the home is not autonomous; it operates under the lordship of Christ.

In Romans 14:12, Paul reminds believers that “every one of us shall give account of himself to God.” Applied to marriage, the principle implies that a husband’s leadership is subject to divine evaluation. Authority is therefore derivative and accountable. The husband is not the ultimate sovereign in the household; Christ is. The husband answers to a higher tribunal.

This accountability reshapes the meaning of headship. Rather than serving as a license for unilateral decision-making, it imposes a burden of stewardship. The husband must consider how his actions reflect the character of Christ. Paul’s letters repeatedly connect leadership with service. In Philippians 2:5–8, he urges believers to adopt the mind of Christ, who “made himself of no reputation” and “humbled himself.” Though that passage addresses the broader Christian community, its implications for marriage are evident. If Christ’s authority was expressed through humility, then any form of marital leadership divorced from humility contradicts its own theological foundation.

Critics often argue that hierarchical language inevitably produces inequality. Paul’s vision, however, coexists with a robust affirmation of spiritual equality. In Galatians 3:28, he writes that in Christ “there is neither Jew nor Greek… there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one.” The statement does not erase gender distinctions, but it nullifies them as grounds for spiritual superiority. Both husband and wife stand justified by grace, sealed by the Spirit, and heirs of the same promise. The husband’s role does not confer greater value before God.

The question then becomes practical: what does responsible headship entail in daily life? Paul offers several indicators across his letters. In Ephesians 5:29, he notes that no one “ever yet hated his own flesh; but nourisheth and cherisheth it.” The verbs imply ongoing care. To nourish suggests provision; to cherish suggests tender regard. Applied to marriage, the husband’s leadership must prioritize his wife’s well-being, both materially and emotionally. Neglect contradicts the model of Christ, who sustains His body.

In 1 Timothy 5:8, Paul addresses provision more directly: “But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith.” The verse has often been cited in discussions of financial responsibility. Yet its scope extends beyond income. Provision includes stability, protection, and presence. In the ancient world, economic security was closely tied to male labor. Paul’s admonition underscores that spiritual credibility is compromised when domestic obligations are ignored.

Protection also emerges as an implied duty. While Paul does not frame it in militaristic terms, his broader theology of spiritual warfare in Ephesians 6 suggests that believers must stand against destructive forces. Within marriage, this vigilance translates into guarding the household against influences that undermine faith or unity. The husband’s leadership should foster an environment where spiritual growth is encouraged rather than hindered.

Communication forms another essential component. Although Paul does not devote extended passages to marital dialogue, his exhortations regarding speech in Ephesians 4—“Let no corrupt communication proceed out of your mouth, but that which is good to the use of edifying”—apply directly within the home. Authority expressed through harsh or belittling words fails to mirror Christ’s gentleness. Edification, not intimidation, aligns with Pauline ethics.

It is also noteworthy that Paul frames marital instruction within mutual submission. Ephesians 5:21 precedes the specific commands to wives and husbands: “Submitting yourselves one to another in the fear of God.” Interpretations vary regarding how this verse interacts with the subsequent directives, but its presence establishes a climate of reciprocity. While roles may differ, reverence for Christ governs both partners. The husband’s headship operates within a broader call to humility shared by all believers.

Historical context further illuminates the radical nature of Paul’s teaching. In Greco-Roman household codes, wives, children, and slaves were typically addressed as subordinates, with little emphasis on the moral obligations of male heads. Paul, however, places explicit ethical demands on husbands. He does not merely instruct wives to adapt; he commands husbands to transform. The expectation that a husband love sacrificially would have stood in contrast to prevailing assumptions of male entitlement.

Theologically, Paul’s understanding of marriage is inseparable from the mystery of Christ and the church. In Ephesians 5:32, he describes the union as a “great mystery,” referring to the relationship between Christ and His redeemed people. Marriage thus functions as a living testimony. The husband’s conduct communicates something about Christ’s character. This representational dimension intensifies the seriousness of the role. Misuse of authority distorts the image Paul intends marriage to portray.

Modern applications of headship must wrestle with changing social realities. Economic patterns have shifted; dual-income households are common; cultural expectations regarding gender roles continue to evolve. Pauline doctrine does not prescribe specific vocational arrangements. It does, however, insist on certain relational principles: sacrificial love, accountability to God, provision, and spiritual leadership. These principles transcend economic models.

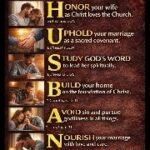

Spiritual leadership in the home does not require theatrical displays of religiosity. Paul emphasizes consistency rather than spectacle. In Colossians 3:16, he encourages believers to let the word of Christ dwell in them richly. For a husband, this implies familiarity with Scripture and a willingness to shape household priorities accordingly. Decisions about time, resources, and values should reflect biblical conviction. Passive disengagement from spiritual matters contradicts the role Paul describes.

At the same time, authoritarian control masquerading as spirituality finds no support in Pauline texts. In 2 Corinthians 1:24, Paul clarifies his own apostolic stance: “Not for that we have dominion over your faith, but are helpers of your joy.” If an apostle refrains from coercive dominion, a husband cannot claim greater latitude. Leadership aimed at fostering joy and faith mirrors the apostolic example more faithfully than rigid command.

The relationship between authority and love is central. In contemporary discourse, authority is often equated with power over others. Paul redefines power through the lens of the cross. In 2 Corinthians 12:9, he recounts Christ’s words: “My strength is made perfect in weakness.” Strength, paradoxically, is displayed through dependence on divine grace. For husbands, this means acknowledging limitations and seeking God’s help rather than asserting infallibility.

The dynamic also involves listening. Although Paul does not articulate listening as a discrete command to husbands, his broader exhortations to patience, kindness, and long-suffering (as in Colossians 3:12–14) presuppose attentiveness. A husband who disregards his wife’s perspective undermines unity. Responsible headship requires informed decisions, and information is obtained through attentive engagement.

In evaluating the practical outworking of these principles, it is instructive to consider the concept of covenant. Marriage, in biblical thought, is not a provisional arrangement contingent upon convenience. It is a binding commitment. Paul’s insistence that husbands love their wives “as their own bodies” underscores permanence. Self-harm is irrational; so is indifference toward one’s spouse. The analogy reinforces interconnectedness.

The potential for abuse remains a serious concern in discussions of headship. History offers sobering examples of religious language weaponized to justify control or violence. Pauline doctrine, properly understood, condemns such distortions. Christ’s headship is never exploitative. He gives Himself for the church’s sanctification and glory. Any behavior that degrades or endangers a wife stands in contradiction to the very model cited in Ephesians 5.

Accountability to God provides an additional safeguard. Romans 14:10–12 portrays believers standing before Christ’s judgment seat. For husbands, this prospect should instill sobriety. Decisions made in private carry eternal significance. The awareness of divine scrutiny discourages complacency and self-justification.

Furthermore, Paul’s teaching on love in 1 Corinthians 13 offers a detailed portrait applicable within marriage. Love is patient and kind; it does not envy, boast, or behave unseemly. Though the chapter addresses spiritual gifts within the church, its description of love’s character transcends context. A husband’s authority devoid of these qualities fails the apostolic test.

The interplay between cultural expectations and biblical conviction can create tension. In societies that prize individual autonomy, submission and headship may appear antiquated. Yet Paul’s framework does not revolve around suppressing individuality. Instead, it calls both husband and wife to align personal desires with allegiance to Christ. The husband’s leadership is one expression of that alignment, not an assertion of personal supremacy.

The domestic sphere often reveals character more transparently than public life. Professional competence does not automatically translate into marital faithfulness. Paul’s criteria for church leadership in 1 Timothy 3 include managing one’s own house well. The logic is straightforward: spiritual credibility is tested at home. A husband who neglects his family while pursuing public acclaim undermines his witness.

In examining Pauline headship, one must also consider the transformative impact of grace. Earlier in Ephesians, Paul describes believers as once alienated but now reconciled. This transformation extends into relationships. Headship under grace is not static; it matures as the husband grows in Christlikeness. Failures are addressed through repentance and renewed dependence on divine strength.

The cumulative portrait that emerges from Paul’s writings is demanding. It requires humility, sacrificial love, accountability, provision, spiritual attentiveness, and perseverance. It does not promise ease. Indeed, the call to love as Christ loved implies enduring hardship for another’s good. Yet Paul consistently roots these obligations in the prior reality of redemption. The husband leads not to secure favor with God but because he already stands within grace.

In contemporary application, couples who embrace this vision often describe a dynamic distinct from both authoritarianism and egalitarian negotiation. The husband bears a conscious sense of responsibility for the spiritual climate of the home. He initiates prayer, models repentance, seeks counsel when needed, and prioritizes unity. The wife, assured of sacrificial love, responds with respect and partnership. While imperfections persist, the governing principle remains Christ-centered fidelity.

Public discourse may continue to debate the viability of headship in modern contexts. Pauline doctrine, however, measures success not by cultural approval but by conformity to Christ. The husband’s role, as articulated in Ephesians 5:23, is inseparable from the cross-shaped love defined in the same chapter. Authority divorced from sacrifice ceases to be biblical headship.

Ultimately, the question confronting Christian husbands is not whether they possess authority, but how they exercise it. If Christ is truly the head of the church, then every husband’s leadership exists under His lordship. The home becomes a place where theological convictions assume practical form. Faithfulness in this sphere may never attract public recognition, yet within Pauline thought, it carries enduring significance.

Biblical headship, therefore, is neither cultural nostalgia nor unchecked control. It is a structured responsibility before God, modeled on Christ’s redemptive love and sustained by grace. The husband is called to lead, but always as one who first bows to a higher Head. In that posture of humility and devotion, marriage reflects not dominance, but disciplined care—an order designed not to diminish, but to protect and nurture.