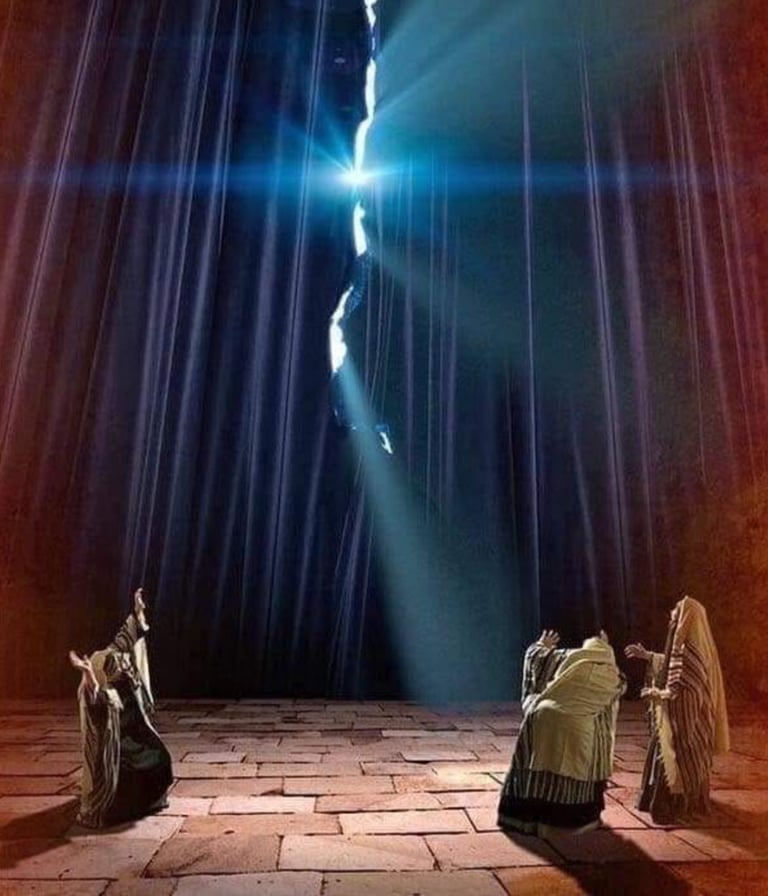

𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗗𝗔𝗬 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗩𝗘𝗜𝗟 𝗪𝗔𝗦 𝗧𝗢𝗥𝗡

𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗗𝗔𝗬 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗩𝗘𝗜𝗟 𝗪𝗔𝗦 𝗧𝗢𝗥𝗡

GOSPEL AND SPIRITUALITY

MrTruth.Tv

12/9/20257 min read

On a spring afternoon nearly two millennia ago, in the city of Jerusalem, something happened that would become one of the most symbolically loaded moments in religious history. The Gospels describe it in stark, cinematic language: “At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split.” (Matthew 27:51)

That detail—the tearing of the veil—might appear minor compared to the crucifixion itself, but scholars, theologians, and historians agree it carried seismic meaning. For Christians, the tearing of the temple curtain represented the end of an era, the shattering of barriers between God and humanity, and the beginning of direct access to the divine through Christ. For historians of Judaism and the Roman world, it underscores the political and religious turbulence of first-century Judea.

This is the story of that day, its background, and why the torn veil continues to resonate across centuries.

The Temple in Jerusalem: A Sacred Center

To understand why the veil mattered, we must first grasp the role of the Temple in Jewish life. The Second Temple, expanded on a grand scale by Herod the Great, was not just a building; it was the spiritual, political, and cultural heart of Jewish identity.

According to Josephus, the Jewish historian writing in the first century, Herod’s reconstruction of the Temple was a project of staggering ambition. “The whole enclosure was about a furlong square,” Josephus notes in The Jewish War, emphasizing its scale. Inside this complex stood the innermost chamber—the Holy of Holies.

The Holy of Holies, separated by a thick veil or curtain, was believed to be the earthly dwelling place of God’s presence. Only the High Priest could enter, and only once a year, on Yom Kippur, to offer atonement for the people’s sins.

The veil itself was no ordinary drape. Ancient sources describe it as massive, possibly 60 feet high and several inches thick, embroidered with symbolic imagery of the heavens. Its purpose was both practical and theological: to mark a line that could not be crossed by ordinary mortals.

Crucifixion Day: Darkness and Earthquake

The crucifixion of Jesus took place during the Jewish festival of Passover, likely around 30–33 CE. All four Gospels mention extraordinary natural phenomena accompanying his death.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke record that darkness fell over the land from noon until three in the afternoon (Mark 15:33–38). Matthew alone adds the detail of the earthquake and the splitting of rocks.

But what unites all three Synoptic Gospels is the detail of the torn temple veil. For example:

“The curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom.” (Mark 15:38)

“The curtain of the temple was torn in two.” (Luke 23:45)

The detail of “from top to bottom” suggests something supernatural—that this was no ordinary tear caused by human hands.

Symbolism: Barriers Broken

For early Christians, the torn veil became an unmistakable metaphor. The curtain had symbolized separation—between God’s holiness and human sinfulness, between heaven and earth, between priest and people. Its tearing suggested a new access point.

The Letter to the Hebrews makes this explicit: “Having therefore, brethren, boldness to enter into the holiest by the blood of Jesus,

By a new and living way, which he hath consecrated for us, through the veil, that is to say, his flesh;” (Hebrews 10:19–20).

In other words, the physical tearing of fabric became a theological claim: Christ’s death had removed the barrier between humanity and God.

Symbolism: From Separation to Access

Scholars from diverse traditions converge on the idea that the torn veil symbolizes direct access to God. The New Testament letter to the Hebrews explicitly connects Jesus’ sacrifice with “a new and living way” into God’s presence (Hebrews 10:19-22).

Key interpretations:

Abolition of Temple Sacrifices: With Jesus as the ultimate atoning sacrifice, animal offerings were no longer required.

Universal Inclusion: The barrier between Jew and Gentile, male and female, priest and layperson collapses (Galatians 3:28).

God Dwelling with Humanity: Christians believe the Holy Spirit now indwells believers, making the community of faith a new temple (1 Corinthians 3:16).

Historical and Scholarly Debates

Historians and theologians debate the literal versus symbolic reading of the event. Was the veil actually torn, or was this narrative detail inserted later to emphasize theological meaning?

Historical Considerations

Did the veil literally tear? Historians weigh the claim:

Natural Explanations: Earthquake damage is plausible; seismic activity around Jerusalem is documented (Geological Society of America).

Symbolic Narrative: Others argue the event serves as theological midrash—an inspired symbol rather than a historical report (Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus).

Importantly, the Gospel writers intended both theological depth and eyewitness credibility, situating the tearing as a public sign witnessed by priests and worshipers.

Archaeological Echoes

Although the temple was destroyed in 70 CE, discoveries like the Western Wall and recently unearthed priestly quarters give texture to our understanding (Israel Antiquities Authority). Pilgrims who pray at the Wall today symbolically approach the Holy of Holies, a tradition infused with the memory of the veil.

Arguments for Symbolic Interpretation

Many scholars suggest the story is not a record of a physical event but a theological metaphor crafted by Gospel writers. The detail is absent from the Gospel of John, written later, which instead emphasizes the words of Jesus: “It is finished.”

The historian Bart Ehrman, for instance, argues that the tearing of the veil may not be historical fact but a symbolic literary device (Bart Ehrman Blog).

Arguments for Literal Interpretation

Others contend that something dramatic did happen in the Temple that day, whether by earthquake damage or divine act. The Jewish Talmud mentions strange occurrences in the Temple around 40 years before its destruction in 70 CE, though not the veil specifically (Sefaria.org).

The Veil and the Destruction of the Temple

The torn veil also foreshadows another cataclysm: the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE.

For Christians, this destruction reinforced the belief that the old system of sacrifices and Temple rituals had ended. As E.P. Sanders, a leading scholar of early Christianity, explains in Judaism: Practice and Belief, the fall of the Temple forced Judaism itself to adapt, shifting toward rabbinic teaching and synagogue worship (Oxford Academic).

Thus, the torn veil became not only a Christian theological image but also a harbinger of seismic historical change.

Resonance Across Traditions

The veil’s tearing reverberates across religious traditions:

In Christianity: It symbolizes salvation, direct access to God, and the priesthood of all believers.

In Judaism: While not a central motif, the imagery underscores the sanctity of the Temple and the tragedy of its destruction.

In broader spirituality: It has come to signify the removal of illusions, the breaking of barriers, and the unveiling of truth.

The metaphor of a “veil” appears in many traditions. Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 3:16 that the veil is lifted when one turns to Christ. In Eastern philosophies, “veil” often describes ignorance or maya that obscures ultimate reality (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Cultural Representations

Artists, writers, and filmmakers have returned again and again to this moment.

Art: From Renaissance paintings to modern Christian iconography, the torn veil appears as a dramatic backdrop to the crucifixion scene.

Film: In movies like The Passion of the Christ (2004), the tearing of the veil is portrayed as a supernatural cataclysm, underscoring the cosmic significance of Christ’s death.

Literature: The image has inspired poetry and sermons, emphasizing themes of freedom, reconciliation, and revelation.

Modern Theological Reflections

Today, theologians reflect on the torn veil in light of issues such as inclusivity, justice, and spirituality.

Inclusivity: The torn veil is often invoked in discussions about access—whether to God, to leadership, or to community. It challenges exclusivity and privilege.

Justice: Some interpreters see the torn veil as God’s declaration that oppressive systems cannot stand forever.

Personal spirituality: For many believers, the image resonates as an invitation to intimacy with the divine without mediation.