The Ancient Blueprint of Humanity: Inside the Bible’s Table of Nations

The Ancient Blueprint of Humanity: Inside the Bible’s Table of Nations

GOSPEL AND SPIRITUALITY

MrTruth.Tv

9/15/20258 min read

The Ancient Blueprint of Humanity: Inside the Bible’s Table of Nations

The Table of Nations — Genesis 10 in most Bibles — reads at first like a dry genealogical register: three branches (Shem, Ham, Japheth), dozens of names, and a few embedded place-names (Canaan, Elam, Javan). But beneath that surface it is one of the Bible’s most ambitious, compact, and theologically charged attempts to map the human family. The list does more than trace ancestry: it defines the known world, claims a shared origin for diverse peoples, negotiates relationships between Israel and its neighbors, and encodes an ancient worldview about order, migration, and divine governance. This article unpacks Genesis 10 as an “ancient blueprint” — examining its structure, geography, symbolic design, textual history, and the ways modern scholarship reads its purpose and provenance.

A quick orientation: what Genesis 10 actually is

Genesis 10 presents the descendants of Noah’s three sons — Japheth, Ham, and Shem — and, through a succession of names, offers what the ancient Israelites (or the redactors who shaped the text) considered the peoples of the world. The chapter is often called the Table of Nations because it enumerates roughly seventy names of peoples, clans, and places — a number that in ancient Near Eastern and biblical symbolism commonly signified completeness or universality. As such, Genesis 10 is less a census than a compact ethnography: a representative map of “the nations” as understood by the biblical writers.

Structure as theology: three branches, seventy names

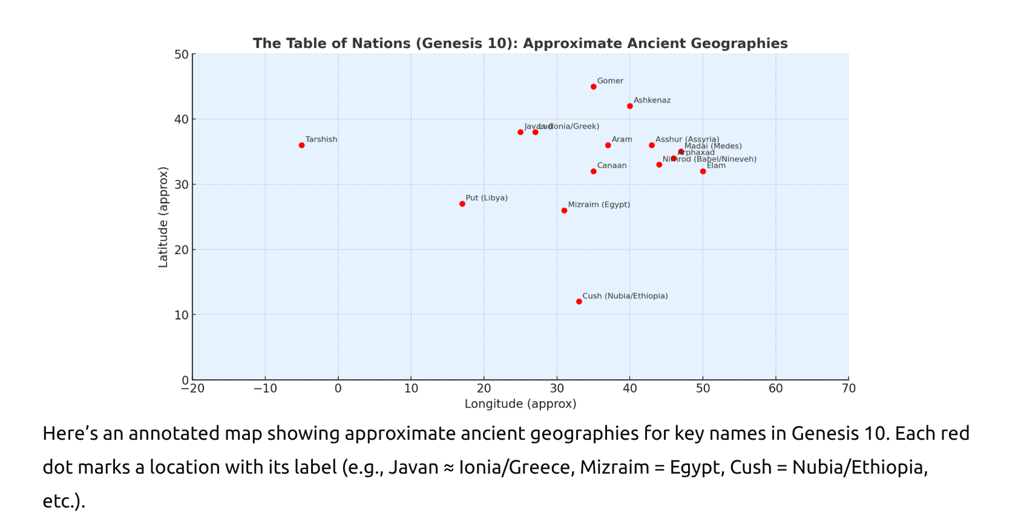

The layout is deliberate. The chapter is bracketed by identical framing formulas (“These are the generations of…” in 10:1 and 10:32) and divided according to the three sons of Noah, a triadic taxonomy that organizes peoples into northern, southern, and eastern–western zones. Japheth’s line is often associated with groups to the north and west (Anatolia, Greece, parts of the Mediterranean); Ham’s line clusters to the south and west (Egypt, parts of Africa, and Canaan); Shem’s line centers on the Near East and Mesopotamia, forming the ancestral background from which Israel emerges. The chapter’s internal order is unmistakably geographic as well as genealogical: it maps the horizon of the ancient Israelite world from the Nile and the Horn of Africa to the Anatolian and Ionian coasts and into south-west Iran.

The final number — seventy — matters. It is a symbolic round number that appears elsewhere in the biblical tradition (e.g., the 70 elders in Exodus; the seventy sent out in Luke). Genesis 10’s seventyfold list communicates totality: a theological statement that humanity, in all its diversity, is accounted for, ordered, and ultimately traceable to a shared covenantal history rooted in Noah.

Reading names as place-markers: ethnonyms and toponyms

Many of the chapter’s names are recognizable as ancient place-names or ethnic group labels, though identifying each with modern geography requires care. Some well-attested identifications:

Mizraim is the Hebrew name for Egypt; Cush generally denotes Nubia/Ethiopia; Put (Phut/Phut) is usually associated with Libya or parts of North Africa; Canaan denotes the Levantine coastal lands later associated with Israel’s neighbors.

Javan corresponds to the Greeks (Ionia), Madai to the Medes (in northwestern Iran), and Elam to the region east of Mesopotamia (southwest Iran). Ashkenaz, in some contexts, denotes groups north of the Levant (later medieval readings turned it into a marker for Europe, but in Genesis its immediate reference is to peoples in the north or northeast).

But not every name maps neatly to a single modern ethnicity, and the ancient scribes did not share our modern categories of race, language family, or nation-state. Some names likely represent clans or city-states no longer visible in the archaeological record; others are ethnonyms that have shifted meanings across centuries. The Table must therefore be read as a blend of living memory, interpretive etymology, and editorial arrangement rather than a literal modern ethnography.

Composition and editorial shape: layers and literary intent

Scholars long have argued that Genesis 10 is not a single, homogeneous composition but a compilation of traditions stitched into a theologically coherent list. Classic critical commentaries (Westermann, Wenham, Sarna among them) explain that certain verses — such as the Nimrod episode (vv. 8–12) — look like later insertions or narrative interpolations that interrupt the otherwise schematic genealogy. The chapter’s language exhibits formulaic genealogical markers similar to other ancient Near Eastern king-lists and genealogies, suggesting that the Hebrew authors were drawing on older models while reframing them for Israel’s theological purposes.

Why compile such a list? Several complementary answers appear in modern scholarship: (1) as a theological claim to the unity of humankind under the covenantal history that begins at Noah; (2) as an ideological map that places Israel within — and often above — the family of nations; (3) as an ethnographic memory that preserves knowledge of ancient migrations, trade routes, and political centers; and (4) as a rhetorical device that prepares the reader for the particularization of the Abrahamic promise in subsequent chapters. The Table thus functions as both a cosmological claim and a narrative hinge.

The Table and the ancient Near Eastern intellectual context

Genesis 10 did not emerge in a vacuum. Across the second and first millennia BCE, Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Levantine, and Egyptian texts produced their own king-lists, origin stories, and population registers. The idea of ordering humanity into groups, attaching divine patronage to nations, and using genealogies to explain political relationships is a regional intellectual practice. Scholars point to parallels — not direct borrowings — that help explain why the Hebrew author(s) fashioned a list of seventy nations: the number itself resonates with broader Near Eastern symbolic systems (e.g., Ugaritic and Mesopotamian lists of divine sons or tribal groupings). Genesis 10 refracts local knowledge through Israelite theology and narrative needs.

Deuteronomy 32:8, the Dead Sea Scrolls reading, and divine administration

Genesis 10’s cosmological ordering finds a curious echo in Deuteronomy 32:8–9, a passage whose textual history has received intensive scholarly attention. The Masoretic Text reads as if the Most High divided the nations according to the “sons of Israel,” but the Dead Sea Scrolls and some other ancient witnesses preserve a reading that better aligns with the mythological background: “according to the number of the sons of God” (a phrase linked to divine councils recorded in Ugaritic and Mesopotamian literature). Michael S. Heiser and other scholars argue that this variant reveals an ancient worldview in which a divine council or a set of subordinate divine beings presided over different nations — an idea that resonates with the Table’s portrayal of nations arranged and apportioned in an ordered cosmos. This textual variant highlights how Israelite monotheism reinterpreted older Near Eastern cosmological motifs.

Nimrod, urbanism, and the narrative kernel

One of the most arresting parts of Genesis 10 is the brief account of Nimrod (10:8–12): a “mighty hunter before the Lord” who establishes the first cities (Babel/Calneh, Nineveh, etc.). Nimrod is a narrative hotspot: his description interrupts genealogical formulae and points to the rise of early urban polities — the state-level societies and city-states whose artifacts and ruins scholars excavate in Mesopotamia and the Levant. Some scholars see in the Nimrod notice a memory-vestige of early urbanization and kingship: a compressed literary memory that names recognizable early cities and hints at the sociopolitical transformations that defined the Bronze Age world. Genesis 10 thus combines genealogical cataloguing with flashes of historical memory.

Purpose: theology, identity, and geopolitics

What was the point of the Table? The answer lies in the intersection of theology and identity politics. Genesis 10 establishes (1) a theological universalism — all nations are kin, sprung from Noah — and (2) a narrative particularism — the line of Shem (and within it, the later Abrahamic line) will be the locus of divine election. This double move legitimizes Israel’s special status without denying the reality or dignity of other peoples. At the same time, the Table provides practical geopolitical intelligence: it catalogs neighbors, enemies, trade partners, and distant lands, packaging geographical, ethnic, and political knowledge into theological prose. It is a map in words — an ideological cartography for a people whose survival and identity were bound up with knowing their world.

How modern readers have misused the Table

Because Genesis 10 links names to peoples, later interpreters in antiquity and in the modern era sometimes tried to force the chapter into rigid racial or scientific schemes. Medieval commentators and even early modern chronologers (e.g., Josephus) read the list as literal genealogy and tried to identify all modern nations with its names. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, some scholars used Genesis 10 to underpin racially tinged taxonomies; more recently, geneticists and popular writers have attempted to align genetic haplogroups with Genesis lineages. These efforts typically overstep the text’s genre and intention: the Table is theological-ethnographic, not a modern ethnology or genetic map. Responsible scholarship treats Genesis 10 as an ancient worldview that must be interpreted in its cultural and literary context rather than retrofitted to modern categories.

What archaeology and linguistics can confirm (and what they can’t)

Archaeology and historical linguistics can corroborate certain geographic pointers in Genesis 10: recognizable city-names and broad regional distributions (e.g., Egyptian/Mediterranean groups clustered with Ham, Ionian names in Japheth’s list, etc.). Excavations in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Egypt, and the Levant confirm the existence of the urban centers implied by the text and the connectivity of the ancient Near Eastern world during the Bronze Age and later periods. However, archaeology cannot validate genealogical descent claims or the chapter’s theological claims. Material culture does not produce the kind of genealogical proof Genesis 10 asserts; it does provide confirmatory context for migration corridors, trade routes, and the cultural prominence of listed centers. The most methodologically honest reading treats archaeology as a check on geographic and historical plausibility rather than a verification of biblical etiologies.

The Table in later religious and cultural imagination

Genesis 10 has had wide afterlife power. It informed Jewish and Christian exegetical traditions, shaped medieval ethnographies, influenced maps of the world synthesized by scholars and clerics, and provided raw material for theological reflection about the scope of God’s covenantal concern. Its seventy names furnished a template for later lists of the nations (and sometimes for polemics), but its deeper theological move — to assert both human commonality and Israel’s unique vocation — remained its enduring legacy in Judeo-Christian thought. Contemporary readers find here both a prophetic cosmopolitanism (a recognition of humanity’s unity) and an ancestral narrative that underscores Israel’s place in history.

Reading Genesis 10 today: responsible hermeneutics

Modern readers — scholars, pastors, and laypeople alike — face a responsibility when approaching the Table. A responsible hermeneutic attends to:

Genre: Genesis 10 is theological genealogy combined with ethnographic shorthand, not a modern history or scientific taxonomy. Internet Archive

Context: The list reflects ancient Near Eastern cognitive maps and theological concerns. It should be read in light of contemporaneous literatures and archaeological context.

Ethical implications: The Table has been used at times to justify racial or nationalist agendas; careful reading resists such instrumentalization and insists on its primary theological claim: common descent and shared humanity under God’s ordering.

Conclusion: an ancient blueprint that still speaks

The Table of Nations is a remark-able artifact: compact yet capacious, local yet global, genealogical yet geographical. It surveys the ancient world in a handful of verses, assigning place-names, ordering human diversity, and preparing the narrative stage on which the story of Israel — and the Bible’s ongoing conversation about God and the nations — will play out. For modern readers it is a reminder that ancient peoples attempted to make sense of diversity through story, order, and theological claim. Read on their own terms, these verses reveal an ancient blueprint for human identity: not a literal map of bloodlines, but a sacred cartography that declares both the kinship and the distinctiveness of the world’s peoples.

Selected sources and further reading

(These are the principal scholarly and accessible sources used in this article.)

John Day, “The Table of Nations: The Geography of the World in Genesis 10”, TheTorah.com — overview and geographic mapping of Genesis 10. TheTorah.com

Chapter “The Table of Nations” in Genesis, Brill (recent scholarly volume) — up-to-date scholarly discussion of structure, symbolism, and historical context. Brill

Claus Westermann, Genesis: A Commentary — classic critical commentary addressing literary structure and editorial layers. Internet Archive

Nahum M. Sarna, JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis — careful, conservative-critical Jewish commentary with helpful notes on identifications and tradition. Logos

Michael S. Heiser, “Deuteronomy 32:8 and the Sons of God” (Bibliotheca Sacra, 2001) — influential article on the Deuteronomy textual variant and the notion of divine allotment of nations. drmsh.com

Biblical Archaeology Review / Biblical Archaeology Society materials on the Table of Nations — accessible archaeological and contextual reflections.