“Not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us.” —Titus 3:5

In cities across the world, religious structures dominate skylines and calendars. Ritual observances mark weeks and seasons. Ethical codes shape communities. From ancient temples to modern megachurches, organized religion remains one of humanity’s most enduring institutions. It promises moral clarity, communal identity, and, in many traditions, a pathway to divine acceptance. Yet within the Christian Scriptures—particularly in the writings of the Apostle Paul—there emerges a sharp distinction between religion as a system of human effort and the person and work of Jesus Christ as the sole basis of salvation.

That distinction is summarized in Titus 3:5: “Not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us.” The verse does not criticize moral conduct itself; rather, it challenges the premise that human performance can secure reconciliation with God. For Paul, the dividing line between religion and Christ is not sincerity, discipline, or devotion. It is the source of righteousness.

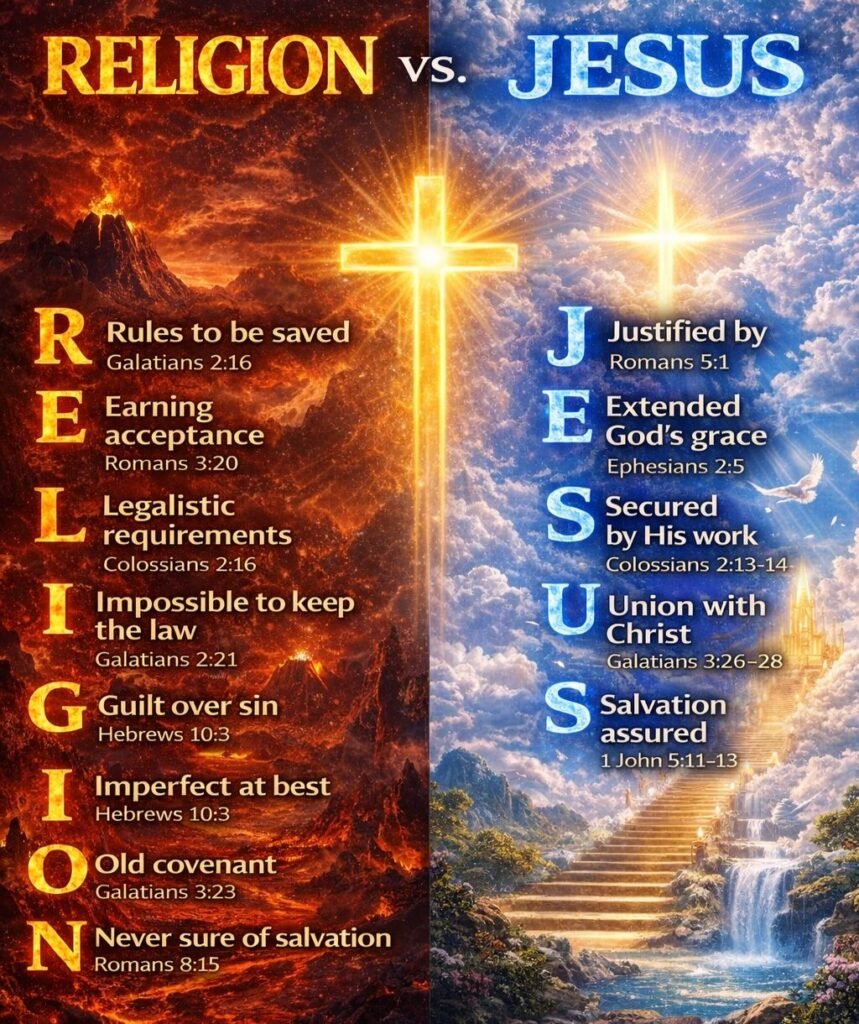

Religion, broadly defined, operates on the logic of attainment. Adherents are instructed to observe commandments, perform rituals, cultivate virtues, and avoid transgressions. Compliance may vary across traditions, but the structure remains recognizable: prescribed actions are linked to anticipated outcomes. The underlying assumption is that acceptance—whether by God, community, or conscience—can be achieved through adherence.

Paul’s letters confront that assumption directly. In Galatians 2:16, he writes, “Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ.” The context is crucial. Early Christian communities were debating whether Gentile believers must adopt Jewish legal observances to be fully accepted. Paul’s response was unequivocal. Justification—being declared righteous before God—does not arise from law-keeping. It rests on faith in Christ.

This was not a minor theological adjustment. It was a reorientation of the entire basis of religious confidence. If righteousness cannot be generated through compliance with divine commandments, then religion’s core mechanism is rendered insufficient. Paul reinforces the point in Romans 3:20: “By the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified in his sight.” The law, in his argument, reveals sin rather than remedies it. It functions diagnostically, not therapeutically.

Such claims were controversial in the first century and remain so today. Many religious systems depend upon structured observance to cultivate identity and moral discipline. Paul does not dismiss ethical living; he repeatedly calls believers to holiness. What he rejects is the notion that ethical living can erase guilt or establish merit before God. The distinction is subtle but decisive.

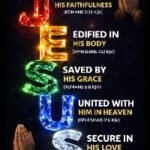

In modern discourse, the term “religion” can encompass a wide array of practices and beliefs. Within Pauline theology, however, the focus narrows to any attempt to secure divine favor through human effort. In Ephesians 2:8–9, Paul writes, “For by grace are ye saved through faith… not of works, lest any man should boast.” The exclusion of boasting is central. If salvation were attainable through effort, grounds for self-congratulation would remain. Grace, by definition, eliminates that possibility.

The contrast between effort and grace has existential implications. Religious striving often produces anxiety. The question lingers: Have I done enough? In Romans 10:3, Paul describes those who seek to “establish their own righteousness” rather than submit to God’s righteousness. The phrase suggests ongoing exertion without final assurance. Submission, in contrast, involves relinquishing self-generated claims in favor of divine provision.

This theme surfaces again in Colossians 2:13–14, where Paul speaks of sins being forgiven and the “handwriting of ordinances” taken out of the way, nailed to the cross. The imagery evokes cancellation of debt. Under religious systems centered on law, infractions accumulate as liabilities. In Paul’s presentation of the gospel, those liabilities are addressed not incrementally but definitively through Christ’s crucifixion.

Critics sometimes caricature this perspective as antinomian, suggesting that it encourages moral laxity. Paul anticipates such objections. In Romans 6:1–2, he asks, “Shall we continue in sin, that grace may abound? God forbid.” Grace does not trivialize wrongdoing; it transforms the basis of obedience. Instead of striving to earn acceptance, believers act from a position of acceptance already granted.

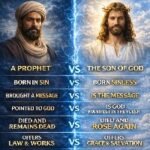

The historical setting of Paul’s ministry underscores the radical nature of his claims. First-century Judaism placed high value on Torah observance as covenant faithfulness. Greco-Roman religions likewise involved rituals aimed at appeasing deities. Against both backdrops, Paul proclaimed a message centered not on ritual compliance but on a crucified and risen Savior. In 1 Corinthians 15:1–4, he summarizes the gospel as the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ for sins. The emphasis rests on what Christ accomplished, not on what adherents must accomplish.

The psychological shift from performance to grace can be profound. Religion often measures progress through visible markers—attendance, offerings, fasting, pilgrimage, or moral discipline. Paul relocates the decisive event outside the believer’s activity. In Romans 5:1, he declares, “Therefore being justified by faith, we have peace with God.” Peace, in this context, signifies resolved hostility. It is not contingent upon fluctuating performance but grounded in a completed act.

Law and liberty form another axis of contrast in Pauline thought. In Galatians 5:1, he exhorts believers to “stand fast… in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free.” The letter addresses a community tempted to revert to legal observance as a means of spiritual security. Paul characterizes such regression as bondage. The law, though holy and just, exposes transgression without imparting power to overcome it. Liberty in Christ, by contrast, flows from the indwelling Spirit, described in Romans 8:2 as “the law of the Spirit of life.”

The language of liberty does not imply moral relativism. Paul consistently calls for conduct consistent with the gospel. Yet obedience is reframed as the fruit of new life rather than the prerequisite for acceptance. In 2 Corinthians 5:17, he states, “If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature.” The transformation is ontological, not merely behavioral. Religion may seek to modify conduct; Paul speaks of regeneration.

Guilt and conscience occupy significant space in religious experience. Repetitive rituals can function as temporary relief from moral burden, but they may also reinforce awareness of failure. The Epistle to the Hebrews, though not traditionally attributed to Paul in modern scholarship, articulates a similar concern about recurring sacrifices reminding worshipers of sin. Pauline letters echo this finality of forgiveness. In Colossians 2:13, he affirms that believers are forgiven “all trespasses.” The comprehensiveness of that claim distinguishes grace from systems that require continual atonement.

Another dividing line concerns mediation. Many religious traditions rely on intermediaries—priests, rituals, sacred spaces—to facilitate access to the divine. Paul acknowledges only one mediator in 1 Timothy 2:5: “the man Christ Jesus.” The exclusivity of this claim narrows the pathway to reconciliation. It challenges structures that place institutional authority between the individual and God. Salvation, in Pauline theology, is not dispensed through ritual performance but received through faith in a person.

Assurance represents perhaps the most pastoral dimension of the divide. In Romans 8:38–39, Paul expresses confidence that nothing “shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” The security described is comprehensive. Religion grounded in works often leaves adherents uncertain about final standing. Pauline assurance rests not on the constancy of human devotion but on the constancy of divine promise.

Sociologically, systems of religion can foster cohesion and moral accountability. Paul does not advocate anarchic spirituality detached from community. He writes to organized assemblies, instructs leaders, and addresses corporate worship. The distinction he draws is not between community and isolation, but between reliance on human systems for justification and reliance on Christ’s finished work.

The phrase “finished work” echoes Jesus’ declaration in the Gospel narratives, yet Paul elaborates its theological implications. If Christ’s death satisfied the demands of justice, then supplementary effort cannot enhance its efficacy. In Romans 11:6, Paul argues that grace and works are mutually exclusive as bases for salvation. To mix them is to compromise the definition of grace.

This exclusivity unsettles pluralistic sensibilities. In a world where religious diversity is often celebrated as equally valid, Paul’s insistence on Christ alone as sufficient can appear narrow. Yet from his perspective, the sufficiency of Christ magnifies divine mercy. If salvation depended on cumulative human effort, only the disciplined or privileged might hope to attain it. Grace democratizes access.

The ethical consequences of this theology are substantial. Freed from the pressure to earn favor, believers are called to serve out of gratitude. In Ephesians 2:10, immediately following the declaration of salvation by grace, Paul writes that believers are “created in Christ Jesus unto good works.” Works follow salvation as evidence, not as currency. The sequence preserves both moral seriousness and doctrinal clarity.

The experiential dimension of grace often manifests as rest. While Paul does not use that term as prominently as the author of Hebrews, the logic is present. If justification is settled, striving for acceptance ceases. The believer’s energy can be redirected toward love, generosity, and perseverance. Religion may motivate through fear of penalty; grace motivates through appreciation of mercy.

Yet the allure of performance-based righteousness persists. Human pride gravitates toward measurable accomplishment. Religious observance offers tangible metrics. Paul’s own background as a Pharisee illustrates the temptation. In Philippians 3:4–9, he recounts his former credentials and concludes that he counts them as loss “that I may win Christ.” The renunciation of self-derived status underscores the depth of the divide.

The implications extend beyond individual spirituality to ecclesial identity. Paul describes the church as the Body of Christ, formed not by shared ethnicity or adherence to ceremonial law, but by faith. In Ephesians 2:15, he speaks of Christ creating “in himself of twain one new man.” The unity achieved is not institutional uniformity but shared participation in grace. Religion often segregates through boundary markers; the gospel unites across them.

Contemporary religious landscapes frequently blend moral instruction with motivational rhetoric. Success, fulfillment, and purpose are presented as attainable through disciplined practice. Pauline doctrine challenges any framework that centers ultimate hope on human capacity. In 2 Corinthians 3:5, Paul states, “Not that we are sufficient of ourselves… but our sufficiency is of God.” Dependence replaces self-reliance.

The divide between religion and Jesus, as articulated by Paul, does not eliminate structure, community, or obedience. It relocates their foundation. The believer obeys because reconciliation has occurred, not in order to achieve it. The church gathers to celebrate grace, not to negotiate merit. Spiritual disciplines become expressions of relationship rather than transactions aimed at appeasing deity.

In evaluating this perspective, one must acknowledge its transformative potential. For individuals burdened by cycles of guilt and effort, the proclamation of unconditional mercy can be liberating. For institutions invested in maintaining control through regulation, it can be destabilizing. Paul himself faced opposition from those who perceived his message as threatening established order.

Ultimately, the distinction hinges on the identity and sufficiency of Jesus Christ. If He is, as Paul claims, the one through whom redemption is accomplished and righteousness imputed, then religion as a ladder to heaven becomes redundant. If, however, human effort contributes to justification, grace is diminished. Paul leaves little room for synthesis. “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to every one that believeth” (Romans 10:4).

The conversation continues across centuries, shaping theological debates and personal convictions. At its core lies a question of trust: will one rely on accumulated deeds or on divine mercy? In Paul’s presentation, the answer determines not only doctrinal alignment but eternal destiny. Religion may refine behavior and organize devotion. Jesus, in Pauline doctrine, reconciles sinners to God through grace alone.