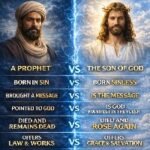

Debate over religious authority rarely centers on whether influential teachers have existed. History records many. The question that has persisted across centuries instead concerns verification. Which message, if any, carries divine authentication rather than human aspiration? Within the New Testament record, the earliest Christian communities grounded their answer not in philosophical coherence or ethical appeal but in a single claimed event: resurrection. The significance of Jesus of Nazareth, in this framework, is inseparable from the assertion that he did not remain dead. The earliest written explanations of that claim appear in the letters of the Apostle Paul, whose correspondence predates the later narrative Gospels and provides the first systematic interpretation of what the resurrection was understood to accomplish.

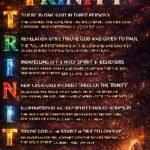

Paul did not present the Christian proclamation as the refinement of religious instinct. He described it as information disclosed to him rather than discovered by him. In his own account, the message he carried was received independently of human instruction. This assertion was controversial even in his own lifetime because it placed the origin of salvation outside philosophical reasoning and outside inherited tradition. He insisted that reconciliation between humanity and God depended on a historical act revealed by God rather than a path gradually discerned by moral reflection. The emphasis created a dividing line between religious exploration and revealed announcement. One depends on human ascent toward the divine; the other depends on a declaration coming from the divine toward humanity.

In the Greco-Roman world where Paul traveled, religious diversity was common. Temples dedicated to various deities coexisted within the same cities, and philosophical schools offered competing systems for ethical living. Paul’s approach did not attempt to harmonize these frameworks. Instead, he introduced a claim that bypassed them: forgiveness and eternal life were secured by the death and resurrection of a specific person. The credibility of the claim, he argued, rested on the public nature of the resurrection and the witnesses who encountered the risen Christ. The message therefore depended on testimony rather than speculation.

Paul’s explanation did not position Jesus merely as a teacher who clarified moral principles. Many traditions could supply moral instruction. What distinguished the Christian proclamation, according to Paul, was identity rather than advice. He described Jesus as embodying truth itself, not simply communicating it. The implication was that truth in this context referred to correspondence with divine reality rather than abstract correctness. If the resurrection occurred, then the person who rose possesses authority over life and death; if it did not occur, then the movement collapses into one philosophy among many.

The apostle’s letters repeatedly address the human tendency to seek acceptance through effort. He observed that communities often attempted to integrate the new message into familiar systems of obligation, adding rituals or moral prerequisites as conditions for security. Paul rejected that adaptation. He argued that human striving cannot produce righteousness because the problem being addressed is judicial rather than behavioral. Humanity’s condition, in his analysis, involves guilt before a divine standard, not merely ignorance requiring instruction. Therefore the solution must be legal satisfaction rather than ethical improvement.

This reasoning led Paul to interpret the death of Christ as substitutionary. Jesus’ execution under Roman authority was not viewed simply as martyrdom but as a transaction in which sin’s penalty was borne by another. The resurrection then functioned as confirmation that the payment was accepted. If death is the consequence of sin and Christ rose, the penalty has been exhausted. The result, Paul maintained, is justification granted to those who trust that event rather than their own performance.

The uniqueness of the claim depends heavily on the finality of death. Every religious founder eventually dies; their teachings continue through followers. The Christian proclamation reverses the pattern: the central figure’s continued life validates the teaching itself. Paul emphasized that if Christ remained in the grave, faith would be futile. His argument therefore tied the entire structure of salvation to a verifiable historical assertion rather than to enduring moral wisdom.

Paul also addressed access to God. Traditional religious systems often depend on intermediaries such as priests, sacrifices, or ritual observances. Paul asserted that mediation is concentrated in a single person. Because Christ’s death addressed sin and his resurrection established ongoing life, believers approach God through him directly. The need for repeated sacrificial structures disappears in this model because the necessary reconciliation has already occurred. This claim dramatically altered religious practice among early Christian communities, replacing temple-centered ritual with gatherings focused on teaching and remembrance.

A significant portion of Paul’s correspondence explains why this message spread beyond the boundaries of Israel. Earlier scriptures contained promises connected to a national covenant, but Paul described a newly disclosed arrangement in which Gentiles participate equally without adopting Israel’s law. He referred to this inclusion as a mystery now revealed. The resurrection, in his explanation, created a new community defined by faith rather than ethnicity. Christ became the unifying head of this multinational body, and the basis of membership was belief in the announced gospel rather than adherence to ancestral customs.

Paul summarized that gospel with consistent brevity: Christ died for sins, was buried, and rose again. He presented these points not as symbolic but as factual occurrences carrying doctrinal meaning. Death addressed guilt, burial confirmed reality, and resurrection demonstrated victory over death. Faith in this sequence resulted in salvation because it relied on a completed accomplishment rather than anticipated human improvement.

His insistence on faith alone generated resistance from both religious and philosophical audiences. Moralists objected that removing performance requirements encouraged irresponsibility. Paul countered that genuine transformation arises from new identity rather than fear of penalty. According to his explanation, believers receive the Spirit of God, producing internal change rather than external compliance alone. Obedience therefore follows acceptance instead of earning it.

The apostle also addressed certainty. Many religious traditions maintain uncertainty about final standing, leaving adherents hoping their efforts suffice. Paul argued that the resurrection establishes assurance because the decisive judgment already occurred at the cross. If Christ bore condemnation, believers cannot later face it. Eternal life becomes a present possession rather than a future possibility. This assurance was not presented as psychological comfort but as logical consequence of the completed transaction.

The early Christian proclamation therefore rested on several interconnected claims: a historical resurrection, substitutionary atonement, universal accessibility, and assurance through faith. Remove any element and the structure changes fundamentally. Without resurrection, Christ becomes another teacher. Without substitution, salvation becomes self-improvement. Without universal scope, the message returns to ethnic limitation. Without assurance, grace becomes probation.

Paul’s writings also shaped how believers understood mortality. Death remained a physical reality, yet its significance changed. Because Christ rose, death no longer determined ultimate destiny. Paul described it as an enemy already defeated, awaiting final removal. This perspective allowed early Christians to endure persecution with unusual confidence. Their hope depended not on social survival but on participation in Christ’s life beyond death.

The social implications were considerable. Communities composed of diverse backgrounds gathered on equal footing, sharing meals and resources. Status distinctions common in surrounding culture weakened because standing before God derived from faith alone. The resurrection, therefore, influenced not only theology but communal behavior. It created an identity transcending nationality and class.

Paul also confronted rival interpretations that attempted to incorporate Christ into broader philosophical systems. Some teachers portrayed him as one spiritual intermediary among many. Paul rejected such pluralism, arguing that reconciliation requires a mediator who has dealt decisively with sin. Because the resurrection demonstrated victory over death itself, no comparable mediator remained necessary or possible. The exclusivity was not presented as sectarian preference but as logical outcome of the event’s significance.

His emphasis on grace distinguished the Christian message from performance-based spirituality. Grace, in Paul’s vocabulary, referred to unearned favor granted because of Christ’s work. It did not function as leniency toward continued guilt but as recognition that guilt had been addressed. The believer’s role was trust rather than contribution. Ethical living followed as response, not prerequisite.

Over time, the Pauline interpretation became central to Christian theology. Later writers elaborated its implications, but the core remained: salvation depends on the risen Christ alone. Historical study indicates that this conviction motivated missionary expansion across the Mediterranean world. Converts were not asked to master philosophical systems but to believe a proclamation concerning a person and his resurrection.

Modern discussions often approach religion through comparative ethics or cultural impact. The earliest Christian documents, however, frame the issue differently. They present a testable claim about an empty tomb and its consequences. If accurate, it redefines humanity’s relationship with God; if inaccurate, it dissolves into legend. Paul acknowledged this binary outcome openly, stating that faith stands or falls with the resurrection.

The enduring relevance of his message lies in its clarity. It does not offer multiple paths converging on the same goal but one event producing a specific result. Forgiveness, reconciliation, and eternal life are said to be secured through Christ’s death and confirmed through his resurrection. Human effort neither initiates nor completes the process. Faith accepts what has been accomplished.

This perspective explains why early Christians centered their gatherings on proclamation rather than ritual repetition. The essential act had already occurred; the community existed to announce it. Teaching aimed to clarify implications rather than replicate sacrifice. The focus remained consistently on the risen redeemer whose identity defined the movement.

Across centuries, interpretations have varied, yet the earliest articulation preserved in Paul’s letters continues to shape the core of Christian belief. The claim remains straightforward: salvation rests on the historical death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and no alternative foundation offers the same assurance. For Paul and those influenced by him, this was not one option among many but the decisive act through which God reconciled humanity to himself.