The Unity of the Godhead Revealed and Applied in the Dispensation of Grace

John 10:30 (KJV)

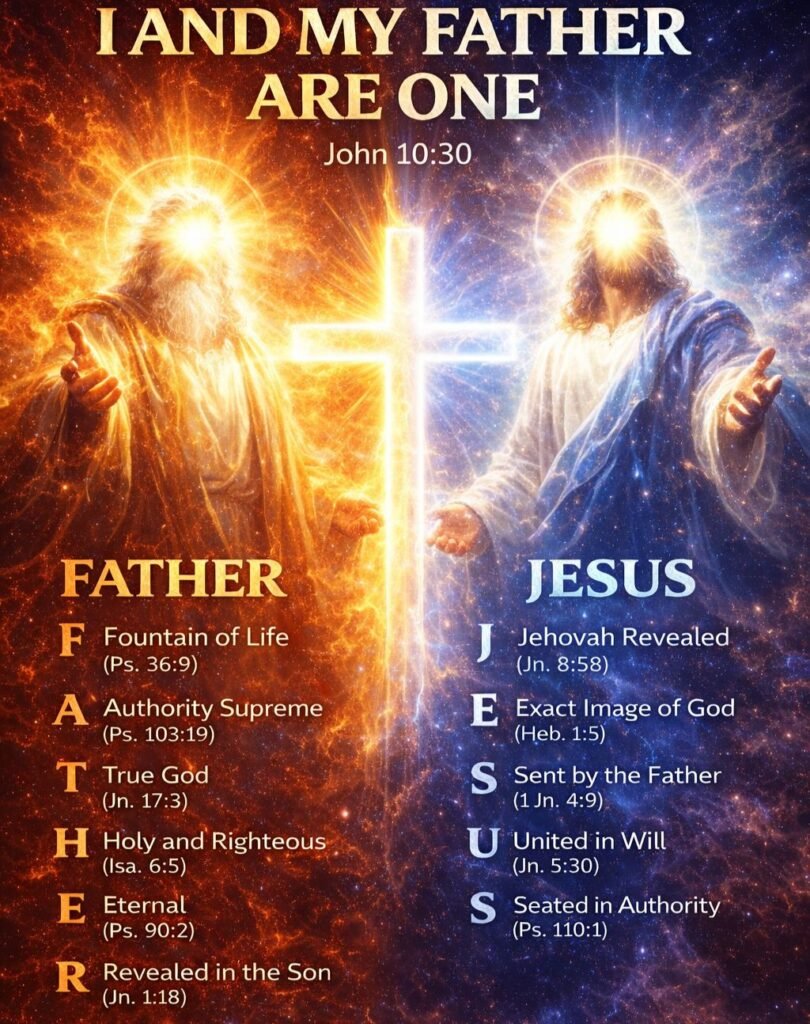

In the tenth chapter of the Gospel of John, Jesus utters a sentence that has reverberated through two millennia of theological debate: “I and my Father are one” (John 10:30, KJV). The reaction is immediate and volatile. According to the narrative, those listening take up stones, prepared to execute Him for blasphemy. Their explanation is explicit: “because that thou, being a man, makest thyself God” (John 10:33). The response of His audience indicates they did not interpret His words as metaphorical. They understood the claim to be a direct assertion of divine identity.

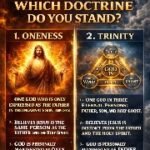

The statement remains one of the most contested lines in the New Testament. It stands at the center of discussions about the nature of Christ, the unity within the Godhead, and the coherence of Christian monotheism. Within a Pauline framework—particularly as understood in dispensational theology—the declaration carries implications not only for Christology but for soteriology, ecclesiology, and the believer’s present standing before God.

The claim of unity between the Son and the Father cannot be reduced to mere agreement of purpose. While harmony of will is certainly present in the New Testament record, the language of John 10:30 reaches further. The immediate context emphasizes divine authority. Jesus has just spoken of granting eternal life and of securing His sheep in a manner no external force can overturn. He places His protective authority alongside that of the Father. The security of believers rests upon a shared power that no adversary can overcome.

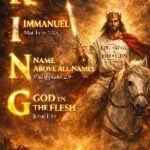

Paul’s letters, written later in the first century, provide doctrinal exposition that illuminates this unity. In Colossians 2:9, he states that “in him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily.” The assertion is comprehensive. The fullness of deity is not partially distributed or symbolically represented; it resides in Christ. This language eliminates the possibility that Jesus is a lesser or derivative divine being. The divine essence is not divided between Father and Son; it is shared.

The early church grappled with how to articulate this shared essence without collapsing into either polytheism or modalism. Paul’s writings, while not employing later creedal terminology, consistently maintain both distinction and equality. In Philippians 2:6, Christ is described as being “in the form of God” and as not considering equality with God something to be grasped or exploited. The passage presupposes equality prior to incarnation. The humiliation that follows does not negate divine status; it reveals voluntary condescension.

Hebrews 1:3, though not authored by Paul according to most scholars, aligns with Pauline theology in describing the Son as “the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person.” The term translated “express image” conveys exact representation. The Son is not a faded reflection; He is the precise imprint of the Father’s nature. Such language supports the interpretation that unity encompasses shared substance.

This ontological unity undergirds the New Testament’s presentation of sovereignty. Jesus speaks in John 5:22 of the Father committing all judgment to the Son. Authority is not transferred to an inferior agent; it is exercised by one who shares divine prerogative. In Ephesians 1:11, Paul writes of God working “all things after the counsel of his own will.” The singularity of counsel suggests no internal conflict within the Godhead. The will executed through Christ is not independent of the Father; it is the unified outworking of a single divine purpose.

Within dispensational theology, this unified will unfolds through distinct administrative periods. The current dispensation of grace, often associated with Paul’s apostleship to the Gentiles, does not introduce a new deity or a revised divine character. It reveals the same God acting according to a previously hidden aspect of His redemptive plan. Colossians 1:25–26 refers to a “mystery” that had been kept secret but is now made manifest. The revelation of the Body of Christ does not alter the unity between Father and Son; it displays it in new dimensions.

The incarnation represents a critical point of intersection between eternal unity and temporal history. John 1:18 declares that no man has seen God at any time, but the only begotten Son has declared Him. The invisible God becomes known through the visible Christ. Paul echoes this in 2 Corinthians 4:6, where he speaks of the light of the knowledge of the glory of God shining “in the face of Jesus Christ.” To encounter Christ is to encounter the self-disclosure of the Father.

The unity asserted in John 10:30 also bears directly on the question of salvation. In the immediate context, Jesus promises eternal life to His sheep and states that no one can pluck them from His hand. He then adds that no one can pluck them from the Father’s hand. The parallel construction implies coordinated preservation. Security is not divided between two competing powers; it is guaranteed by a unified divine grip.

Paul develops the theme of security in Romans 8. After declaring that there is “no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1), he proceeds to describe a chain of divine actions—foreknowledge, predestination, calling, justification, glorification—that originates in God’s purpose and culminates in assured glory. The chapter concludes with the affirmation that nothing can separate believers from the love of God in Christ. The basis of assurance is not human consistency but divine constancy.

The role of the Spirit further demonstrates coordinated operation within the Godhead. Ephesians 1:13 describes believers as sealed with the Holy Spirit of promise after trusting the gospel. The sealing is an act of divine authentication and preservation. The Father plans, the Son redeems, and the Spirit seals. Distinct roles are evident, yet the work is singular in intention and effect. The unity of Father and Son is not abstract theology; it is experienced in the believer’s salvation.

Critics of Trinitarian doctrine have argued that statements like John 10:30 merely express agreement in mission. However, the reaction of Jesus’ contemporaries suggests they perceived a deeper claim. Moreover, the broader Johannine context reinforces this reading. In John 17:5, Jesus speaks of glory shared with the Father before the world existed. Pre-existent shared glory implies more than functional alignment; it indicates shared divine identity.

Pauline theology does not treat Christ as a secondary divine agent acting independently. In 1 Corinthians 8:6, Paul reaffirms monotheism while distinguishing roles: “to us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all things… and one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things.” Creation itself is attributed to Christ as mediating agent. The structure preserves both unity and distinction. The Lord through whom all things exist cannot be a creature within the created order.

The resurrection provides further confirmation of unity and deity. Romans 1:4 describes Jesus as declared to be the Son of God with power by the resurrection. The event is not merely resuscitation; it is divine vindication. The Father raises the Son, yet Jesus also speaks of laying down His life and taking it again (John 10:18). The shared participation in resurrection power reflects shared authority.

In the present age, Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Psalm 110:1, frequently cited in the New Testament, portrays the Lord inviting another Lord to sit at His right hand until enemies are subdued. Paul applies this imagery in Ephesians 1:20–22, describing Christ as far above all principality and power. The seating at the right hand signifies co-regency and delegated authority consistent with shared sovereignty. It is not a temporary trial arrangement but an expression of exalted status.

For the Body of Christ, this exaltation has practical implications. Ephesians 2:6 states that believers are seated together in heavenly places in Christ. The language is positional rather than experiential. While physically present on earth, believers are regarded as participating in Christ’s exalted standing. Such a position would be impossible if Christ were not fully divine. Participation in His status presupposes the sufficiency and stability of His person.

Adoption into God’s family further illustrates applied unity. Galatians 4:6 notes that because believers are sons, God has sent forth the Spirit of His Son into their hearts, crying, “Abba, Father.” The relational intimacy made possible through redemption is grounded in the shared nature of Father and Son. The believer approaches God not through a distant intermediary but through union with One who shares the Father’s essence.

The unity of Father and Son also informs Christian worship. In John 5:23, Jesus declares that all men should honor the Son even as they honor the Father. Equal honor presupposes equal status. Paul echoes this trajectory in Philippians 2:11, where every tongue confesses that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. The glorification of the Son does not diminish the Father; it magnifies Him. Divine unity ensures that worship directed to Christ is not misdirected devotion.

Doctrinal clarity about Christ’s identity shapes ethical life. Colossians 2:6–7 urges believers to walk in Christ as they have received Him, rooted and built up in Him. The exhortation assumes that understanding who Christ is affects how believers live. If He is fully God, allegiance to Him is not optional. It defines loyalty, morality, and mission.

Paul’s role as apostle to the Gentiles emphasizes revelation tailored to the current dispensation. Yet his Christology is consistent with the Gospel accounts. The mystery revealed through him does not redefine Jesus; it expands understanding of how His person and work relate to a newly formed Body composed of Jew and Gentile without distinction. Unity within the Godhead becomes the foundation for unity within the church. First Corinthians 12:13 states that by one Spirit believers are baptized into one body. The source of ecclesial unity is divine unity.

The investigative question of application remains pressing. If Father and Son are one in essence and purpose, what does that mean for contemporary faith communities? It means that doctrinal deviation concerning Christ’s nature undermines the very basis of salvation. A diminished Christ cannot provide complete redemption. A divided deity cannot guarantee security. The coherence of the gospel depends upon the coherence of the Godhead.

The historical record shows that debates about Christ’s identity have often corresponded with broader cultural shifts. In periods where rationalism dominates, supernatural claims are softened. In eras marked by pluralism, exclusive assertions of deity are reframed as symbolic. Yet the New Testament text resists dilution. The unity claimed in John 10:30 is affirmed in contexts of controversy and cost.

Paul’s ministry frequently encountered opposition rooted in misunderstandings about Christ. In Colossae, philosophical speculation threatened to reduce Him to one spiritual power among many. Paul’s response was not compromise but clarification: Christ is the head of all principality and power (Colossians 2:10). The sufficiency of believers in Him depends upon His supremacy.

The forward-looking dimension of unity appears in eschatological passages. First Corinthians 15 outlines a sequence culminating in the Son delivering up the kingdom to the Father, that God may be all in all. Some have interpreted this as subordination in essence. However, within Pauline thought, the passage reflects functional order within a shared divine nature. The Son’s mediatorial role reaches completion, yet the unity of the Godhead remains intact.

The present proclamation of the gospel invites trust in this unified divine action. Romans 10:9 connects confession of Jesus as Lord with belief in His resurrection. The confession acknowledges both authority and identity. It is not a mere acknowledgment of moral leadership; it is recognition of divine lordship.

Transformation follows belief. Titus 2:11–12 teaches that the grace of God instructs believers to live soberly and righteously. The grace that saves originates in the unified purpose of Father and Son. Ethical change is not self-generated reform; it is response to revealed truth. Doctrine shapes devotion.

The continuity between the Gospels and Pauline epistles demonstrates that the unity of Father and Son is not an isolated Johannine theme. It permeates apostolic teaching. The God who planned redemption is the God who accomplished it in Christ and applies it through the Spirit. The believer’s standing is secured by coordinated divine action.

In contemporary discourse, assertions of exclusive divine identity can appear divisive. However, the New Testament presents clarity as a form of love. To obscure Christ’s identity is to obscure the means of salvation. The investigative assessment must therefore weigh not cultural comfort but textual fidelity.

The unity declared in John 10:30 remains foundational. It supports monotheism while explaining incarnation. It preserves distinction without division. It grounds security without fostering complacency. It invites worship without compromising reason.

In the dispensation of grace, believers do not speculate about the nature of God; they rely on revealed testimony. That testimony consistently presents Jesus Christ as fully sharing the Father’s essence, will, and authority. The implications extend beyond academic theology. They shape assurance, identity, mission, and hope.

The New Testament closes not with philosophical abstraction but with worship directed to the Lamb who shares the throne. The unity of Father and Son is not a peripheral doctrine. It is the architecture upon which the gospel rests.

The declaration “I and my Father are one” continues to demand response. It confronts skepticism, challenges complacency, and comforts faith. Within Pauline doctrine, it explains how redemption can be both gracious and just, how believers can be secure, and how worship can be rightly directed.

The coherence of Christian faith depends upon the coherence of its central claim: that in Jesus Christ, the fullness of deity dwells bodily, and that this Christ stands eternally united with the Father. From that unity flows salvation, security, and the formation of a unified Body composed of those who believe.

In the present era, the invitation remains open. Trust in the revealed Son results in reconciliation with the Father. Stand on the doctrine that has been delivered. Renew the mind according to apostolic teaching. Rest in the assurance secured by divine unity. Proclaim Christ with clarity, knowing that honoring the Son honors the Father who sent Him.

The investigative conclusion is straightforward. The statement in John 10:30 is neither poetic exaggeration nor theological afterthought. It is a declaration of shared essence and unified purpose within the Godhead. In the dispensation of grace, this unity forms the bedrock of Christian doctrine and the guarantee of eternal hope.