𝗛𝗢𝗪 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗛𝗢𝗟𝗬 𝗕𝗜𝗕𝗟𝗘 𝗖𝗔𝗠𝗘 𝗧𝗢 𝗕𝗘: 𝗛𝗜𝗦𝗧𝗢𝗥𝗬, 𝗗𝗘𝗕𝗔𝗧𝗘𝗦, 𝗔𝗡𝗗 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗦𝗛𝗔𝗣𝗜𝗡𝗚 𝗢𝗙 𝗔 𝗦𝗔𝗖𝗥𝗘𝗗 𝗧𝗘𝗫𝗧

𝗛𝗢𝗪 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗛𝗢𝗟𝗬 𝗕𝗜𝗕𝗟𝗘 𝗖𝗔𝗠𝗘 𝗧𝗢 𝗕𝗘: 𝗛𝗜𝗦𝗧𝗢𝗥𝗬, 𝗗𝗘𝗕𝗔𝗧𝗘𝗦, 𝗔𝗡𝗗 𝗧𝗛𝗘 𝗦𝗛𝗔𝗣𝗜𝗡𝗚 𝗢𝗙 𝗔 𝗦𝗔𝗖𝗥𝗘𝗗 𝗧𝗘𝗫𝗧

GOSPEL AND SPIRITUALITY

MrTruth.Tv

12/9/20256 min read

How the Holy Bible Came to Be: History, Debates, and the Shaping of a Sacred Text

Few books have shaped human civilization as profoundly as the Bible. It has inspired art, underpinned legal systems, fueled reformations, and divided communities. It has been carried into battle, used in political speeches, and placed in hotel nightstands around the world. For billions, it is God’s Word; for others, it is a cultural cornerstone or historical artifact.

But how did this collection of ancient writings become the Bible we know today? The journey from oral storytelling to bound volume spans more than a millennium and is filled with debates, revisions, and controversies. Understanding this story requires not only faith but also history, archaeology, and scholarship.

This article takes a deep look at how the Bible came to be: its origins, its transmission, its canonization, and the debates that continue to surround it.

The World Before the Bible

Long before the word “Bible” existed, ancient peoples in the Near East preserved their history, laws, and myths through oral tradition. Like their Mesopotamian neighbors—who gave us the Epic of Gilgamesh—the Israelites sang stories, recited genealogies, and preserved their identity through memory.

The earliest Israelite traditions likely circulated as songs or poetic narratives. For instance, scholars believe the Song of Deborah (Judges 5) is one of the oldest biblical passages, possibly dating to the 12th century BCE. Oral tradition allowed communities to pass knowledge across generations before literacy was widespread.

But oral tradition has limits: exile, war, and cultural blending threatened memory. The push to preserve traditions in writing came in times of crisis.

From Oral Tradition to Written Scripture

The earliest biblical texts likely appeared during Israel’s monarchy (10th–8th centuries BCE). Under kings like David and Solomon, scribes began recording royal annals, laws, and temple rituals. Later, during the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah, prophetic oracles and historical records were committed to writing.

A turning point came with the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE. Jerusalem’s destruction and the exile of its elites created a fear that Israel’s identity would vanish. In response, scribes compiled, edited, and preserved their traditions. The exile provided the crucible in which much of the Hebrew Bible was forged.

Scholars often refer to the Documentary Hypothesis—a theory that the Torah (Genesis–Deuteronomy) was woven together from four main sources:

J (Yahwist) – a southern tradition, portraying God in human-like terms.

E (Elohist) – a northern tradition, emphasizing prophecy and morality.

D (Deuteronomist) – linked to the religious reforms of King Josiah (7th century BCE).

P (Priestly) – a post-exilic strand stressing ritual, genealogy, and law.

While the specifics are debated, most scholars agree the Torah was compiled over centuries, finalized sometime in the Persian or early Hellenistic period (5th–3rd century BCE).

The Hebrew Bible: Defining the Canon

The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, is not a single book but a library divided into three sections:

Torah (Law) – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy.

Nevi’im (Prophets) – historical books like Joshua and Kings, plus prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah.

Ketuvim (Writings) – Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Daniel, Esther, and others.

The process of canonization was gradual. By the 2nd century BCE, most texts were recognized, but debates lingered. For example:

Esther faced resistance because it never mentions God explicitly.

Ecclesiastes was controversial for its skeptical tone.

Daniel, written in the 2nd century BCE, was among the last accepted.

The final canon was not firmly settled until the late 1st or early 2nd century CE, after the destruction of the Second Temple.

The Septuagint: A Greek Bible for a Greek World

As Jews spread across the Mediterranean, many no longer spoke Hebrew. In Alexandria, Egypt, Jewish scholars translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek around the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE. This translation became known as the Septuagint (from the legend of seventy translators working in unison).

The Septuagint contained books not found in the Hebrew Bible—such as Tobit, Judith, and 1–2 Maccabees. These “extra” books later became a dividing line between Christian traditions.

For early Christians, the Septuagint was the Bible. The New Testament writers quoted it extensively. Sometimes their quotations differ significantly from the Hebrew version, leading to textual puzzles for later readers.

The Birth of the New Testament

The story of the New Testament begins not with the Gospels, but with letters. The Apostle Paul, writing between 50–60 CE, produced epistles that circulated widely among early Christian communities. His letters to the Corinthians, Romans, and Galatians are among the earliest Christian documents we possess.

The Gospels came later:

Mark (~70 CE), widely seen as the earliest.

Matthew and Luke (80–90 CE), which expand on Mark and add unique traditions.

John (~90–100 CE), the most theologically distinct.

Other writings—Acts, pastoral letters, and apocalyptic visions like Revelation—rounded out the body of early Christian literature. But the early church produced far more texts than the 27 that made it into the New Testament.

The Struggle for a Christian Canon

Which books belonged in the New Testament was hotly debated for centuries.

In the 2nd century, the teacher Marcion created a radical canon excluding the Old Testament and trimming the New Testament to Luke and some Pauline letters. His views forced mainstream Christians to clarify their own standards.

The Muratorian Fragment (~170 CE) gives us the earliest surviving list of New Testament writings. By the 4th century, consensus had grown, with figures like Athanasius of Alexandria naming the 27 books we recognize today. Church councils at Hippo (393) and Carthage (397) confirmed the list.

Still, some books—like Revelation, Hebrews, and James—remained disputed for centuries, especially in the Eastern Church.

Transmission and Translation: The Bible Goes Global

Once canonized, the Bible spread through translation. In the West, St. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (late 4th century) became the standard for over a thousand years. In the East, translations into Syriac (Peshitta), Coptic, and Armenian flourished.

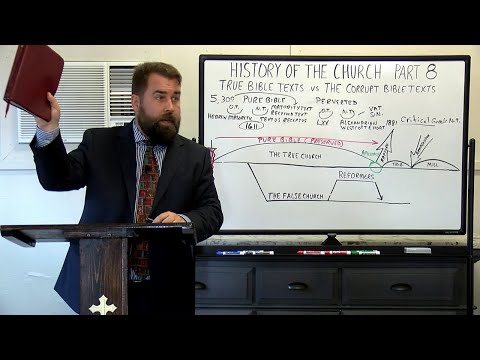

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century changed everything. Suddenly, Bibles could be mass-produced. Martin Luther’s German translation (1522–1534) and the English King James Bible (1611) brought Scripture to the common people and transformed language and culture.

The Apocrypha: Books in Dispute

One of the longest-running debates concerns the “Apocrypha” or “Deuterocanonical” books—texts included in the Septuagint but absent from the Hebrew Bible. Catholic and Orthodox traditions include them, while Protestants, following Luther, rejected them.

Thus:

A Catholic Bible has 73 books.

A Protestant Bible has 66.

Orthodox Bibles may contain even more, depending on tradition.

This debate illustrates that the Bible is not a monolithic text but a collection shaped by theological and historical choices.

Archaeology and Modern Discoveries

Modern archaeology has revolutionized biblical studies. The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in 1947, revealed ancient Hebrew manuscripts from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE. These texts demonstrated that multiple versions of biblical books circulated simultaneously, challenging earlier assumptions about a fixed text.

Other discoveries—like the Nag Hammadi library of Gnostic texts (1945)—show that early Christianity was far more diverse than the canon suggests.

The Bible in the Modern World: Faith and Debate

Today, the Bible continues to inspire devotion and scholarship, but also debate. Among the key issues:

Authorship: Did Moses write the Pentateuch? Did Paul write all the letters attributed to him? Scholars and traditions disagree.

Textual Authority: Should the canon be considered closed, or can other ancient texts offer insight?

Translation: Debates rage over “word-for-word” vs. “thought-for-thought” translations, and whether inclusive language should be used.

Archaeological Context: How much of the Bible is history versus theology? Discoveries often confirm but sometimes challenge biblical narratives.

For believers, the Bible remains inspired and authoritative. For historians, it is also a human artifact shaped by centuries of cultural, political, and theological struggle.

Conclusion: A Sacred Library, Not a Single Book

The Bible did not fall from heaven bound in leather. It is the product of centuries of storytelling, editing, translation, and debate. It emerged from exile and empire, from Jewish scribes and Christian apostles, from councils and controversies.

It is less a single book than a library of voices, testifying to the struggles of communities seeking God in history. And it is precisely this layered, debated, and living quality that has allowed the Bible to endure—shaping civilizations, sparking reformations, and continuing to guide faith and imagination into the 21st century.

References

Finkelstein, Israel & Silberman, Neil. The Bible Unearthed. New York: Free Press, 2001.

Hallo, William W. Origins: The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Brill, 1996.

Friedman, Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? HarperOne, 1997.

Barton, John. A History of the Bible: The Story of the World’s Most Influential Book. Penguin, 2019.

Josephus, Against Apion I.8.

Wright, N. T. The New Testament and the People of God. Fortress Press, 1992.

Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament. Yale University Press, 1997.

Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels. Vintage, 1979.

Trobisch, David. The First Edition of the New Testament. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Athanasius, Festal Letter 39 (367 CE).

Bruce, F. F. The Canon of Scripture. InterVarsity Press, 1988.

Jerome, Preface to the Pentateuch.

McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible. Anchor, 2002.

Metzger, Bruce M. An Introduction to the Apocrypha. Oxford University Press, 1977.

Vermes, Geza. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Penguin, 2012.

Robinson, James M. (ed.). The Nag Hammadi Library in English. HarperOne, 1990.

Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press, 2018.

Ryken, Leland. The Word of God in English: Criteria for Excellence in Bible Translation. Crossway, 2002.