Genesis 10:1–32 — The Table of Nations

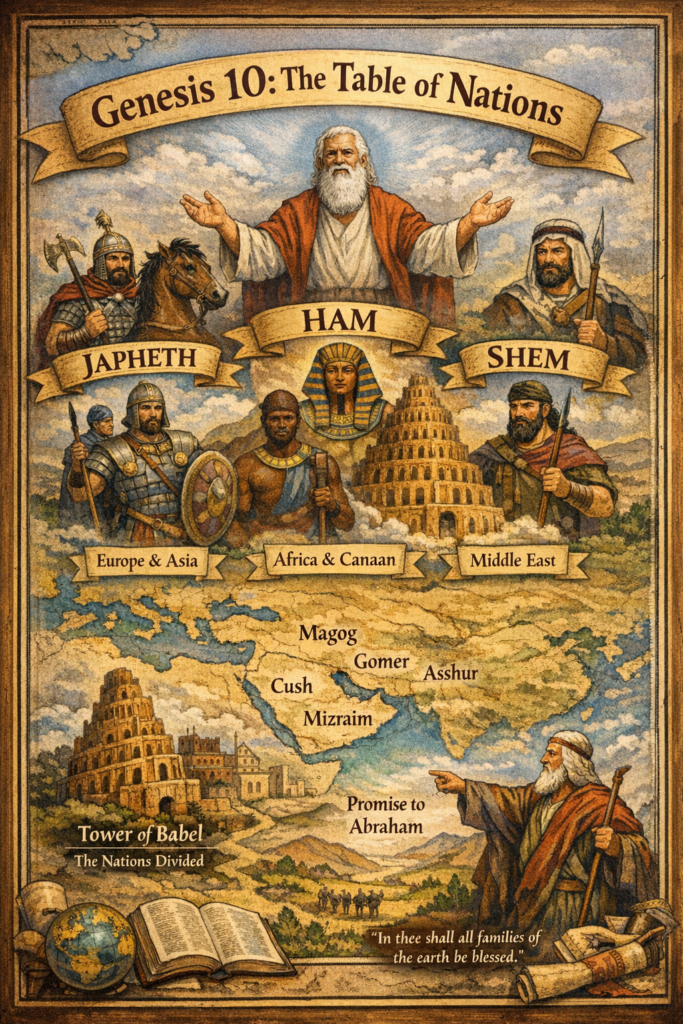

Genesis 10 stands as one of the most remarkable chapters in the Bible. At first glance, it appears to be little more than an ancient genealogy—a long list of names descending from the three sons of Noah after the Flood. Yet within those thirty-two verses lies what is often called “The Table of Nations,” a foundational passage that attempts to explain the origin and distribution of the world’s peoples. Far from being a mere list, it functions as a theological bridge between the Flood narrative in Genesis 6–9 and the account of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11. It offers not only a map of humanity’s expansion, but also a framework for understanding divine sovereignty, human unity, and the historical claims of Scripture.

This chapter identifies seventy primary nations descending from Shem, Ham, and Japheth. In Jewish tradition, the number seventy became symbolic of the totality of the Gentile world. Genesis 10, therefore, is not simply genealogical—it is programmatic. It tells the reader that all humanity after the Flood comes from one family. It anchors the biblical worldview in the idea of a shared ancestry while also explaining the diversity of languages, lands, and peoples.

The significance of the Table of Nations can be examined from multiple angles: theological, historical, and interpretive. It also carries particular weight in conservative evangelical circles, especially among teachers who emphasize the literal authority of the King James Bible and the historical reliability of Genesis.

The Purpose and Importance of the Table of Nations

Genesis 10 begins with the words: “Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and unto them were sons born after the flood.” This phrase “these are the generations” signals a structural division in Genesis. It marks a transition from judgment to expansion. Humanity has survived divine judgment through Noah’s ark, and now the earth begins again.

The Table of Nations matters for several key reasons.

First, it establishes that all post-Flood humanity descends from one righteous remnant. This reinforces the biblical theme of God preserving a seed through whom His purposes will continue. Just as Adam was the father of all before the Flood, Noah becomes the father of all afterward. The unity of the human race is a central theological claim here. Scripture does not present separate origins for different ethnic groups. All nations share one source.

Second, Genesis 10 provides an early biblical geography. It describes how the descendants of Noah spread “after their families, after their tongues, in their lands, after their nations.” These repeated phrases emphasize territorial and linguistic development. This chapter anticipates the confusion of languages in Genesis 11, but it presents the nations in an organized, structured manner before describing how languages were divided at Babel. Chronologically, Genesis 11 explains how the dispersion occurred; Genesis 10 catalogues the results.

Third, it demonstrates God’s sovereignty over history. The nations are not accidental developments. They unfold according to divine providence. Later Scripture will refer back to this principle. Acts 17:26 declares that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men… and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation.” The theological seed of that New Testament statement lies in Genesis 10.

Fourth, it provides the backdrop for the Abrahamic narrative. By listing the nations first, Scripture shows that the call of Abraham in Genesis 12 is not an isolated tribal event but part of God’s redemptive plan for the entire world. The nations scattered in Genesis 10 are the same nations later promised blessing through Abraham’s seed.

The Descendants of Japheth

Genesis 10 begins with Japheth, traditionally associated with peoples who migrated north and west of the ancient Near East.

The sons of Japheth are listed as Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras. Many historical interpretations associate these names with regions in Asia Minor, Europe, and the northern territories beyond the Black Sea.

Gomer is often linked to the Cimmerians, an ancient people of Anatolia and Eastern Europe. Magog is mentioned later in Ezekiel 38–39, associated with northern powers hostile to Israel. Madai is commonly identified with the Medes. Javan is generally associated with the Ionians or Greeks. Tubal and Meshech appear in Assyrian records and are frequently connected with peoples in Anatolia. Tiras has sometimes been associated with Thracians.

From Javan come Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim—names that scholars connect to Mediterranean island and coastal peoples. Tarshish, in particular, becomes prominent in later biblical narratives, especially in the book of Jonah.

The repeated phrase “by these were the isles of the Gentiles divided in their lands” suggests maritime expansion. Japheth’s descendants appear to represent early seafaring civilizations and Indo-European peoples spreading westward.

Theologically, Japheth’s line is often associated with the enlargement prophecy found in Genesis 9:27: “God shall enlarge Japheth.” Some interpreters view the geographic spread of Indo-European peoples across Europe and Asia as a fulfillment of this blessing. Others see it spiritually fulfilled in the inclusion of Gentiles in the blessings of the gospel.

The Descendants of Ham

The next major section lists the sons of Ham: Cush, Mizraim, Phut, and Canaan. This lineage is often associated with regions south of Israel—Africa, Egypt, and parts of the Near East.

Cush is typically connected with Ethiopia or Nubia. Mizraim is the Hebrew name for Egypt. Phut is often identified with Libya or North Africa. Canaan is the ancestor of the Canaanite peoples who later inhabit the Promised Land.

From Cush comes Nimrod, a figure of particular theological interest. Genesis describes Nimrod as “a mighty one in the earth” and “a mighty hunter before the LORD.” He is said to have begun his kingdom at Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh in the land of Shinar. Nimrod represents the rise of organized rebellion and centralized power. Many interpreters see him as the founder of early Mesopotamian civilization and as a prototype of later tyrannical rulers.

The mention of Babel in this genealogy connects directly to Genesis 11. Nimrod’s kingdom in Shinar becomes the setting for the Tower of Babel. Thus, Genesis 10 not only maps peoples but introduces the ideological conflict between human ambition and divine authority.

The descendants of Mizraim include groups often identified with ancient Egyptian and Philistine territories. The Philistines, significant adversaries of Israel, are traced back through this line.

Canaan’s descendants include the Sidonians, Hittites, Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, Hivites, Arkites, and others. These names correspond to peoples inhabiting the land later promised to Abraham. Genesis 10 therefore explains why Canaan becomes the focus of later conquest narratives.

Theologically, Ham’s lineage is often discussed in connection with the curse pronounced in Genesis 9:25 upon Canaan. Importantly, the curse is directed specifically at Canaan, not all of Ham’s descendants. Historically, misinterpretations of this passage were used to justify racial prejudice and slavery. Careful theological reading, however, notes that the text confines the curse to Canaanite peoples and situates it within redemptive history rather than racial hierarchy.

The Descendants of Shem

Genesis 10 concludes with Shem, whose name means “name” or “renown.” From Shem will eventually come Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and ultimately the Messiah.

Shem’s sons are Elam, Asshur, Arphaxad, Lud, and Aram. Elam is associated with Persia. Asshur is linked to Assyria. Arphaxad is significant because through him comes Eber, from whom the term “Hebrew” may derive. Lud is sometimes associated with Lydia in Asia Minor. Aram is connected with the Arameans or Syrians.

From Aram descend Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash. Uz is notably the homeland of Job. From Arphaxad comes Salah, and from Salah comes Eber. Eber’s sons are Peleg and Joktan. The text notes that “in his days was the earth divided,” referring either to the division of languages at Babel or possibly to geographic changes.

Joktan’s descendants are associated with Arabian tribes. The line through Peleg eventually leads to Abraham in Genesis 11.

Shem’s genealogy is presented last, likely because it is the line of promise. The narrative focus of Genesis will narrow to this lineage. The Table of Nations, therefore, ends by preparing the reader for the covenantal story that follows.

Theological Interpretations

Theologically, Genesis 10 affirms several key doctrines.

Human Unity. All nations descend from one family. This stands in contrast to polygenetic theories that propose multiple origins for humanity. Scripture presents a single origin, reinforcing both equality and accountability.

Divine Sovereignty Over Nations. God oversees the establishment and boundaries of nations. Political power, migration, and cultural development unfold under divine oversight.

Judgment and Mercy. The nations listed include future enemies of Israel, yet they also represent the world God intends to bless. Genesis 12:3 promises that “in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed.” The Table of Nations sets the stage for that promise.

Preparation for Redemption. The narrowing of focus from all nations to Shem’s line shows that God’s redemptive plan works through particular covenants while maintaining universal intent.

Historical and Scholarly Perspectives

Historically, many scholars see Genesis 10 as an ethnographic map of the ancient Near East as understood by Israel. The names often correspond to known peoples from archaeological and extra-biblical sources. Assyrian inscriptions, Egyptian records, and classical writings mention several of these groups.

Some modern scholars view the chapter as a theological document rather than a strict historical record. They argue that it reflects Israel’s understanding of neighboring nations during the first millennium BCE. Others maintain that it preserves genuinely ancient traditions rooted in early post-Flood history.

Debate continues regarding the chronological relationship between Genesis 10 and 11. Some argue Genesis 10 is topical, not strictly sequential, and therefore summarizes the dispersion before explaining it in detail.

In conservative circles, Genesis 10 is often treated as literal history. The genealogies are viewed as actual ancestral records tracing real historical migrations. This approach sees the Table of Nations as foundational to biblical anthropology.

Likely Emphases from a KJV-Only Literal Perspective

A Bible teacher who strongly emphasizes the King James Version and literal interpretation would likely stress several themes.

First, the genealogies are historical fact. The names represent real individuals who fathered real nations. The authority of the KJV text would be upheld as preserved and reliable.

Second, the unity of humanity would be strongly affirmed. Modern evolutionary anthropology and theories of racial division might be critiqued in favor of a biblical model of descent from Noah.

Third, Nimrod would likely be emphasized as the beginning of organized rebellion against God, possibly connected typologically to later world empires or even prophetic speculation regarding end-times figures.

Fourth, the dispersion at Babel would be presented as a supernatural intervention by God, not merely a sociological development.

Fifth, the seventy nations might be highlighted symbolically, emphasizing completeness and the universality of God’s plan.

Sixth, attention would likely be drawn to how later biblical prophecy references nations named in Genesis 10, showing continuity throughout Scripture.

Such teaching would underscore the reliability of Scripture from Genesis to Revelation and argue that the Table of Nations demonstrates divine inspiration through its historical accuracy and prophetic foreshadowing.

Conclusion

Genesis 10:1–32 is far more than a genealogical appendix. It provides the biblical framework for understanding the origin of nations, the unity of mankind, and the sovereignty of God over history. It explains how humanity spread across the earth after the Flood and establishes the backdrop for both judgment at Babel and redemption through Abraham.

The chapter affirms that diversity in language and geography does not negate common ancestry. It shows that God governs history even when humanity seeks autonomy. It prepares the reader for the covenant promises that will shape the rest of Scripture.

The Table of Nations stands as a theological map—one that traces the branching of humanity from one righteous family into a world of tribes and kingdoms. Whether read through historical-critical lenses or through a literalist framework that emphasizes the authority of the King James Bible, Genesis 10 remains foundational. It tells the story of how the world began again after judgment, and how from that restart would come both rebellion and redemption.

In the structure of Genesis, this chapter is a hinge. Behind it lies the Flood; ahead lies Babel and Abraham. Between judgment and promise stands the Table of Nations—a testimony that God’s purposes for humanity unfold through real families, real lands, and real history.