In many contemporary church environments, influence is often measured in scale. Attendance figures are circulated as evidence of vitality. Digital reach is tracked with precision. Leadership conferences feature strategies for expansion, branding, and visibility. Against that backdrop, the apostolic correspondence attributed to Paul presents a markedly different picture of what ministry is meant to accomplish. The focus is not institutional enlargement but personal formation. The stated aim is “for the edifying of the body of Christ,” a phrase drawn from Epistle to the Ephesians 4:12 in the King James Version. The language directs attention toward construction, but the structure in view is not an organization. It is a community of people being shaped into maturity.

Paul’s letters were written in the first century to small assemblies scattered across urban centers of the Roman world. They met in homes rather than dedicated religious complexes. They possessed no centralized bureaucracy and no access to modern communication channels. Yet in those letters Paul articulates a coherent theology of ministry that continues to challenge assumptions about success, leadership, and growth.

In his second letter to Corinth, he makes a statement that would unsettle many modern approaches: “For we preach not ourselves, but Christ Jesus the Lord.” That line, recorded in Second Epistle to the Corinthians 4:5, rejects self-promotion as a ministerial strategy. The message is not the personality of the preacher but the person of Christ. In a cultural moment that prizes platform-building, the Pauline framework shifts the center of gravity.

The emphasis on edification appears repeatedly. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 3:9, believers are described as “God’s husbandry” and “God’s building.” The imagery is communal and developmental. Leaders are co-laborers, not proprietors. Ownership rests with God. This perspective reduces the temptation to treat congregants as assets contributing to an expanding enterprise. They are, instead, the very work under construction.

The distinction is subtle but significant. When institutions become the primary object of attention, people can become means to an end. Volunteers are valued for productivity; donors for financial contribution; attendees for numerical strength. Within Paul’s letters, however, the project is reversed. The people themselves constitute the project. Programs and structures exist to support their growth in Christ, not to elevate the organization’s profile.

The Letter to the Colossians reinforces this orientation. In Epistle to the Colossians 1:28, Paul describes his labor as presenting “every man perfect in Christ Jesus.” The objective is maturity. The term translated “perfect” carries the sense of completeness or full development. It is not merely initial conversion that concerns him, but ongoing formation. Evangelistic multiplication is not minimized, yet it is not the final metric. Depth takes precedence over breadth.

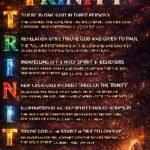

This priority challenges the modern inclination to equate growth with expansion. Congregations can increase in number while remaining shallow in doctrine. Paul’s letters display a sustained concern for theological clarity. In the Epistle to the Romans 12:2 he urges believers to be transformed by the renewing of the mind. Renewal presupposes instruction. It implies time, patience, and repetition. It cannot be manufactured through spectacle.

The same pattern appears in the Letter to Titus, where sound doctrine is presented as foundational to healthy living. Instruction is not peripheral but central. The implication is that durable communities arise from shared understanding of the gospel rather than from emotional momentum. A gathering energized by charisma may be large, but without doctrinal substance it remains fragile.

Paul’s warnings to Timothy illustrate the danger of substituting popularity for truth. In Second Epistle to Timothy 4:2–4, he anticipates a time when listeners will prefer messages that affirm rather than challenge. The temptation for leaders is to accommodate those preferences to retain attendance. Paul’s directive is different: preach the word, whether convenient or not. Faithfulness to content outweighs audience reaction.

This commitment to truth over approval appears in the apostle’s own ministry. His letters reference imprisonment, opposition, and desertion. None of these experiences align with conventional markers of success. Yet he measures his work by adherence to the gospel and by the spiritual stability of those he taught. In the First Epistle to the Thessalonians 2:19–20, he identifies the believers themselves as his “hope” and “joy.” They are not stepping stones to a larger influence; they are the evidence of faithful labor.

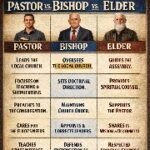

Another component of Paul’s model involves the transmission of teaching beyond his own presence. In Second Epistle to Timothy 2:2, he instructs Timothy to entrust what he has learned to reliable individuals who can teach others also. The pattern is generational. Authority is shared rather than centralized. Dependency on a single personality is discouraged. Leaders are to equip others for service, not cultivate perpetual reliance.

This distributed approach limits the formation of personality-driven movements. When disciples are trained to handle doctrine themselves, the community’s stability does not hinge on one figure. The emphasis shifts from attracting followers to cultivating teachers. Ministry becomes participatory rather than hierarchical.

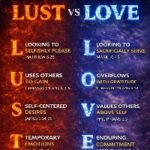

Humility further characterizes the Pauline posture. In Epistle to the Philippians 2:5–7, Paul urges believers to adopt the mindset of Christ, who “made himself of no reputation.” The call extends to leaders as well as congregants. Self-emptying contrasts sharply with self-branding. Recognition is not pursued as an end. Instead, glory is redirected toward God, echoing Paul’s statement in the First Epistle to the Corinthians 1:31 that those who boast should boast in the Lord.

The letters also place limits on the confidence placed in technique. In Second Epistle to the Corinthians 3:6, Paul contrasts the letter with the Spirit, asserting that the Spirit gives life. Systems and strategies may organize activity, but transformation is attributed to divine agency. This does not negate planning or diligence, yet it resists the notion that methodology alone can produce spiritual maturity.

A related emphasis appears in his acknowledgment of weakness. Later in the same epistle, he recounts a divine assurance that power is perfected in weakness. The implication is that visible strength and polished presentation are not prerequisites for effective ministry. God’s sufficiency compensates for human limitation. This principle undermines celebrity culture within religious contexts.

The long-term perspective in Paul’s theology further distances it from empire-building. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 3:11–15, he describes a coming evaluation of each person’s work. The imagery centers on endurance rather than size. Materials are tested by fire. Only what aligns with Christ as foundation remains. Applause and recognition are absent from the criteria.

This orientation toward future accountability recalibrates ambition. Leaders who internalize it may evaluate decisions differently. Investments in patient teaching, pastoral care, and doctrinal clarity might appear less dramatic in the short term, yet they align with the anticipated assessment. Temporary prominence offers no guarantee of lasting value.

Paul’s farewell address to the elders of Ephesus, recorded in Acts of the Apostles 20:28, reinforces pastoral responsibility. He urges them to take heed to themselves and to the flock over which the Holy Spirit has made them overseers. The imagery is protective and nurturing. The flock does not exist to elevate the shepherd’s reputation. Rather, the shepherd serves for the flock’s welfare.

Such texts collectively outline a model in which ministry is relational and instructional. It is oriented toward shaping conscience and character. Public gatherings and organizational structures serve that purpose but do not replace it. When metrics become detached from maturity, distortion follows.

The modern environment introduces pressures unknown to the first century. Social media accelerates exposure. Conferences create networks of influence. Publishing platforms enable rapid dissemination of ideas. These tools can assist edification, yet they can also tempt leaders to equate visibility with effectiveness. The Pauline letters do not anticipate digital metrics, but their principles remain applicable. The question is not how widely a message spreads, but whether it forms Christlike character in those who receive it.

Paul’s own biography illustrates this tension. He founded communities in cities such as Corinth and Philippi, yet he frequently departed after brief stays. His confidence rested not in perpetual personal oversight but in the implanted gospel and the Spirit’s ongoing work. His letters address problems candidly, revealing that growth is uneven and sometimes messy. Nevertheless, he persists in instruction rather than abandoning communities for more promising prospects.

Financial considerations also surface in his correspondence. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 9, he defends the right of ministers to receive support while simultaneously choosing at times to forego it to avoid misunderstanding. The decision reflects sensitivity to motive. Compensation is permissible, but exploitation is rejected. The welfare of believers takes precedence over personal gain.

The cumulative portrait is not anti-organization but anti-exploitation. Structures may facilitate coordination, yet they are not ends in themselves. The central aim remains the strengthening of believers’ faith and understanding. Paul’s repeated prayers for the churches focus on knowledge, love, and endurance rather than on expansion.

In Epistle to the Ephesians 4, the goal of equipping leaders is described as producing unity and stability so that believers are no longer children tossed by every wind of doctrine. The image suggests resilience. Mature individuals are less susceptible to manipulation. Ironically, an empire mindset may prefer dependence, as it preserves control. Paul’s approach seeks the opposite: informed believers capable of discernment.

This emphasis on doctrinal grounding counters the drift toward entertainment-driven gatherings. Emotional experience can be intense without producing comprehension. Paul’s insistence on intelligibility in worship, articulated in First Epistle to the Corinthians 14, underscores the value of understanding. Words that instruct outweigh displays that impress.

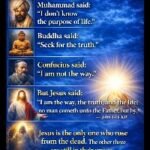

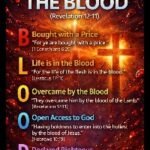

At the heart of his ministry is the proclamation of Christ’s death and resurrection. In First Epistle to the Corinthians 15:1–4, he summarizes the gospel he preached as the message that Christ died for sins, was buried, and rose again. Everything else builds upon that foundation. When leaders center their identity on this message rather than on personal distinctives, they redirect attention appropriately.

The cumulative effect of these themes is a redefinition of success. Faithfulness replaces fame. Maturity outweighs magnitude. Shared growth supersedes individual prominence. The apostolic witness does not deny the possibility of large gatherings, but it refuses to treat size as the primary indicator of divine approval.

For contemporary leaders and congregants alike, the Pauline framework invites examination of motive. Are initiatives designed to cultivate informed, stable believers? Or do they primarily enhance institutional reputation? The distinction may not always be visible externally, but over time it shapes community culture.

Believers themselves bear responsibility. An appetite for novelty or personality can encourage the very tendencies Paul cautions against. When congregations value substance, leaders are freed to prioritize teaching over theatrics. The relationship between shepherd and flock becomes reciprocal.

The endurance of Paul’s letters across centuries suggests that his model possesses durable relevance. Written without modern infrastructure, they continue to instruct communities worldwide. Their persistence may itself testify to the principle they espouse: people shaped by truth outlast structures built on spectacle.

Ultimately, the Pauline vision of ministry is inseparable from his theology of grace. If salvation is unearned, then leadership cannot claim ultimate credit for transformation. God gives the increase. Human labor participates but does not dominate. This perspective tempers ambition and fosters humility.

Institutions inevitably change, merge, or dissolve. Buildings age. Platforms evolve. Yet individuals instructed in the gospel carry that formation into families, workplaces, and subsequent generations. The investment multiplies in ways that defy immediate measurement.

The apostle’s closing remarks in several letters reflect satisfaction not with institutional achievement but with the steadfastness of believers. His joy is relational. He speaks of laboring “until Christ be formed” in them, a phrase from Epistle to the Galatians 4:19 that captures his enduring concern. Formation, not fame, defines fulfillment.

In evaluating contemporary ministry through this lens, the question becomes less about visibility and more about vitality. Are communities grounded in sound doctrine? Are individuals growing in discernment and love? Are leaders equipping others to teach and serve? These inquiries align more closely with the apostolic criteria than attendance graphs or online metrics.

The Pauline letters do not provide a blueprint for organizational charts, but they articulate a theology that resists turning people into instruments of expansion. Instead, they present ministry as participation in God’s work of shaping believers into the likeness of Christ. In that vision, influence is measured not by the height of an institution but by the depth of transformed lives.