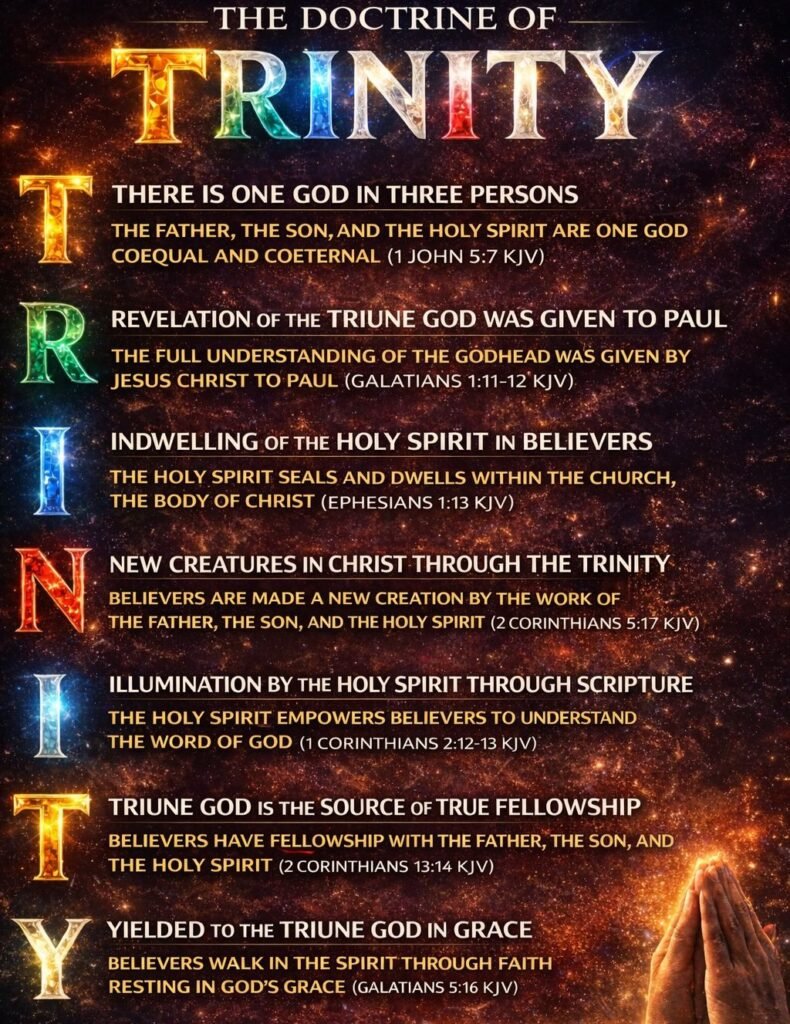

In many congregations the doctrine of the Trinity is treated as settled vocabulary—recited in creeds, embedded in hymns, and assumed in liturgy. Yet when pressed for definition, even long-time churchgoers often struggle to articulate what Christians mean when they speak of one God in three Persons. For some, the term feels abstract, the product of later theological debate rather than scriptural clarity. For others, it is a mystery accepted but rarely examined.

The apostle Paul did not use the word “Trinity,” yet his letters are saturated with a tri-personal understanding of God. His closing benediction to the Corinthians provides a concise example: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Ghost, be with you all” (2 Corinthians 13:14, KJV). In a single sentence, Paul names the Lord Jesus Christ, God the Father, and the Holy Spirit, assigning to each a distinct role in the believer’s experience while assuming unity of divine action.

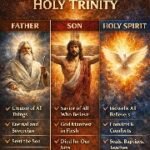

The claim that the Trinity is biblical revelation rather than ecclesiastical invention rests largely on passages such as this. In Pauline theology, the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are neither interchangeable titles nor separate deities operating independently. They are personally distinct yet inseparably one in essence and purpose. To grasp this structure is not to indulge speculative theology; it is to understand how Paul frames salvation, security, and daily Christian living.

Paul was a monotheistic Jew. His affirmation in 1 Corinthians 8:6 reflects continuity with Israel’s confession in Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord” (KJV). Writing to believers in a polytheistic environment, Paul declares, “But to us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we in him; and one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things, and we by him” (KJV). The structure is significant. He distinguishes between “one God” and “one Lord Jesus Christ” while maintaining a unified creative and sustaining role. Both are implicated in the origin and ongoing existence of “all things.”

This pairing does not fragment monotheism. Rather, it expands the understanding of divine identity in light of Christ’s revelation. In Philippians 2:6, Paul writes of Christ Jesus “who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God” (KJV). Equality with God is not portrayed as a usurpation but as intrinsic to Christ’s identity. At the same time, Paul maintains distinction. Christ humbles Himself, takes on human likeness, and obeys unto death. The Son relates to the Father without ceasing to share divine status.

The Spirit, likewise, is not presented as an impersonal force. In Romans 8, Paul describes the Spirit as indwelling believers, interceding for them, and bearing witness with their spirit that they are children of God (Romans 8:16, 26, KJV). Personal attributes—knowledge, will, communication—are ascribed to Him. Yet Paul does not treat the Spirit as a separate deity. The Spirit is called “the Spirit of God” and “the Spirit of Christ” within the same chapter, underscoring unity of operation.

The coherence of Paul’s theology rests on the assumption that the Godhead is singular in essence and plural in personal distinction. This is not a philosophical construction imported into the text but an interpretive synthesis drawn from repeated patterns in his letters. When Paul speaks of salvation, he consistently distributes roles across Father, Son, and Spirit without implying division of deity.

Ephesians 1 provides a sustained example. Paul begins by blessing “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Ephesians 1:3, KJV), who has chosen believers in Christ before the foundation of the world (Ephesians 1:4). The Father is portrayed as the architect of redemption. The Son is described as the one “in whom we have redemption through his blood” (Ephesians 1:7, KJV). The Spirit appears as the seal and earnest of the believer’s inheritance (Ephesians 1:13–14). The sequence is purposeful but unified. The Father plans, the Son accomplishes, the Spirit applies.

The distinction does not suggest hierarchy of essence. Paul never implies that the Son or Spirit are lesser beings. In Colossians 2:9, he writes concerning Christ, “For in him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily” (KJV). The term “Godhead” signifies the totality of divine nature. The fullness is not partial or delegated; it is complete. At the same time, Paul prays to the Father through the Son in the Spirit, reflecting relational order within the unity.

The question of how Paul received this understanding bears examination. In Galatians 1:11–12, he insists that the gospel he preached was “not after man,” neither received from human teachers but “by the revelation of Jesus Christ” (KJV). In Ephesians 3:3–5, he speaks of a “mystery” made known to him by revelation, which in other ages was not made known as it is now revealed. This mystery concerns the formation of a joint body of Jewish and Gentile believers in Christ. Within this revelation, the tri-personal nature of God’s saving work becomes explicit.

Romans 16:25 refers to “my gospel, and the preaching of Jesus Christ, according to the revelation of the mystery” (KJV). Paul sees his apostolic commission as clarifying aspects of God’s redemptive plan previously hidden. That clarification includes the relationship between the risen Christ and the indwelling Spirit. The Spirit is sent in Christ’s name and mediates Christ’s life to believers. Yet the Spirit is also called the Spirit of God, emphasizing that the work of redemption is not divided among competing agents but executed in coordinated unity.

Salvation in Paul’s letters is therefore irreducibly Trinitarian. In 2 Thessalonians 2:13–14, he writes that “God hath from the beginning chosen you to salvation through sanctification of the Spirit and belief of the truth: Whereunto he called you by our gospel” (KJV). The Father’s choosing, the Spirit’s sanctifying activity, and the proclamation concerning the Son operate together. In Titus 3:5–6, Paul explains that believers are saved “by the washing of regeneration, and renewing of the Holy Ghost; Which he shed on us abundantly through Jesus Christ our Saviour” (KJV). The Father’s mercy, the Son’s mediating role, and the Spirit’s renewing work are inseparable components of a single saving act.

Understanding this structure safeguards the doctrine of grace. If salvation were the initiative of one Person and the reluctant concession of another, grace would be fractured. Instead, Paul presents redemption as the unified expression of divine love. Romans 5:8 states, “But God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (KJV). The love originates with God the Father and is enacted through the Son. The Spirit, as described in Romans 5:5, sheds that love abroad in believers’ hearts.

Security likewise rests on Trinitarian coherence. In Romans 8, Paul unfolds a sequence: those foreknown are predestinated, called, justified, and glorified (Romans 8:29–30, KJV). The Father’s purpose is executed through the Son’s atoning work and confirmed by the Spirit’s indwelling witness. The result is a crescendo of assurance: nothing “shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:39, KJV). The unity of divine action underwrites the permanence of salvation.

The Spirit’s indwelling presence is particularly emphasized in Paul’s correspondence. In 1 Corinthians 6:19, he asks, “Know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost which is in you, which ye have of God?” (KJV). The believer becomes the dwelling place of God through the Spirit. Yet Paul does not detach this indwelling from Christ. In Galatians 2:20, he declares, “Christ liveth in me” (KJV). The indwelling Spirit mediates the life of the risen Christ, demonstrating relational distinction without ontological separation.

Illumination of truth is also attributed to the Spirit within the context of the Godhead’s unified purpose. In 1 Corinthians 2:12–13, Paul writes, “Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the spirit which is of God; that we might know the things that are freely given to us of God” (KJV). The Spirit reveals what the Father has given through the Son. The natural person cannot receive these things because they are spiritually discerned (1 Corinthians 2:14, KJV). The capacity to understand divine revelation is itself a Trinitarian gift.

Paul’s exhortations concerning Christian conduct assume this framework. “Walk in the Spirit,” he commands in Galatians 5:16 (KJV). The ability to walk in a manner pleasing to God arises from the Spirit’s enabling presence, grounded in the Son’s redemptive accomplishment and the Father’s gracious purpose. The fruit that results—love, joy, peace, longsuffering—reflects the character of God Himself (Galatians 5:22–23, KJV). Ethical transformation is not human self-improvement but participation in divine life.

The doctrine of the Trinity, then, is not an isolated abstraction but the organizing principle of Paul’s theology. Remove the Father’s electing love, and grace loses its origin. Remove the Son’s incarnate obedience and atoning death, and grace loses its historical accomplishment. Remove the Spirit’s indwelling presence, and grace loses its experiential application. The coherence of salvation depends on the unity and distinction within the Godhead.

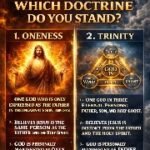

Misunderstandings of the Trinity often arise from attempts either to divide or to collapse the Persons. To divide them is to drift toward tritheism, imagining three independent gods cooperating loosely. To collapse them is to deny personal distinction, reducing Father, Son, and Spirit to modes of a single actor. Paul avoids both errors by consistently naming the three together while maintaining relational language. The Father sends the Son; the Son redeems; the Spirit seals. Yet all are identified with the one divine name.

The communal dimension of Christian life further reflects this tri-personal structure. In 1 Corinthians 1:9, Paul speaks of believers being called “unto the fellowship of his Son Jesus Christ our Lord” (KJV). Fellowship is also described as participation in the Spirit (Philippians 2:1, KJV). Prayer is addressed to the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit (Ephesians 2:18). The rhythm of Christian devotion mirrors the relational life of the Godhead.

Paul’s doxologies frequently return to this theme. In Romans 11:36, he concludes a dense theological exposition with, “For of him, and through him, and to him, are all things: to whom be glory for ever” (KJV). While the immediate referent is God, the context of chapters 8–11 has already intertwined Father, Son, and Spirit in the unfolding of redemption. Glory is attributed to the one God whose saving purpose encompasses all three Persons.

For Paul, to misunderstand the Trinity would be to misunderstand the gospel. If Christ were less than fully divine, His atoning death could not reconcile humanity to God. If the Spirit were not truly God, His indwelling presence could not secure eternal life. If the Father were not personally distinct, the language of sending, loving, and adopting would collapse into abstraction. The tri-personal nature of God is not an optional theological addendum; it is the architecture of grace.

In contemporary discussions, the Trinity is sometimes dismissed as a paradox beyond comprehension. Paul does not deny mystery, but he insists on revelation. The mystery once hidden is now made manifest through apostolic proclamation. Believers are not called to solve a philosophical puzzle but to receive what has been disclosed. The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Ghost are not theoretical categories; they are lived realities grounded in divine unity.

The continuing relevance of this doctrine becomes evident wherever the gospel is proclaimed. When forgiveness is announced in Christ’s name, it presupposes the Father’s authority and the Spirit’s application. When believers gather in worship, they address the Father, exalt the Son, and depend upon the Spirit. The pattern is embedded in Christian identity.

Ultimately, Paul’s theology directs attention away from speculative curiosity and toward grateful acknowledgment. The triune God is not presented as an object of detached analysis but as the source of salvation and the sustainer of hope. The unity of essence and distinction of Persons ensure that grace is neither accidental nor fragmented. It flows from the eternal counsel of God, accomplished in the historical work of Christ, and realized in the present ministry of the Spirit.

In this light, the doctrine of the Trinity stands not as theological trivia but as the framework within which the Christian life unfolds. One God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—acts in harmony to redeem, indwell, instruct, and preserve. The believer’s assurance, transformation, and future inheritance are inseparable from this tri-personal reality. For Paul, to know God in grace is to encounter Him as Father, through the Son, by the Spirit.