In contemporary culture, the word “love” is invoked to justify nearly every kind of desire. Advertising campaigns, entertainment media, and even moral debates appeal to it as the highest good. At the same time, the word “lust” is often reduced to a narrow category of sexual misconduct, detached from broader questions of character and spiritual formation. The two concepts are frequently conflated because both involve longing, attraction, and pursuit. Yet within the framework of Pauline theology, they represent fundamentally different orientations of the human heart. One arises from what the apostle Paul calls “the flesh.” The other is the fruit of the Spirit of God.

The distinction is not merely semantic. It reaches into the daily life of the believer, shaping motives, relationships, ambitions, and habits. In his letter to the Galatians, Paul writes, “Walk in the Spirit, and ye shall not fulfil the lust of the flesh” (Galatians 5:16, KJV). The instruction is addressed not to unbelievers seeking justification, but to Christians already placed into Christ by grace. The issue is not how to be saved, but how to live. Paul’s concern is sanctification—how redeemed people conduct themselves in a world still marked by corruption.

To understand the tension between lust and love in Pauline doctrine, one must begin with his anthropology. Paul’s letters consistently present humanity as divided in experience, even after conversion. In Romans 7, he describes the internal conflict between the desire to do good and the persistent presence of sin in the members of the body. “For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh,) dwelleth no good thing” (Romans 7:18, KJV). The flesh, in Paul’s usage, does not refer merely to the physical body but to the fallen human nature inherited from Adam. It is the source of impulses that resist God’s will.

By contrast, love—often translated from the Greek term agape and rendered as “charity” in the King James Version—has a different origin. In Romans 5:5, Paul states that “the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us.” Love, in this sense, is not self-generated sentiment. It is produced by the indwelling Spirit. It is not the improvement of the flesh but the expression of a new life granted by grace.

This distinction is central to Paul’s argument in Galatians 5. “For the flesh lusteth against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh: and these are contrary the one to the other” (Galatians 5:17, KJV). The conflict is ongoing. The believer does not lose the old nature at conversion; rather, he or she gains a new one. Christian maturity, then, is not the eradication of desire but its redirection. It is the daily decision to yield to the Spirit rather than to indulge the flesh.

In popular discourse, lust is often framed primarily as sexual craving. Paul’s treatment is broader. In Galatians 5:19–21, he lists “the works of the flesh,” which include not only adultery and fornication but also hatred, variance, emulations, wrath, strife, envyings, and drunkenness. Lust is not confined to physical appetite; it encompasses any self-centered desire that operates independently of God’s will. It is the inward drive to gratify oneself, regardless of consequence.

Love, by contrast, appears first in Paul’s description of “the fruit of the Spirit” (Galatians 5:22). It heads the list, followed by joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, and temperance. The singular word “fruit” suggests a unified product of the Spirit’s work, not a menu of optional virtues. Love is the controlling disposition that shapes the rest.

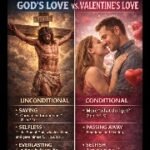

The divergence between lust and love becomes particularly visible in the way they regard other people. Lust approaches others as instruments for personal satisfaction. It asks, implicitly or explicitly, “How can this person meet my needs?” Whether in romantic relationships, friendships, or professional settings, lust reduces individuals to objects. James, though not writing within the same Pauline framework, captures the dynamic succinctly: “Every man is tempted, when he is drawn away of his own lust, and enticed” (James 1:14, KJV). The movement begins inwardly and moves outward, often disregarding the well-being of others.

Paul’s understanding of love stands in sharp contrast. In Philippians 2:4, he urges believers to “look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others.” The model he presents is Christ Himself, who “made himself of no reputation” and took “the form of a servant” (Philippians 2:7, KJV). Love, in Pauline thought, is inseparable from self-giving. It does not deny desire altogether but subordinates it to the good of another.

This is perhaps most fully articulated in 1 Corinthians 13. Writing to a church plagued by rivalry and self-assertion, Paul describes charity as patient and kind. It “seeketh not her own” and “is not easily provoked” (1 Corinthians 13:5, KJV). The chapter is often read at weddings, but its context is corrective. The Corinthians were exercising spiritual gifts for personal recognition rather than for edification. Paul’s response is not to abolish gifts but to insist that their exercise be governed by love.

The difference between lust and love also emerges in their respective outcomes. Lust promises immediate gratification but yields instability. Proverbs 14:12, though part of Israel’s wisdom literature rather than Pauline epistle, expresses a principle Paul would affirm: “There is a way which seemeth right unto a man, but the end thereof are the ways of death” (KJV). In Romans 8:6, Paul writes, “For to be carnally minded is death; but to be spiritually minded is life and peace.” The mind set on the flesh produces alienation and unrest.

Love, on the other hand, has enduring value. “Charity never faileth” (1 Corinthians 13:8, KJV). It persists beyond the temporary conditions of this age. For Paul, the life shaped by love is not only morally superior but eschatologically significant. In 2 Corinthians 5:10, he reminds believers that “we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ.” The issue at that tribunal is not condemnation for sin—Christ has borne that—but evaluation of works. Actions motivated by the flesh will not endure; those rooted in love will.

Paul’s insistence that believers are “not under the law, but under grace” (Romans 6:14, KJV) further clarifies the matter. The contrast between lust and love is not resolved by external regulation alone. Law can restrain behavior, but it cannot transform desire. In Galatians, Paul argues that returning to legalism does not produce holiness; it fosters either pride or frustration. The Spirit’s work, not the imposition of rules, generates genuine love.

This emphasis on grace distinguishes Pauline teaching from systems that equate morality with compliance. For Paul, the believer’s identity is decisive. In Ephesians 1, he describes Christians as “blessed with all spiritual blessings in heavenly places in Christ” (Ephesians 1:3, KJV). In Colossians 3:3, he states, “For ye are dead, and your life is hid with Christ in God.” The exhortations that follow—putting off anger, malice, and impurity—are grounded in this new position. One walks in love not to become accepted but because one is already accepted in the Beloved.

This does not render the struggle imaginary. Paul acknowledges the reality of temptation. In Romans 13:14, he instructs believers to “make not provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof.” The language suggests intentionality. While the flesh remains present, it need not dominate. The Spirit provides both desire and power for obedience.

In practical terms, the difference between lust and love can be observed in patterns of speech, use of time, and financial priorities. A person driven by lust may pursue relationships primarily for validation or pleasure, abandon commitments when novelty fades, or manipulate circumstances for personal advantage. A person walking in love, by contrast, exhibits consistency, patience, and a willingness to sacrifice short-term gain for long-term good.

Paul’s pastoral letters reinforce this. In 1 Thessalonians 4:3–5, he writes, “For this is the will of God, even your sanctification, that ye should abstain from fornication: That every one of you should know how to possess his vessel in sanctification and honour; Not in the lust of concupiscence.” The call is not merely to avoid scandal but to honor others. Sexual purity, in this framework, is an expression of respect rooted in love.

The social implications are significant. In a culture that prizes personal fulfillment above communal responsibility, Paul’s vision is countercultural. Love “edifieth” (1 Corinthians 8:1, KJV). It builds up the community rather than fragmenting it. Lust, by contrast, corrodes trust. It treats relationships as disposable and commitments as negotiable.

Importantly, Paul does not reduce love to emotion. Feelings may accompany it, but they are not its foundation. In Ephesians 4:15, he speaks of “speaking the truth in love.” Love is compatible with honesty and correction. It seeks the ultimate good of another, even when that involves discomfort. Lust avoids inconvenience; love endures it.

The theological foundation for this ethic lies in Christ’s self-giving. In Ephesians 5:2, Paul urges believers to “walk in love, as Christ also hath loved us, and hath given himself for us an offering and a sacrifice to God.” The cross is not only the means of justification but the pattern of conduct. Divine love is demonstrated not by indulgence but by costly obedience.

The long-term trajectory of lust and love also differs in terms of freedom. While lust presents itself as liberation—freedom from restraint—it often leads to bondage. Peter writes of those who promise liberty while being “the servants of corruption” (2 Peter 2:19, KJV). Paul echoes this dynamic in Romans 6, where he contrasts slavery to sin with servitude to righteousness. True freedom, in his account, is the ability to do what aligns with God’s design.

Love operates within this freedom. “For, brethren, ye have been called unto liberty; only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another” (Galatians 5:13, KJV). Liberty is not autonomy but empowerment to serve. It is the release from sin’s dominion so that one may act in accordance with the Spirit.

The question remains how believers cultivate such love in daily life. Paul consistently points to the renewal of the mind. In Romans 12:2, he exhorts, “Be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind.” Transformation begins with internal reorientation. As the believer saturates his or her thinking with truth, desires gradually align with God’s purposes.

This process is neither instantaneous nor automatic. It involves intentional participation—prayer, study, fellowship, and accountability. Yet the power is not self-derived. The Spirit, who indwells every believer, produces fruit over time. The contrast between lust and love, then, is not a call to moral heroism but to dependence.

In the final analysis, Paul’s teaching presents two fundamentally different ways of living. Lust is characterized by self-reference, immediacy, and instability. Love is marked by other-centeredness, endurance, and spiritual vitality. Both involve desire, but they differ in direction and destination.

At the judgment seat of Christ, motives will be revealed. Works performed for self-exaltation will not endure; those done in love will receive reward (1 Corinthians 3:14, KJV). The stakes are not merely temporal. They touch eternity.

For Paul, the answer to lust is not repression alone but redirection. “Walk in the Spirit,” he writes, “and ye shall not fulfil the lust of the flesh.” The promise is not that temptation disappears, but that obedience is possible. In a culture where desire is often enthroned, his message remains bracingly clear: the quality of one’s love reveals the source of one’s life.

The choice before believers is not between desire and detachment, but between two kinds of desire. One consumes. The other consecrates. One narrows the soul to the horizon of self. The other enlarges it toward God and neighbor. In Pauline doctrine, sanctification unfolds in that daily decision—whether to gratify the flesh or to yield to the Spirit who produces love.