Muhammad and Jesus Christ: Examining Competing Truth Claims in Light of the Pauline Gospel

In an era that prizes inclusivity and interfaith harmony, public conversations about religious difference are often softened by a familiar phrase: “All religions ultimately lead to the same God.” It is a sentiment repeated in classrooms, media interviews, and social discourse. The idea promises unity and reduces friction. Yet it collapses under scrutiny when measured against the internal claims of the religions themselves.

Islam and Christianity, the world’s two largest faith traditions, both claim continuity with Abraham. Both revere Jesus in some form. Both assert divine revelation. Yet they diverge sharply on the identity of Christ, the nature of God, and the means of salvation. These differences are not minor variations in ritual; they represent incompatible truth claims.

The Apostle Paul, writing to the church at Corinth, stated plainly: “But we preach Christ crucified…” (1 Corinthians 1:23, KJV). That declaration stands at the center of historic Christianity. It is not simply a slogan; it is the defining content of the Christian message.

This discussion is not an exercise in hostility or cultural rivalry. It is an examination of competing theological assertions. When claims involve eternal destiny, clarity matters more than sentiment.

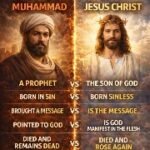

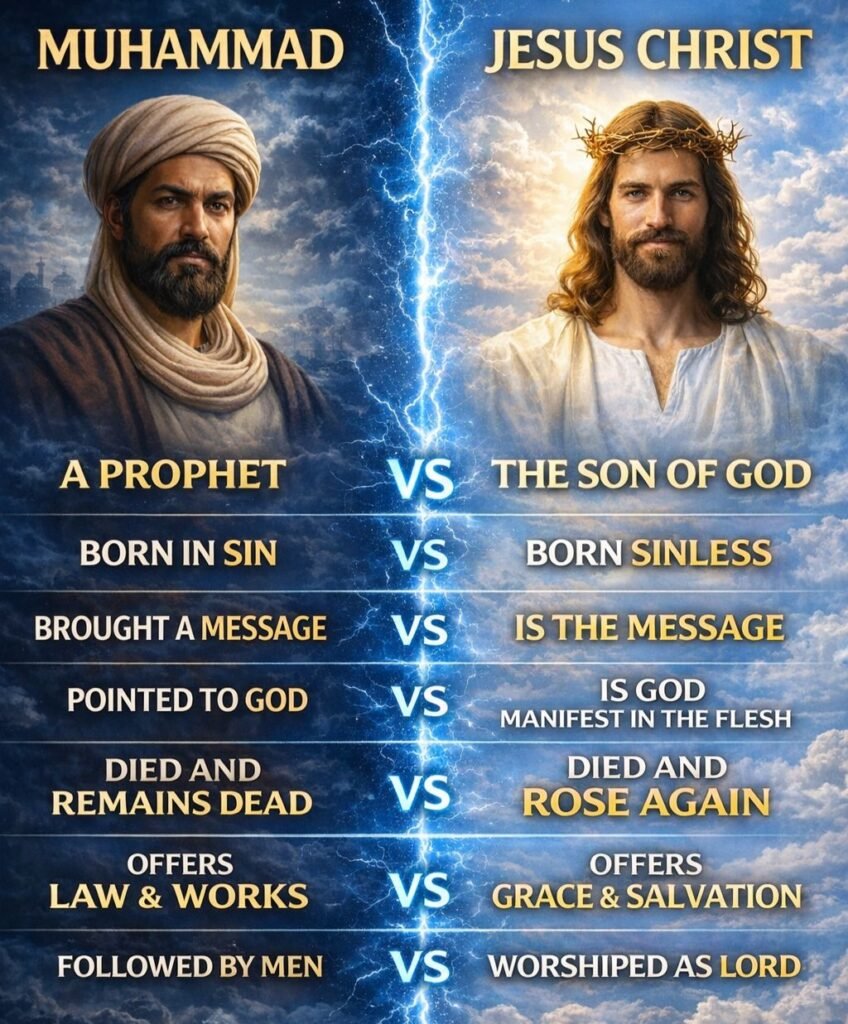

The Question of Identity

Islam affirms that Muhammad was the final prophet in a line that includes figures familiar to biblical readers—Abraham, Moses, and even Jesus. He is described as a messenger entrusted with delivering the Qur’an, which Muslims regard as the final and complete revelation of God.

Christianity, by contrast, does not present Jesus merely as a prophet among prophets. The Gospel of John opens with the statement that “the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Later, the same chapter affirms that “the Word was made flesh” (John 1:14). In Pauline theology, Jesus is not only Messiah but the visible manifestation of the invisible God (Colossians 1:15).

The difference is foundational. In Islam, Muhammad is fully human—honored but not divine. In Christianity, Jesus is described as both fully human and fully divine. Paul writes in 1 Timothy 3:16 of “God manifest in the flesh,” and in Colossians 2:9 that in Christ “dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily.”

If Jesus is God incarnate, then His authority transcends that of any prophet. If He is not, then Christian worship of Him would be idolatry. The issue is binary, not symbolic.

Human Nature and Sin

Paul’s epistle to the Romans outlines a universal diagnosis: “By one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin” (Romans 5:12). The apostle describes humanity as fallen, in need of redemption.

Islam also acknowledges human weakness but rejects the concept of inherited sin in the Pauline sense. While acknowledging moral failure, Islamic theology emphasizes individual accountability rather than a pervasive Adamic condition requiring substitutionary atonement.

In Christian doctrine, the sinlessness of Christ is indispensable. Hebrews 4:15 states that He was “in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin.” Paul reinforces this in 2 Corinthians 5:21, declaring that Christ “knew no sin” yet was made sin for us.

Muhammad, according to Islamic sources, sought forgiveness and identified himself as a servant of God. Christianity, however, insists that the Savior must be without sin to qualify as a substitute. A redeemer who shares in the same moral debt as those he seeks to rescue cannot settle their account.

This distinction shapes the entire structure of salvation within each tradition.

Revelation: A Book or a Person?

Islam centers on a book believed to be the literal word of God delivered to Muhammad. The Qur’an functions as final authority, guiding belief and practice.

Christianity, especially in Pauline thought, centers on a Person. While Scripture is authoritative, Paul’s message revolves around the proclamation of Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:1–4). Christianity’s central claim is not merely that a text was revealed, but that God acted in history through the incarnate Son.

Jesus’ own words in John 14:6—“I am the way, the truth, and the life”—present truth as embodied rather than abstract. The Christian gospel is inseparable from the identity of Christ Himself.

The contrast here is significant. One faith emphasizes submission to revealed law; the other proclaims reconciliation through a crucified and risen Lord.

The Cross and Its Meaning

Few symbols are more contested between Islam and Christianity than the Cross. Islamic teaching traditionally denies that Jesus was crucified, asserting instead that He was not killed in the manner described in the New Testament.

For Paul, however, the Cross is central. He writes in Galatians 6:14 that he boasts only “in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.” In 1 Corinthians 1:18, he describes the message of the Cross as foolishness to some but the power of God to those who believe.

Without the crucifixion, there is no atonement in Christian theology. Without the resurrection, Paul says, faith is vain (1 Corinthians 15:17). The Christian gospel hinges entirely on these historical claims.

Islam reveres Jesus as a prophet but rejects the necessity of His sacrificial death. Christianity declares that without shedding of blood there is no remission (Hebrews 9:22).

These views cannot both be true.

Resurrection as Vindication

Paul writes in Romans 1:4 that Jesus was “declared to be the Son of God with power… by the resurrection from the dead.” The empty tomb functions in Christianity as divine validation of Christ’s identity and mission.

Muhammad’s death, by contrast, marked the end of his earthly leadership. Islam does not claim his resurrection. His authority rests on revelation received during life, not on victory over death.

For Paul, the resurrection is not symbolic triumph but literal conquest. In 1 Corinthians 15, he calls Christ “the firstfruits” of those who sleep, guaranteeing future resurrection for believers.

The presence or absence of resurrection claims separates a teacher from a Savior who defeats death.

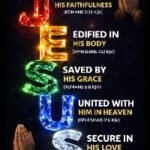

Means of Salvation

Perhaps the most consequential divergence concerns how salvation is obtained. Islamic doctrine emphasizes submission to God’s will, adherence to prescribed practices, and hope in divine mercy. Assurance of salvation is not absolute; final judgment rests with God.

Paul’s letters present salvation as a gift received through faith apart from works. “By grace are ye saved through faith… not of works” (Ephesians 2:8–9). Romans 11:6 states that if salvation is by grace, it is no longer by works.

The difference is not about moral effort but about the basis of acceptance. In Christianity, righteousness is imputed through faith in Christ’s finished work. In Islam, righteousness is pursued through obedience and weighed at judgment.

The theological frameworks are incompatible. One rests on completed atonement; the other on hopeful compliance.

Worship and Allegiance

Islam is unambiguous in rejecting worship of Muhammad. He is honored but not deified. The strict monotheism of Islam forbids associating partners with God.

Christianity, conversely, affirms worship of Jesus. In John 20:28, Thomas addresses the risen Christ as “My Lord and my God.” Paul writes in Philippians 2:9–11 that every knee shall bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.

If Jesus is not divine, such worship is blasphemous. If He is divine, withholding worship would be denial.

The divergence here is absolute.

The Pauline Dispensation of Grace

Central to Paul’s theology is the concept of a distinct dispensation revealed to him. In Ephesians 3, he speaks of a mystery previously hidden but now disclosed—the formation of a unified Body of Christ composed of Jew and Gentile.

This dispensation emphasizes heavenly position rather than earthly theocracy. Believers are said to be seated with Christ in heavenly places (Ephesians 2:6). Their citizenship is in heaven (Philippians 3:20).

Islam, by contrast, envisions a community ordered under divine law with earthly expression. Its structure integrates worship, governance, and legal code.

Paul’s message focuses on spiritual union with Christ secured through grace. The contrast between law-centered religion and grace-centered redemption defines the theological divide.

Mediator and Access to God

Paul identifies one mediator between God and men—the man Christ Jesus (1 Timothy 2:5). Mediation implies both representation and reconciliation. Christ’s unique role rests on His dual nature and sacrificial act.

Islam acknowledges prophets as conveyors of revelation but does not present Muhammad as mediator in the Pauline sense of substitutionary atonement.

The Christian claim is exclusive not by cultural preference but by doctrinal necessity. If Christ alone bridges the gap between God and humanity through His blood, then no other figure occupies that position.

Truth Claims and Tolerance

Modern society often equates disagreement with hostility. Yet clarity about truth claims need not produce animosity. Recognizing theological incompatibility does not require personal contempt.

Paul himself expressed sorrow for those who rejected Christ (Romans 9:2–3). His missionary journeys reflect engagement rather than avoidance.

Examining Muhammad and Jesus side by side is not about ethnic rivalry or geopolitical tension. It is about evaluating competing assertions concerning God’s identity and humanity’s need.

Conclusion

The comparison between Muhammad and Jesus Christ ultimately centers on one question: Who is Jesus?

If He is merely a prophet, then Christianity’s worship of Him is misplaced. If He is God manifest in the flesh, crucified and risen, then no prophet can rival His authority.

Paul’s proclamation remains clear: “We preach Christ crucified.” That message stands distinct from any religious system built on law, submission, or moral striving.

This is not a matter of tradition inherited from geography or culture. It is a matter of truth. One worldview asserts that God sent guidance through a man. The other declares that God came Himself, bore sin, rose from the dead, and offers salvation by grace through faith.

The implications extend beyond academic debate. According to Paul, eternal life hinges on the identity and work of Christ.

“He that hath the Son hath life” (1 John 5:12).

The divergence between Islam and Christianity cannot be reconciled by appeals to shared values. Their foundational claims differ at the level of personhood, atonement, resurrection, and grace.

In the final analysis, the question is not which tradition feels familiar or culturally resonant. It is whether Jesus Christ is who He claimed to be.

For Paul, and for historic Christianity grounded in his gospel, the answer is unequivocal.