Is Tithing a Scam?

A Pauline Examination of Giving Under Grace

In churches across America and beyond, few topics generate as much quiet tension as money. The collection plate still passes, digital portals now replace envelopes, and pastors continue to preach about stewardship. Yet beneath the familiar rhythms of Sunday giving lies a deeper theological question that refuses to go away: Is mandatory tithing a biblical requirement for Christians today—or has it been misapplied?

For many believers, the issue is not generosity itself. Christians broadly agree that giving is biblical. The disagreement centers on obligation. Is the ten-percent tithe binding upon members of the Body of Christ, or does it belong exclusively to Israel under the Mosaic covenant? And if the latter is true, what are the implications when churches enforce it?

At the center of this debate stands a verse from Paul’s letter to the Galatians:

“Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage.” — Galatians 5:1 (KJV)

Paul’s warning was not about finances per se. It addressed the reintroduction of Mosaic law into a grace-based gospel. Yet for many theologians and pastors who emphasize dispensational distinctions, the principle applies directly to modern tithing mandates. If believers today are not under the Law but under Grace, as Paul writes in Romans 6:14, then any compulsory financial obligation rooted in Mosaic legislation demands scrutiny.

This article does not argue against generosity. It examines whether the tithe, as commonly taught in churches today, aligns with Pauline doctrine or contradicts it.

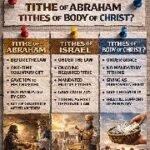

The Mosaic Framework of the Tithe

The word “tithe” simply means “a tenth.” In the Hebrew Scriptures, it carried legal weight. Leviticus 27:30 states that the tithe belonged to the Lord. Numbers 18:21 assigns it to the Levites as compensation for their service. Malachi 3:8 warns Israel against “robbing God” by withholding it.

The context is unmistakable. The tithe functioned within a national covenant between God and Israel. It was not a casual offering but a structured component of the Mosaic system. It supported a specific priesthood—the sons of Levi—who had no inheritance in the land. It was largely agricultural, consisting of crops and livestock. It was tied to the Temple economy and enforced by covenantal consequence.

Failure to comply was not merely poor stewardship; it was covenant breach. Under Deuteronomy, obedience brought blessing; disobedience brought curse.

That system, however, presupposed realities that do not exist today. There is no Levitical priesthood functioning in Jerusalem. There is no Temple collecting agricultural tribute. There is no theocratic nation under Mosaic governance.

The question is not whether the tithe existed. It did. The question is whether its legal authority extends into the present dispensation.

Israel’s Covenant Versus the Church’s Calling

The Apostle Paul draws a sharp distinction between Israel and the Body of Christ. In Romans 9:4, he lists Israel’s privileges: covenants, law, promises, and temple service. Amos 3:2 underscores Israel’s unique national relationship with God: “You only have I known of all the families of the earth.”

The Mosaic Law was not given to Gentile nations. It was delivered to Israel at Sinai. Its ordinances governed Israel’s worship, economy, and civil structure. The tithe was embedded within that framework.

Paul, however, describes a different revelation given to him—what he calls “the dispensation of the grace of God” in Ephesians 3:2. This dispensation introduced truths previously hidden, including the formation of a new body composed of Jew and Gentile on equal footing.

If the Church is not Israel, and if believers today are not under Israel’s covenant, then importing Israel’s financial regulations into the Church requires theological justification.

Some argue that the tithe predates the Law because Abraham gave a tenth to Melchizedek. Yet Paul never cites that event as a command for the Church. Instead, when addressing giving in his epistles, he outlines principles strikingly different from Mosaic requirements.

The Cross and the End of Legal Obligation

Paul’s theology of the Cross includes a radical statement in Colossians 2:14: Christ blotted out “the handwriting of ordinances that was against us,” nailing it to the cross. In Romans 10:4, he writes, “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to every one that believeth.”

These verses are not marginal. They define the believer’s relationship to the Law. Galatians 2:19 adds, “I through the law am dead to the law, that I might live unto God.”

If the Law’s authority ended at the Cross, then its ordinances—including its financial stipulations—no longer bind those in Christ. To reimpose them as mandatory is, in Paul’s words, to return to a “yoke of bondage.”

This does not eliminate moral instruction or generosity. It changes the basis from legal enforcement to grace-motivated response.

The Silence of Paul on Tithing

A notable feature of Paul’s letters is what they do not contain. Across Romans, Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians, and the pastoral epistles, there is no command to tithe.

Paul addresses money frequently. He instructs the Corinthians to set aside funds weekly “as God hath prospered him” (1 Corinthians 16:2). He commends cheerful giving in 2 Corinthians 9:7, specifying that it should not be “of necessity.” He thanks the Philippians for their financial partnership, describing it as “an odour of a sweet smell” (Philippians 4:18).

Yet nowhere does he enforce a ten-percent rule.

For proponents of grace-centered theology, this omission is not accidental. If tithing were binding upon the Church, Paul—who wrote extensively about practical Christian living—would likely have addressed it directly.

Grace Giving Defined

Paul’s most comprehensive teaching on giving appears in 2 Corinthians 8–9. There, he presents generosity as voluntary, proportionate, and motivated by joy. The Macedonians gave beyond their ability—not because they were compelled, but because they desired to participate in ministry.

The phrase “not grudgingly, or of necessity” stands in contrast to legal obligation. Under the Law, the tithe was required. Under grace, giving flows from willingness.

Paul also links giving to prosperity—not in the modern sense of wealth guarantees, but in the practical sense of capacity. “As God hath prospered him” introduces flexibility. The standard is not fixed percentage but personal ability guided by conscience.

In this framework, generosity becomes worship, not taxation.

The Use of Fear in Fundraising

Despite the absence of a Pauline command, many churches continue to teach that failure to tithe invites financial hardship. Malachi 3:8–10 is often cited: “Will a man rob God?”

The prophetic rebuke, however, was addressed to post-exilic Israel under covenant law. Applying its curses to grace believers raises serious doctrinal questions.

Paul insists in Romans 8:15 that believers have not received “the spirit of bondage again to fear.” Second Timothy 1:7 affirms that God has not given a spirit of fear. Galatians 3:10 warns that those who rely on the works of the Law are under a curse.

If believers today are not under the Law, invoking Malachi’s curse to enforce giving risks reintroducing bondage where Christ established liberty.

Fear-based fundraising may be effective, but effectiveness does not equal doctrinal accuracy.

Financial Pressure and Spiritual Confusion

When giving becomes a benchmark of spirituality, subtle distortions emerge. Those who meet percentage targets may feel superior; those who struggle may feel condemned. The simplicity of grace becomes clouded by performance metrics.

Paul cautions against judging one another in matters of ordinances (Colossians 2:16). Mixing law and grace produces confusion, as Galatians demonstrates vividly. The Galatian believers were not abandoning Christ; they were adding legal requirements. Paul responded with urgent correction.

Financial obligation rooted in law can create the same dynamic. Joy diminishes. Guilt increases. Giving becomes transactional rather than relational.

Liberty and the Spirit’s Role

Second Corinthians 3:17 declares, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty.” Liberty is not license; it is freedom from compulsion.

Romans 8:2 speaks of “the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus” making believers free from “the law of sin and death.” The contrast between law and Spirit shapes Paul’s entire approach to Christian living.

Under grace, the Spirit leads believers in generosity without fixed quotas. Some may give more than ten percent. Others may give less during seasons of hardship. The measure is not uniform percentage but willing participation.

This liberty does not threaten ministry. It refines it.

Paul’s Own Financial Practices

Paul’s biography offers insight into his theology. In Acts 20:33–35, he reminds the Ephesian elders that he coveted no one’s silver or gold. At times, he supported himself through tentmaking to avoid burdening converts.

In 2 Corinthians 11:7–9, he recounts preaching the gospel “freely.” He accepted support when offered, but he refused to merchandise the message.

Conversely, he warns Timothy about teachers who suppose “gain is godliness” (1 Timothy 6:5). Titus 1:11 describes individuals who subvert households for “filthy lucre’s sake.”

Paul distinguishes between legitimate support for ministry and exploitative fundraising.

Supporting Ministry Without Legalism

None of this negates the financial needs of churches. Buildings require maintenance. Missionaries require support. Staff require compensation.

Paul affirms in 1 Corinthians 9 that those who preach the gospel have the right to live of the gospel. Yet he frames this right within voluntary generosity, not compulsory taxation.

When giving is presented as partnership rather than payment, believers participate joyfully. When it is enforced through threat or shame, trust erodes.

Healthy ministry thrives on transparency and doctrinal integrity.

Is “Scam” the Right Word?

Calling tithing a “scam” is provocative. In some contexts, the word may describe manipulative systems that exploit fear for financial gain. In others, it may unfairly malign sincere leaders who teach tithing out of tradition rather than malice.

The deeper issue is not motive but doctrine. If tithing is taught as mandatory for the Body of Christ, it requires explicit New Testament authority. Pauline epistles provide none.

The absence does not condemn generosity. It reframes it.

Conclusion

The debate over tithing is ultimately a debate over law and grace. Israel’s covenant included structured financial obligations tied to Temple worship and Levitical service. The Church, according to Paul, operates under a different dispensation—one defined by liberty.

Grace giving is voluntary, cheerful, and proportionate. It does not rely on fear of curse or promise of guaranteed return. It rests in the sufficiency of Christ’s finished work.

“Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free.”

If righteousness cannot come by the Law, as Galatians 2:21 declares, then neither can spiritual standing be measured by adherence to its financial codes.

Generosity remains biblical. Compulsory tithing for the Church, however, finds no command in Pauline doctrine.

The difference is not trivial. It is the difference between obligation and opportunity, between bondage and liberty, between demand and devotion.

In the end, the question is not whether believers should give. It is whether they will give under law—or under grace.